Mary Theresa Vidal (1815-1873) writing as Mrs Francis Vidal

On Wednesday, Stacey Roberts discussed her use of the AWW archive to help with her Honours thesis. Today’s fiction selection, “Thomas and Anne Thompson”, is by one of the authors she’s researching, Mary Theresa Vidal. It’s the first in a series of morality tales by Vidal called “Tales for the Bush”.

On Wednesday, Stacey Roberts discussed her use of the AWW archive to help with her Honours thesis. Today’s fiction selection, “Thomas and Anne Thompson”, is by one of the authors she’s researching, Mary Theresa Vidal. It’s the first in a series of morality tales by Vidal called “Tales for the Bush”.

“Thomas and Anne Thompson”

“Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.”

Exodus, xx. 8.

CHAPTER I.

THOMAS and Anne Thompson were among those who determined to leave England for New South Wales. They had been married eight years; their family was increasing, and labor becoming scarcer and scarcer. They heard of other families emigrating and that they easily got high wages, and lived in plenty: so they thought with their four children they would do so also. They were both honest, hard working and strong people, and Anne had been well brought up by a careful and pious mother, who had lived many years as servant in the squire’s family. Anne was her only child, and she had been able to keep her at school, and, what is of far more consequence, she had set her a good example. Old Nurse Gordon, as she was still called, was well provided for by her former master’s family, and though it was near breaking her heart when she heard of their plans to emigrate, she could not find any reason against it. She laid down her spectacles on the old Bible from which she had been reading, and, wiping away the tear from her eye with the corner of her white apron, she patted her little grandchild’s head and answered, “well, Anne dear, I’m not learned enough to gainsay you, may be ‘tis just as you and Tom say; but, if it was God’s will, I should have wished to have you close my old eyes and see me laid in the grave – but His will be done!”

“Aye mother, that’s the way to look on it,” said Tom, “cheer up, and we’ll save you a little something in that country which will go to make you more comfortable.”

“Thank ye kindly, Tom,” said the old woman, “but I am, thank God, well cared for – while my missis lives, I shall never want – night and day I pray God to bless her and her’s – and you must do so too, for oh! it’s a cruel comfort to think that, though we’ve no silver nor gold, we have one way of repaying they that are kind – we can pray to God for them. And now,” continued she, “let’s have a cup of tea together,” and she and her daughter spread the tea-things and produced the loaf.

This was the last time they ever met in that little cottage. It was Sunday evening. The old woman wore her Sunday gown, and white apron; the meadows seen from the door looked green; the sun set very gloriously, and threw its slanting red beams on them as they sat: the roses and sweet briar smelt very sweetly and they heard the chimes of the village church; for in that place they chimed every Sunday evening. As they sat, feeling sorrowful and sad, the old mother again spoke, “I’m thinking that’s a sound ye’ll not hear yonder; I suppose there’s no church bells across the seas.”

“I suppose not,” said Tom, “it is a new country, a fine place for farming and grazing.”

“Well, I hope God will prosper you – but mind my last words – when I’m dead and buried, mind my words ‘honor the sabbath day, and keep it holy.’ When once we forget this, we don’t know where to stop: and Anne, my dear, see I give you this book, this Prayer Book; use it, and teach the children out of it; look, my name is on it – read it Tom.” Tom read – “this book was given to Anne Gordon by her mistress as a reward for her punctual attendance at church.”

“Yes,” said the old woman as she followed her son-in-law’s voice – “yes, that’s it – and now I give it to you, Anne Thompson, with my blessing; and you Tom, you have been a kind and sober husband to her; and now you are going so far, be sure you mind all your duty – may be there’ll be no good parson like Mr. Howe – but remember his words, and keep your church and fear God.”

It was now time for them to go, so putting the children’s hats and bonnets on, Thomas and Anne returned home; they had a walk of a quarter of a mile, but it was a pleasant evening and they talked cheerfully of the future; how they should save money and buy a farm, and, perhaps, grow rich.

CHAPTER II.

In five months from this time the family of the Thompsons reached Sydney. They had encountered some troubles on the voyage: Anne was very sick, and it made her very weak and inclined to be discontented and cross tempered, and there were many discomforts on board the ship. There were a great many passengers, and some of the bad ones quarrelled; but Tom was steady and sober, which was a great comfort. He attended to the children when Anne was ill, and was always ready to lend a helping hand when it was wanted, so that he became a favorite.

Their little boy John, the eldest, got very ill, so ill, that they began to fear it might be their lot to bury him in the ocean, as one other poor mother had done her child. This was a sore trouble to Anne; she thought she could have borne to bury her child under a green sod; but to hear the coffin plash down into the waves of the deep sea – that was dreadful.

While she was thinking in this way, her mother’s gift came into her head, and she opened the Prayer Book. She turned to the burial service; there she saw that the same good and holy words would be used as if she were at home in Ringford church yard; and at the bottom of the service she saw that there was something written expressly for a sea burial; it spoke of the sea giving up the dead and of God’s subduing all things to Himself.

Now this comforted Anne, and she felt what a blessed book the Prayer Book was; there were prayers for every thing; in sickness, in death, or in joy. Whether on dry land, or on the deep waters, turn to your Prayer Book, and you will find words of comfort and instruction; the self same words too which all good Christians have ever used, the same words which are uttered in every church throughout the world. Thinking of these things and watching by little John, was of use to Anne; she felt she had been impatient and fretful at the discomforts of board-ship, and as she sat by the sick child, she prayed for forgiveness and for grace to help her to quench such feelings in future. Thus the trial was turned into a blessing, and Anne felt every day more ready to submit cheerfully to God’s will. But it pleased the Almighty to spare them the trial of losing their child. Little John recovered; and before they reached land, he was as rosy as before, and said his catechism every Sunday, out of the Prayer Book, to his mother.

CHAPTER III.

I cannot tell you all that happened to them, or how many plans they had when they first landed; but they at last set up a little shop in some of the outskirts of Sydney; and besides this, Tom was able to get plenty of work at his trade, which was gardening. Every thing seemed to go on well: they had plenty of custom, and Anne’s tidy appearance and respectful manner brought people to the shop.

There was no church where they lived, but the service was performed in the school room, every Sunday; and the two eldest children went to the school. The custom of the place was for all these little shops, like the Thompson’s, to be kept open during Sunday. The shutters were half closed; and many persons bought all they wanted on Sundays, instead of coming on Saturday afternoon. At first this struck Anne’s conscience; she thought of locking up the house, and going to church at the school house, with all the children; but her husband objected, and said that would never do, they must do as others did – it was the custom of the country; and, if they refused to serve customers on a Sunday, they should have none.

“And that’s true, sure enough,” sighed Anne – “there’s Mrs. Harris over the way, and the Browns, and scores of others that make no more account of the Sabbath than if it was a common day; but its hard to be forced to serve and slave on a day of rest.”

“Never mind Anne,” said her husband – “its only for a time, let us make haste and save some money, and then we can do as we like, we can keep Sunday as we did at home, and you shall be quite a lady.”

Anne smiled, for she wondered what sort of lady she’d make; and then she washed the children’s faces, and tied their pinafores, and led them out to the door.

“Now go on steady there’s my dears, and behave well in church, and mind the text Johnny.” Then she turned into the little room which formed both kitchen and shop. She took out her book intending to read, but presently Mrs. Harris over the way stepped in, and Anne had to serve her with tea and sugar; some spice was wanted which could not be found without more light, so she went to open the shutter.

Just then, Mr. Martin, the clergyman passed: Mrs. Martin and their three children were with him. Anne dropped a curt’sy, for she had not left off that custom which some people think unnecessary after they leave England. Her good mother had always taught her to be respectful to her superiors, and that politeness to one another is taught in the Bible. So Anne curtsied – but how ashamed she felt. She fancied Mr. Martin looked sternly at her – she thought that Mrs. Martin stared at her dirty apron.

“Ah,” thought she, “it used not to be so on a Sabbath morning at home, but it is just like no Sunday here, no bells, no church, no any thing.”

“What are you so long about taking down the shutters,” called her husband: so Anne hastily put down the shutter, and went in; but her heart was ill at ease – she did not feel happy.

Next Sunday, however, she minded it less; she did not see Mr. Martin pass. Mrs. Harris and Mrs. White came and laid out upwards of a pound between them, for Mrs. Harris was expecting some friends from Sydney to tea. They talked of the new store further on the road, where very cheap and good things were to be had; “but they will not do,” said Mrs. Harris, “they shut up on a Sunday because she’s a Methodist. Such nonsense, expecting people to lose Saturday, which is always a busy evening, because they won’t weigh out a penny-worth on Sunday; besides, really, in this country, folk hav’nt the convenience for keeping things, and it is very hard not to enjoy a good dinner on a Sunday.”

“Well Anne,” said her husband that evening, “this good day; we’ll put up the money to buy a cow – I saw a beauty the other day – when we’ve got two or three head, then I shall think we are fairly in for good fortune.”

CHATPER IV.

SUNDAY after Sunday passed; weeks and months came and went; all prospered with the Thompsons. They had bought a cow and calf, and put it out to a run; they lived well and put by a little besides; still, neither of them looked so nice or so cheerful as when they lived hard at Ringford.

Anne’s clothes got out of repair; she never had any time to mend them; she was in the shop every day. They had plenty of custom, and all her time was occupied. She worked hard, and now she did not look forward to any day of rest. There was no quiet Sunday when cares and troubles were forgotten; no regular attending church, but only now and then when she could persuade Tom to mind the shop. There was no quiet evening walk; no hearing the children read. They had meat, and bread and butter, and plenty of tea and sugar, it is true, besides many other little luxuries; but it was eating in discomfort; there was no regular time for any thing. All days were alike; no Sunday came to mark the time – to being another week with the minister’s blessing, after a grateful rest to the mind and body.

Anne was not happy, but she did not perhaps put it down to the right cause. Her conscience had spoken, and had not been heeded, and now it did not prick her. We soon slip down a hill when we once begin.

CHAPTER V.

ONE day, about this time, Mr. Martin came into the shop. After asking a few questions about her children and husband, he said, “How is it I do not see you at church Mrs. Thompson?” “Why sir, I do go whenever I can.” “Very seldom I fear,” answered Mr. Martin, “it is but too much the custom in this country to neglect church, and I am sorry to see that, amongst others, your shop is not shut on a Sunday; surely you know this is breaking the fourth commandment?” “I know it sir, I know it is very wrong,” and Anne burst into tears, “but what are we to do? people will buy on a Sunday, and we depend on the shop.”

“It may be a trial, my good woman; but if a few decent people held out, refusing to serve, any one on a Sunday, taking care to be doubly attentive and careful on other days, I do not think they would really lose. Besides, suppose they did lose – suppose, at the year’s end, they were so many shillings or even pounds the poorer, they would still have gained.” ‘Better is little with the fear of the Lord, than great treasure,’ &c. – “It is positively and openly breaking God’s commandments, and you cannot expect His blessing. Besides the evil it is to yourself, it is setting a bad example, and we are all answerable for this.”

“Oh, it is not the likes of us people would take example from,” said Anne; “though I know it is a sin in us – I always said so.” And she cried again.

“Well, but if you really think that it is wrong, do not do it. Begin at once; it may be hard, but pray humbly that God will help you, and you will be able to resist the temptation. I am sure you have been taught your duty: your manners and appearance, and that of your children, told me at once that you had been taught. Surely you did not keep Sunday thus at home?”

“Oh la! no, sir – God forbid! But oh, that was all different; every body went to church, and bought things on Saturday; and the bells rung, and seemed to tell us it was Sunday. Oh, I wish we were back again!”

“There are not bells, it is true,” said Mr. Martin. “In this new country much is wanting that we are used to at home; but it only makes it the more necessary that each be more careful of himself, and pay even greater respect to the Sabbath. We can all, even the poorer, contribute to this. We can all observe the Sabbath, and try to pray in church, as God commanded; and many can lay by out of the store which God gives them, to help towards erecting real churches, and having bells. But I will call again; I see a customer waiting. Good morning.”

“Good morning sir, and thank you,” said Anne, and, after serving the young woman who had just come in, she thought over all Mr. Martin had said. She felt it was all true, every word; her old mother’s words too came back, and going into her little bedroom, she knelt down and begged God to forgive her and help her to be better. She found it was not so easy to pray as it used to be; she had forgotten the prayers. Ever since Sunday had not been regularly kept, she had become less regular n her own daily prayers. She left it to chance; when she thought she had time she said a prayer; but very often she passed the day without. Now, she could only remember the Lord’s prayer, but she repeated it several times, and then she began to resolve to keep Sunday. But the great difficulty lay in persuading her husband. However, he was very kind to her and always seemed to take her opinion, so she determined to try and not be discouraged.

Accordingly, that evening, when Tom was making up his accounts, and seemed pleased at finding a good round sum was coming to him, he said, “Come Anne, what’s the matter? I declare you’re as blank as November – you shall have a new bonnet by Christmas as I’m alive; and we’ll have roast beef and a bottle of Ale, and I wish old mother was just here to share.”

“Oh Tom, that word is a dagger to me; poor mother what would she say to see us so? don’t you think, Tom, that now we could do without serving customers on the Sunday?”

“Why I thought you’d as good as forgotten that;” said Tom, “you know we do more business Sunday morning than any other day in the week.”

Anne then repeated all that Mr. Martin had said, and added “She was sure that, though they were richer, they had not been happier; and that they both felt weary and worn out on a Monday morning, instead of rested as they used to be at home: Besides,” added she, “I’m willing to try and make good the loss; I can take in a bit of washing; I can do clear starching as poor mother shewed me, and can make a penny by it.”

“Well, well, do it if you like, but see if we don’t lose our custom; but do as you will.”

CHAPTER VI.

THE next day Anne told every one who came to the shop that she intended to take in clear starching; and when Saturday night came she began to feel rather nervous and ridgetty. She put away all she could; hid the scales and weights, and removed as much as she could out of sight.

Tom looked on at these preparations rather gloomily; but Anne took courage and went on. She took out their Sunday clothes all in readiness as she used to do, and though tired when she went to bed late that night she felt lighter at heart than she had for some time. But when we have allowed ourselves to do wrong for any time, we must not expect that it will be easy and smooth for us to alter just when we please. It will be hard at first, nor shall we feel always that peace which the consciousness of doing right is expected to bring. This is our punishment, and we should receive it humbly.

The next morning Anne shut the door, and dressed herself and children for church. Soon came a dirty ragged little girl for a pound of candles. “The shop is not open to day my dear,” said Anne quite boldly; and she could not help feeling how much better it was to have one’s children clean and neat as her own were.

So far it was well, and little Johnny sat down and began saying over the commandments which he was learning for school.

Then came a knock at the door. “See who it is Tom,” said Anne, who was in the bed-room tying on her bonnet. “It’s Mrs. Harris, that’s who ‘tis better not offend her mind – she’s out and out our best customer; always pays regular, and has long bills.” Anne fidgeted at her bonnet strings. “Oh dear, dear, what shall I do, there she’s knocking again, do speak to her, Tom.” “Mrs. Thompson,” called Mrs. Harris, “are you in?” “Yes,” said Ann, stepping forward, “but, but –” “Why were are you going, hey? come, be quick, I want a lot of things to-day.”

Tom went into the bed-room; he had promised Anne she should do as she liked; but he could not stand this.

“We have determined to shut up shop Sundays,” said Anne timidly, “I was just going to church.”

“To church! shut up shop! you astonish me! are you mad, woman? do you mean to lose all your business, just because you want to be my lady?”

“No,” said Anne, “not to be a lady, but to go to church.”

“Hoity toity, heard I ever the like;” and Mrs. Harris laughed loud and rudely; she looked red and angry too.

“Well, Mrs. Thompson, as you like; but I’m not going to be insulted: if you choose to refuse to serve me, you know what you lose. I consider I’ve been a pretty good customer, and this is what I call downright uncivil.”

Here Tom put out his head, and with an expressive gesture, intimated his wishes to Anne.

Poor Anne! she stood in perplexity. It was a dear loss indeed if Mrs. Harris left them; her resolution began to waver; she was going on towards the counter, when, as she passed her children as they sat on the bench, she heard John saying to himself, “Remember that thou keep holy the sabbath day, &c.” Then, quick as lightning came back her old mother’s words; she could almost fancy she saw her standing before her. Had Anne refused to listen to her conscience then, it is awful to think what might have been the consequence; but she did listen: her little boy’s voice, “Remember the sabbath day,” rang in her ears; she stopped. “I’m very sorry, I hope you’ll not take it ill in me, Mrs. Harris, but I cannot serve on Sundays any more.”

The effort of saying this brought the colour into Anne’s face – Mrs. Harris flounced out of the shop – Tom swore that her cursed nonsense had ruined them – and poor Anne sank on the bench in a flood of tears. Tom refused to go to church, so she set off very sorrowfully with the children. Mr. Martin was not there, so she had not even the comfort of feeling that he would observe she had minded his advice. The day was spent sadly, and Anne felt that it is far more difficult to climb up the hill again, after slipping down, than to go on steadily every day.

CHAPTER VII.

The following week, Anne secretly hoped, would bring Mr. Martin; she felt it would be a comfort; but he did not come, and she had a great deal to bear from the remarks made by idle gossiping persons; for Mrs. Harris had taken care to spread the story, and every one wanted to know about it. Some turned up their noses and talked of hypocrisy, and trying to appear better than other folks, and some said it was only just laziness, that she might take holiday on Sunday.

Tom still seemed annoyed, and one day after meeting Mrs. Harris coming out of another store, and being abused by her in no measured terms, he said he could stand it no longer and they must leave the place; he had no idea of being laughed at or pointed at.

Poor Anne! all this was very trying, and she almost felt inclined to give up the point, but just then she caught sight of the Prayer Book as it lay on the shelf, and that brought in thoughts which drove the others out. As far as she could reckon up there would be a great loss this week; so she determined to go and apply to Mrs. Jenkins for fine washing. Her application was successful; she had a few things to try how she could do it, and she was obliged to rise earlier in the morning in order to get them done.

When Saturday evening came she put on her bonnet, and went round to some of the neighbours and asked if they should be wanting tea, sugar, or candies, as, if they did, she would weigh it out, and send it down, for the shop would be shut on Sunday. One or two said if it was shut on Sunday they could go elsewhere, but others said they should be much obliged for her to send it down that evening: and the parcels came so neatly tied, and such good weight, that they declared after all Anne Thompson was a decent little woman, and civil and honest; and they did’nt care if they had got all in before Sunday – it was more comfortable like – and then when they found they had not to go to the shop, they had more time on the Sunday, and nothing to think of, and some of them went to church.

This Sunday no one came but some strange man, to the shop, and Anne’s earnings by her washing nearly made up the loss of the other Sunday customers; so Tom was in a better humour, and went with her to church.

Mr. Martin was there, and preached on the duty of keeping the sabbath. Anne and Tom both listened eagerly.

When he summed up the vices, and consequences that usually attended sabbath breaking, Anne trembled. She joined heartily in the prayer after the sermon, “That the words she had heard that day might bring forth in her the fruit of good living,’ &c.

CHAPTER VIII.

ANNE and her husband were now very regular attendants at church. Christmas came, Anne had not her new bonnet. They were not so rich as they might have been, had Mrs. Harris and the others continued to deal with them; but the little cottage looked cleaner, and more comfortable: they had their baked beef for dinner; and as they took a stroll in the evening together they both acknowledged that it was well to have one day in seven to rest, and to be able to read the Bible, and hear good things in church. “The thoughts last out the week,” said Anne. “Yes, I often think of them when I’m digging,” said Tom: “The other day, when I was pruning Mr. Short’s vines, I minded what the parson said about the vine on Sunday that as we pruned the plants there was finer fruit, so it was with us – we must prune ourselves, and cut away all that grows out wildly like.”

As they were talking, a man came up, and asked if they were called Thompson, and, on being informed they were, he said he supposed this letter was for them, he had just arrived from England, and had brought it from Mr. King of Ringford. “Ah that’s our clerk, and that’s from mother,” said Anne.

The letter was written by the clerk; it was to tell them that good nurse Gordon had quietly and peacefully breathed her last; that she sent them her last blessing, and left them her Bible, and what little clothes she possessed.

Upon comparing notes, Anne found that her mother had died on the very day on which Mr. Martin called, and spoke to her about shutting up the shop on a Sunday. She felt very glad she had by God’s grace profited by the visit. She looked upon it as an especial warning of a watchful Providence, and she never afterwards felt tempted to break the Fourth Commandment.

This performing one duty helped her on to many others. Going to church opened her mind to other faults, and it brought a blessing which the world and its riches could neither give nor take away.

They had trials and disappointments, but they knew from whom they came; and Tom and Anne lived to see their children turn out well. No cottage so clean and neat as the Thompsons, with its gay little flower border before it. The shop continued to support them, and they put into the plate at church every week something towards a real church, and, as Anne hoped, a peal of bells.

Mr. Martin had often called, and proved a good friend to them. One day when he was observing how much more comfortable and tidy every thing was about them than in the other cottages, and how much more leisure they seemed to have; Anne colored up and said “Ah sir, it is you, next to God and my poor mother, we’ve to thank. It is all owing to keeping the Sabbath day.”

Readers go and do likewise.

~

Mary Theresa Vidal, writing as “Mrs Francis Vidal”

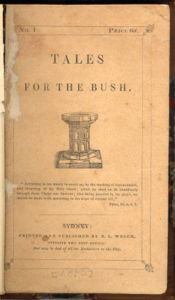

Tales for the Bush

Text taken from Tales For the Bush (1845), digitised by University of Sydney (1997), and available to be read online (use the > keys) or for download here.

Vidal’s lists of publications can be found on our AWW archive pages for the 1850s and 1860s.

I’m afraid the moral was quite wasted on me, I enjoy working Sundays and taking my days off during the week.

Good though to be reminded what a tremendous break with family it was to emigrate, especially as the Thompson’s don’t seem to have written.

How rigid they were (and superstitious)! The underlying principle, though, of having at least one day of rest a week seems reasonable. As for the break from “home”, yes, that must have taken a lot of courage, and doubly hard for the illiterate.

That’s true: even one day off a week has become a luxury for so many workers. There has been legislation passed in Ontario, Canada this year, which restricts employers from requiring evening and weekend availability for full-time workers, but of course that only means some will continue to feel that they must, despite the rules.