by Bill Holloway

Ernestine Hill (1899-1972) was a journalist, author, single mother and an intrepid traveller. Her son, Robert’s, father was probably media mogul, RC Packer (grandfather of Kerry) for whom Hill worked in the 1920s at Smiths Weekly, and then, at Associated Newspapers’ the Sydney Sun.

Ernestine Hill (1899-1972) was a journalist, author, single mother and an intrepid traveller. Her son, Robert’s, father was probably media mogul, RC Packer (grandfather of Kerry) for whom Hill worked in the 1920s at Smiths Weekly, and then, at Associated Newspapers’ the Sydney Sun.

The Great Australian Loneliness (1937) is …

… the story of a journalist’s journey round and across Australia, far from the rhythm of the ‘big machine’ and the sameness of cities…

It was in July, 1930, that I first set out, a wandering ‘copy boy’ with swag and typewriter, to find what lay beyond the railway lines. Across the painted deserts and the pearling seas, by aeroplane and camel and coastal ship, by truck and lugger and packhorse team and private yacht, the trail has led me on across five years and 50,000 miles, a trail of infinite surprises.

(Author’s Foreword)

I have written many times that Hill begins her journey at Hamelin Pool/Shark Bay on the west coast and ends up years later riding a camel into Alice Springs – which journey Robyn Davidson mirror images three decades later (Tracks), riding her own camels 2000 km across the desert from Alice to Hamelin Pool. But I see now Hill’s journey in fact starts in Perth, and it takes her a flight to Carnarvon and a coastal steamer to get to Shark Bay, a town so isolated that its only connection with the outside world is the WA government-owned Koolinda “that once in a month anchors seven miles off-shore.”

I love connections, and during these years this coastal service in the Koolinda brought KS Prichard home from Onslow after she was at Turee Creek (100s of km inland of Carnarvon) writing Coonardoo; and brought the Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence girls south under police detention for the crime of being mixed race.

I love connections, and during these years this coastal service in the Koolinda brought KS Prichard home from Onslow after she was at Turee Creek (100s of km inland of Carnarvon) writing Coonardoo; and brought the Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence girls south under police detention for the crime of being mixed race.

In every town and settlement, Hill finds “characters’ whose strange stories and wanderings she summarizes, and then she throws in landscape and history. Flying north again, to Roebourne, she writes:

From the coast southward for a thousand miles, across the famous old goldfields of the Pilbara, stretches the great desert of spinifex and gold, with scores of towns forsaken, some of them with an ancient mariner of a prospector alone to tell the story of the mad, glad days of yore. Warrawoona and Cue and Nullagine, Bamboo Creek and Menzies and Lawlers and Nannine, to-day they stand for poppet-heads stark in the wilderness, sixty-head batteries buried in the sand, and a couple of hundred empty houses and stores and hotels, the haunts of owls and bandicoots.

I work in the North-West, delivering machinery to new iron ore mines and indeed to some of these old gold mines now revived. The picture Hill draws is still familiar 90 odd years later. Nannine for instance, once wildly prosperous, now just a deserted cemetery and scraps of rusty iron in the desert.

The difficulty with this book is Hill’s attitude to the Aboriginal people she meets and to Aboriginal people generally. For her times it is undoubtedly sympathetic. For instance, she is the first writer I read who discusses Aboriginal ’employment’ as slavery. Though some earlier women – no guys I ever read – at least hinted at the fact that ‘native’ stockmen and house servants were given only food and scraps of clothing for their troubles, and ‘permission’ to sleep outside on their own land.

Hill believed – along with Daisy Bates, whom she meets later in the book, and indeed with most white Australians up until at least the 1950s – that the Aboriginal race was dying out. This belief may only be achieved by counting mixed-race people as non-Aboriginal, when the great majority of them were being brought up by Aboriginal parents – at least until they were stolen away by the government.

From Roebourne, Hill writes of the pearling industry at nearby Cossack in the 1880s –

Nearly all of the pearlers employed aboriginal [sic] divers, for … native labour was free, too free. A bag of flour and a stick of tobacco bought a human life… From hundreds of miles inland the blacks were brought, men who had never seen the sea and now were to live and die in it. A dark sentence of history tells that when they refused to come voluntarily they were lassooed from horse-back, and dragged… With a clumsy cross the natives signed their death-warrants. Few of them lived longer than two years.

She talks to old prospectors, records their yarns, moves on. Port Hedland. Broome. She never once mentions her son, but according to other sources he was with her at various times, in the care of Hill’s Aunt Kitty, and at Broome they spent Christmas together.

From Port Hedland she takes a detour in the little train 114 miles out to Marble Bar: “under the big tanks at the Shaw River at noon the engine-driver boils up a billy of tea for all aboard”. I have an idea those tanks are still there. And at Marble Bar she hears of “Maudie and Nellie” the two little rabbit-Proof Fence girls who found their way home “across 1,500 miles of unknown desert” – about half that distance really, but why spoil a good story.

She is fascinated by the polyglot nature of Broome, where at the pictures announcements are made in English, Chinese, Japanese and Arabic; though, from her stories, many of the workers are Malay or Indigenous. One couple “when I last met them, .. had a dear little Cingalese-Japanese-Chinese-black-white son, who will be quite at home in Darwin.”

And so we go on, by plane and truck. to all the settlements across the Kimberley, to Derby, Wyndham, Fitzroy Crossing and Halls Creek, chatting all the way with old miners and cattlemen and sometimes – there weren’t many – their wives and widows; oblivious to the region’s terrible history of whole populations of Aboriginal people massacred, first reported in the 1905 WA Royal Commission “on the Condition of the Natives” (and the subject of Chris Owen’s Every Mother’s Son is Guilty (2016))

Hill’s nod to this history is –

The blacks were fairly ferocious up this way thirty years ago, but they are a genial lot now. Half of the white population died at their hands in the very early days. Great lusty fellows, they knew no white man’s law … To some of the first white colonists, particularly the multitude of the gold rush, they were just niggers, the boys shot at sight, the women used brutally. It led to complications, and the innocent suffered for the guilty on both sides.

You’ve got to love that “both sides”, no wonder she ended up an ABC commissioner.

I’m a Western Australian, so this a Western Australian review. Hill goes on into the Northern Territory and thence to North Queensland, chronicling White and Black characters alike. The saddest aspect of this is the false assumptions about race which were clearly widely accepted.

The overwhelming problem of the North-west and North of Australia at the moment is the steadily increasing propagation of the half-breed races… Child of a tragedy far too deep for glib preaching, half-way between the Stone Age and the twentieth century, his limited intellect and the dominant primitive instincts of his mother’s race allow him to go thus far and no further.

Eventually she makes her way back to Perth, then catches the Trans-Australian train to meet up with Daisy Bates at Ooldea siding. That’s a story worth an essay on its own. The last chapters of the book take us north, to Coober Pedy, Birdsville, Oodnadatta, over the SA-NT border to Finke Siding and, for a week via the last ‘camel mail’ in Australia, a camel train to Hermannsburg Mission, and so, a short hop to Alice Springs.

Australia’s largely urban population were fascinated by the Outback. At the turn of the century their information was coming mostly from fiction – Rolf Boldrewood, the Sydney Bulletin, Henry Lawson, Joseph Furphy, and countless novelists and short story writers, men and women, in all the newspapers.

To the best of my knowledge (write to me if I’m wrong!) Hill was at the forefront of a new trend of non-fiction writing. She is here travelling and recording from 1930 to 1935, published. in England, in 1937 though not widely available in Australia until 1940. Her two male counterparts – and all three were tremendously popular – were Ion Idriess who produced more than a book a year from 1931 onwards, starting with Lasseter’s Last Ride; and Frank Clune, whose output from 1933-on included countless books and magazine articles of Australiana.

The Great Australian Loneliness is still a book worth reading in the 21st Century. Hill is a notable role model for the Independent Woman. But you need to be aware of the terrible history of white settlers occupying Aboriginal land and ‘dispersing’ the Indigenous population, which she was clearly aware of but chooses, mostly, to gloss over.

.

Ernestine Hill

The Great Australian Loneliness

first pub. London 1937

340pp

First Australian edition, 1940

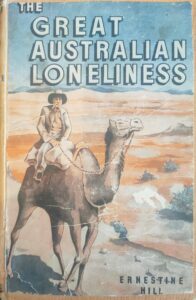

Cover pictured: My own ‘First Australian Edition’, fourth reprint, Robertson and Mullens Ltd, 1945

See also my review of Hill’s fictionalised biography, Call of the Outback by Marianne van Velzen

Bill Holloway, the author of this review, blogs at The Australian Legend. He is an old white guy the subject of whose (very) mature age M.Litt thesis was ‘The Independent Woman in Australian Literature’.

Greatly enjoyed this Bill, and your even-handed assessment of what she offers modern readers. I also like your suggestion re new style of nonfiction writing, though I can’t really comment not having read this. I was aware of her and Idriess in the 60s, less so of McClune though I knew his name.

I’m amused by the reference to “the sameness of cities” as Lisa and I have just discussed this briefly on my blog. I can understand the desire to get away from them. They can be differentiated of course but the difference can feel superficial.

I’m glad you liked it. Even before Hill, Idriess, and Clune I think the most popular Australian works were realsitic or semi-realisitic accounts of bush life – We of the Never Never, My Brilliant Career, all of Steele Rudd – but those three actively sought out stories, rather than lived and wrote them, and it probably earned them 2 or 3 decades of popularity.

Frank Clune I think most people, including me, know because of Dig, the story of Bourke & Wills. But as reinforcement my father gave me his Flight to Formosa in 1967. It’s relentlessly anti-communist and I’m not sure I ever read all the way through.

(I wonder what “most people” means these days, most people over 70?)

I prefer my fiction to have a good sense of place. Ian Rankin and Edinburgh for example. But like Hill, I also prefer not to be in them (cities). Except maybe for a couple of hours with good company on a Friday night.

That’s a title that would make me look twice. And I think the earlier statements are even more disturbing, than the final one you reference, in her assessment of the balance of power between Indigenous peoples and settlers, The use of the word “lusty” too. And the limp selection of the word “complications”. Interesting, too, that she views the timeframe within only a thirty-year context; it’s a useful device, to only focus on a timeframe that appears to support one’s limited analysis.

Buried in Print, of course the book is going to be problematic today, but as the review acknowledges, she is comparatively enlightened for her times- I find her writing a bit flowery to be enjoyable but again that was of her times.

“Lusty” meant full of health and vigour when she wrote it. Also the 30 years thing is an unfair judgement, she was writing a novel to entertain for $ not attempting an analysis -she wasn’t an academic by any stretch of the imagination.Thirty years prior to when she was writing the first encounters white people were having with Aboriginals in remote areas of Australia were occurring-so I don’t know how, she a white woman, writing of her subjective experiences could comment further back than that, I suspect that 30 years ago really means prior to/at the beginning of white people coming onto their lands.

I expect that common place attitudes today will be found to be problematic in another 90 years.