The final writer featured in our focus on lesbian/queer Australian women writers is Francesca Rendle-Short, a writer of essays, memoir and fiction. Her latest, critically acclaimed memoir-cum-novel Bite Your Tongue (Spinifex Press, 2011) was shortlisted for the 2012 Colin Roderick Literary Award. Her short fictions, photo-essays, exhibition works, reviews and poetry for the page and wall have been published in literary journals and magazines, online and in exhibitions. She is also an associate professor in creative writing at RMIT and co-director of WrICE and the nonfictionLab. In her rich piece below, Francesca writes about how rigid identities are tied to a lack of imagination; we must dream of other ways of being before we can inhabit them.

If you missed the other writers featured this month, click these links for posts by Inga Simpson, Tricia Dearborn and Lee Winter. If you’ve been inspired by these interesting, gentle, humorous and thought-provoking posts and you’d like to find more lesbian/queer Australian women writers, you can head to our list on our Diversity page.

Give Breath a Chance

I have a secret love of pineapples – spiky tops, sweet yellow flesh, the Fibonacci sequence impressed into the skins – pairs, threes, fives, eights or thirteens, but never fours. I love writing about them, or referring to them in my writing.

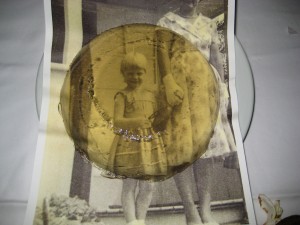

For most of my younger years I grew up in Queensland in the place a lot of people call Pineapple Country. I like collecting Pineapple Girls, like this one from 1864.

Just look at the shape and line this Pineapple Girl makes with her body and skirt, her fancy pineapple crown of hair, and something of a curl across the moon of her countenance … the way she emits light through the phosphorescence … gives breath a chance. (‘The Pineapple Girl’, Queensland Historical Atlas, Imagination, 2010)

Thinking about pineapples reminds me of my mother who is buried near Bli Bli on the Sunshine Coast in Brisbane, near the Big Pineapple. My mother hated me writing; she hated books.

Angel Rendle-Short was a morals campaigner, an agitator, a social rebel and protestor: anti-smut campaigner and well known for her views. She appointed herself as moral guardian to the children of Queensland. Over many years she railed against what she called permissive educationalists, teachers who promoted alternative lifestyles, sex education, the spread of venereal disease, moral corruption, homosexual marriage and lesbianism. People thought her mad. In the press and on radio she was called a crazy reactionary, irrational, a ratbag. She was a radical – but on the Right. Angel wanted to uphold the sanctity of the nuclear family, provide wholesome entertainment for the kiddies; she decried such perversions as homosexuality (‘I oppose the evils of homosexuality, sodomy…’ Semper Floreat, November 1975).

Angel put together lists of really good books she wanted to ban and to burn, books such as To Kill a Mockingbird, Catcher in the Rye, Lord of the Flies, The Well of Loneliness, Lolita, The Female Eunuch, Waiting for Godot and Gone with the Wind. She thought that if I read these books when I was young it would teach me to be a ‘permissive rebel’ (‘School textbooks slated’, Courier Mail, November 1975). I’ve written about this in Bite your tongue:

I look up the words permissive and rebel, wonder what one might look like.

Permissive meaning tolerant, liberal, especially in sexual matters, from the Latin permissio as in ‘permit’. And rebel meaning a person who fights or resists control and authority from the Latin rebellis or bellum as in ‘war’.

Permissive rebel. Permissio rebellis. Permit war.

I like the way these words look in the newspaper, the black and white print, how the typesetters spaced out the letters, horizontally and vertically, how the last letter e in permissive separates out from the rest — the way it accidentally drops below an imaginary bottom line as if it is being set free and riding away.

[…] I imagine my mother cutting out the words and sentences and sticking them into her scrapbook. (pp170–171)

In my family bodies didn’t exist – skin, tongue, touch – except as a site for rebellion and sin. Things of the body were only ever talked about in spiritual terms, from a distance, or with the protection of medical jargon. The body was trouble, it was thought, one thing always leading to another. For Angel, homosexuality was worse than anything: she told me homosexuals were better off at the bottom of the ocean with a chain around their necks. When she or my father used the word, they spat out the syllables: hom-o-sex-u-al with emphasis on sex. They never said the word lesbian out loud – it was that bad.

I came out to my parents suddenly when one day, unexpectedly, they said they wanted to fly down to visit me from Queensland; I was living in Canberra at the time. Before they arrived, I determined I had to tell them something (apprehensively it as to be said): that things had changed, that they needed to know something before they turned up, that I was living with a woman, that I was one of those L–s they hated so much. I wrote them a letter, agonising over every word. Needless to say they never visited, in fact they never came to visit me again.

In my family there wasn’t any such thing as change. There was constancy and steadfastness, everlasting. Any change of heart was only permissible if it was of the Jesus-change-of-heart variety. And my mother, true to her principles, stood by her beliefs to the very end – even if that meant rejecting her daughter in the last week of her life, which she did, even if that meant condemning her to the ocean floor with chains. My mother didn’t alter her views to her very last breath.

In her Daily Light that I found in the drawer of her bedside table after she died, a book of biblical precepts she read every day, I found a note she’d written in pencil across the top the day she heard the news that I was a lesbian, February 8: Francesca at war.

It’s funny how these coming out moments write themselves.

I didn’t reconcile with my mother before she died and I’m glad of that. It would have been false if she ‘turned’ in those last weeks. I’m glad I walked out on her when she told me she couldn’t love me. I’m glad my siblings, all five of them walked out with me in solidarity. I’m glad I didn’t go back into her palliative care room until she was quite dead, alabaster and cold. I’m glad I was thousands of miles away when she took her last breath. I’m glad my siblings called me back gently to be with them at her death-side.

I’m glad that I’ve said this too, in this writing, for being honest. Glad to be glad, if you like.

Who was it that said: What other people think of you is none of your business?

You can’t change the heart of an oppressor, but you can change your own heart.

Perhaps the sort of change I am talking about here is something of instar as the wonderful American nonfiction writer Rebecca Solnit describes the stage between moults: ‘something both celestial and ingrown, something heavenly and disastrous … oscillating between near and far’ (Field guide to getting lost, p.83).

I think I became interested in the idea of how change can move you to open up and embrace life and its imaginative possibilities because I grew up in a family where change was ruled by fear. Fear of getting it wrong and going to hell; fear at not recognising yourself and going to hell. Change: cam-bir-e to exchange, as a verb to transform, to make different from. Or change: to pass from one phase to another, to remove one’s clothes and put on different clothes – thinking here about bodies and identities and sexualities, appearances and realities.

Solnit thinks she became an historian because she didn’t have a history … she was interested in ‘telling the truth in a family in which the truth was an elusive entity’ (Field guide, p.58).

I think I became a writer because I came from a family that eschewed telling stories, that feared the imagination, that lived in a literal world, a black and white world, a fixed world where telling the truth – the so-called truth – was predicated on the dogmatic word of God.

I also think I became a writer because my mother hated books. Because I wanted to discover what could be so bad, what was there to fear. I wanted to look fear in the face, feel fear: write fear. I wanted to find out how to make these things that she hated so much, that she wanted to destroy.

I know now that the imaginary can change things, big and small. You can imagine different sorts of endings, different beginnings. You can alter your point of view; you don’t have to come to conclusions, you can be slow to judge or not judge at all.

The imaginary enlarges your world, gives you an education of the heart, as Susan Sontag would say.

You open up to loving in a way you’ve never loved before. Give breath a chance.

Footnote: I did an exhibition once, called Another book of breathing, where I put my mother and me into jelly and watched us go red with mould, still holding hands: from the Going to church series.

This post has been adapted from a keynote given recently at the Australian Lesbian Medical Association (ALMA) conference in Noosa, See Change, 5 September 2015: ‘Skin, Tongue and other Transgressions’

Images: ‘John Nicholson’s daughter with part of their pineapple crop at Grovely, Brisbane, Queensland, 1864’, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, image 189935; ‘Permissive rebel’, drawing by author, Bite your tongue (Spinifex Press), p.171; ‘Going to church’, Another book of breathing, And Is AAWP conference, University of Canberra 2007

How exciting to read this series and especially from QLD queer writers – I am old enough to remember your mother’s ( and other people’s) campaigns Francesca – feels like things are changing – I am bringing my film All About E to QLD for 3 screenings in Brisbane and one in Maroochydore in November, something I would never have imagined even possible – look out for them (see website for details http://www.girlsown.com/screenings/). Love to see readers there, Louise