by Mrs Campbell Praed (1851-1935)

by Mrs Campbell Praed (1851-1935)

There is a great lake in one of the inland districts of Northern Australia. It is closed in by green ranges, which slope down to a beach of silvery sand. It has no outlet for its waters, which are salt as the sea. Pelicans and wild swans haunt its shores, and myriads of sea gulls and marine birds hover upon its calm surface. The lake is almost always still, for it is very shallow and in seasons of great drought its waters dry up altogether, and there is only to be seen a vast basin of shining sand.

But this does not happen once in a great many years. At most times it has the appearance of an untroubled sea, for it is not possible to see from one side across to its furthermost shore. Tiny wavelets sparkle in the daylight as far as the eye can reach. The moon rises from its waters, and the sun goes down beneath them in a glory of pink and gold, and the horizon clouds take strange shapes which make them seem like the gates of some enchanted city, or the trees in a dream garden.

Little Janie Galvin used to have all kinds of fancies about the lake and the distant invisible shore. She was an odd imaginative child, and would remain on the beach sometimes for hours together, dreaming her child-dreams, and keeping so still that the pelicans and ibises would come quite close to her, and the sea-gulls would swoop down and circle round her and her sickly little brother who lay sleeping in the warm sand at her feet; and they would perch on the rocks near her, and would flap their wings and utter their strange discordant cries, till she could almost fancy they had a story to tell her, or a message to give from that land over the sea – for the lake was the sea to Janie; she could imagine no ocean vaster.

The sea-gulls made her think of the wild swans of Hans Andersen’s story – the mistress on the station where her father was employed had sent her Hans Andersen one Christmas time, and she had a notion that they wanted to take her and little Dick to the opposite shore, and that there she should find Death’s Garden, where God the Great Gardener gathers His flower-angels, and that there her own mother who was dead would come and meet them, and would take little Dick in her arms, and would lead Janie by the hand – and so they would wander about together in the beautiful garden, and there would be no more harsh words or cruel blows; no more frightened quiverings of little Dick’s feeble body, no more sobbings to sleep after unjust punishment, no more lonely longing for the love which these two poor little children had lost when their mother left them.

The sea-gulls made her think of the wild swans of Hans Andersen’s story – the mistress on the station where her father was employed had sent her Hans Andersen one Christmas time, and she had a notion that they wanted to take her and little Dick to the opposite shore, and that there she should find Death’s Garden, where God the Great Gardener gathers His flower-angels, and that there her own mother who was dead would come and meet them, and would take little Dick in her arms, and would lead Janie by the hand – and so they would wander about together in the beautiful garden, and there would be no more harsh words or cruel blows; no more frightened quiverings of little Dick’s feeble body, no more sobbings to sleep after unjust punishment, no more lonely longing for the love which these two poor little children had lost when their mother left them.

Janie remembered her mother well, but Dick was only a tiny baby when she died. It was to Janie that the mother had given the little boy, and almost her last words had been, “Remember, darling, to take care of baby; don’t let any one be unkind to baby.”

Perhaps the poor mother had been thinking then of what did happen a little later when Joe Galvin brought home a stepmother to his children. It was quite natural that he should marry again. What could a stockman do with two motherless mites on an out-station thirty miles from the nearest women-folk? And then his duty obliged him to be away from the hut often for days and nights together, when it was mustering time and the cattle had to be brought from round the lake. But it was a pity he should have married Polly Warren, who was violent, intemperate, rough of speech, and hated sickly children.

Poor little Dick had a tendency to water on the brain, and he was often stupid and drowsy, and slow in answering his stepmother when she called him, and in obeying her commands. She said he was obstinate and disobedient, whereas the child was only dazed and frightened. Once she had beaten him severely, and Dick had been ill for days afterwards; and Janie, remembering her mother’s dying words, had vowed to herself that with her own little body she would defend her baby-brother from being a second time so cruelly treated. A stray blow now and then, a box on the ears, or an angry push were ordinary occurrences and not so greatly to be minded, but to see Dick tied up to a rail of the stockyard and beaten like a dog with the stockman’s heavy whip was more than Janie could endure. And now this was threatened again. Dick had been naughty. The stockman was away, and Polly Galvin had declared that on the morrow Dick should be taught by the lash which was master, he or she. In vain Janie had pleaded, had urged Dick’s delicacy and the possible consequences to his feeble brain. In vain had she entreated that she herself might bear the punishment. Polly was inexorable. The boy had disobeyed her: he should be sent to bed on bread and water at sundown. To-night she did not choose to tire her arms further after her day’s washing; and besides there was grog in the house, and Polly wished to enjoy her evening glass undisturbed. On the morrow she would be fresh for her brutal work, and she had something of the true tyrant’s pleasure in keeping her victim trembling in suspense.

Poor little Dick did indeed tremble and cry all that long evening, and Janie heard him through the slab walls of the verandah-room where he was locked up, and where she was not allowed to go to him. Janie’s own small frame quivered and shook in helpless misery and indignation.

What had she and Dick done that they should be used so? Why did not God have pity on them? And oh! If their own mother could look down from Heaven and see what they were suffering, why did she not come and help them?

All kinds of wild fancies and despairing resolves passed through Janie’s brain. If she could only get Dick away – if she could only hide him safe till her father came home! Surely, for her dead mother’s sake her father would prevent Polly from beating the boy.

He did not know – he could not know – how hard she struck; what her temper was when it was roused, and how she hated little white-faced sickly Dick. Janie had heard her say that she wished him dead. Perhaps on the morrow she meant to kill him. All Janie’s soul went out in passionate yearning for help. She prayed to God. She prayed to her mother, and while she prayed sleep fell on her, and she dreamed that the help had come.

It seemed to her that she and Dick were on the sea-shore, and the sea-gulls were gathered round them, and the birds’ great white wings were like those of angels closing them in from harm. Somehow the sea-gulls were not sea-gulls, but angels indeed with kind faces, and one had the face of her mother. The mother-wings folded round the two children, and seemed to lift them up in air, and Janie heard the dear voice say, “My poor babies! Mother will take care of you.” Then she awoke, and the moon’s rays streamed into the room, and for a minute or two Janie fancied that those white wings were still enfolding her. But it was only the white curtains of her little bed that flapped in the night breeze. The wind had risen, and outside on the lake shore she could hear the waves rising and falling, and the curlews in the bush were making their plaintive moan. Janie got up and dressed. The house was quite still, and she crept out along the verandah to Dick’s door and listened. Through the chink she could see Dick’s white face with the moon’s rays upon it, as he lay all dressed upon a sack on the floor; and she could hear the frightened gasps which seems drawn up from his heart out of very fear.

“Dickie,” Janie whispered softly, “don’t cry; don’t call out. I’m coming to you somehow. I’m going to take you where she can’t hurt you. Mother knows; mother will look after us.”

The child stirred uneasily; he was only half asleep. “Janie,” he muttered, “I’m so frightened, Janie. Can’t you come?”

Janie stole back to the sitting room. Polly was sleeping heavily. Down by the fire-place in a camp-oven was some new-baked bread, and Janie lifted the lid and broke off a three-cornered piece, which she put in her pocket. She did not dare to take any other food from the cupboard, for that was near Polly’s room, and the door stood wide open, as is the way in these bush-houses.

A daring project had entered the child’s mind, and she went out again by the verandah to the back of the hut, where was the little skillin-room in which Dick was locked up. By placing a forked log against the window – and oh! What an effort it was for the puny arms! – she could just manage to clamber up, and presently she was at little Dick’s side, and bidding him “hush!” had lifted him in her arms, and was guiding him painfully down to the ground.

They stood out in the pale moonlight – the two children, free to roam whither they would. The lake lay before them – a rippling sea tipped with moonbeams. Janie drew Dick with her, and they ran along the beach and under the shadow of the rocks till they reached a shallow cover which Janie knew.

There was a tiny floating islet at the point of the cove. It was the stump of an ancient ti-tree, which had floated down from the bank of a creek, and gathering to itself soil and refuse, had put forth quite a bushy crop of shoots from its half-withered stem. The twisted mossy roots made a sort of arm-chair beneath the foliage, and hither Janie had often brought Dick, and had sat with him for long hours, eluding her stepmother’s angry search. Here the gulls and pelicans perched, and to-night one white bird with outstretched wings hovered over the greenery and seemed to Janie like the spirit of her dream inviting her to seek shelter there.

With Dick still in her arms the little girl crouched in the hollow of the stump, and leaned back so that the branches closed round them both, hiding them completely, and leaving visible to them only the stars overhead. The night was very warm, and the Southern Cross shone clear, though there were dark clouds low on the horizon. Dick slept peacefully, and the gulls crouched on the furthest bough. By and by Janie slept too. She slept so soundly that she had no sense of rising wind or of heaving waters. When she awoke the sky was lightening. The rosy dawn seemed near, and the land far away. Janie gave a little bewildered cry which awakened Dick. The two children started up, and pushing aside the branches looked out from their retreat.

With Dick still in her arms the little girl crouched in the hollow of the stump, and leaned back so that the branches closed round them both, hiding them completely, and leaving visible to them only the stars overhead. The night was very warm, and the Southern Cross shone clear, though there were dark clouds low on the horizon. Dick slept peacefully, and the gulls crouched on the furthest bough. By and by Janie slept too. She slept so soundly that she had no sense of rising wind or of heaving waters. When she awoke the sky was lightening. The rosy dawn seemed near, and the land far away. Janie gave a little bewildered cry which awakened Dick. The two children started up, and pushing aside the branches looked out from their retreat.

There was nothing round them but water. The floating islet had drifted away in the storm, and they were far out on the great lake. No fear now of Polly’s pursuit. She would never guess where they had gone. The little waves splashed up against the log, and a flock of sea gulls circled overhead. But for the gulls they were alone on what seemed the wide sea.

There are no tides nor currents on this shallow inland sea, and while the wind blew from the slopes beneath which Joe Galvin’s hut was built, the tree islet floated straight for the opposite shore. But as the day got on the wind ceased, and the old stump lay like some shipwrecked hull scarcely making any perceptible movement in the water. At first the children were pleased with the novelty of the scene and the situation. Dick like to watch the birds which still hovered about, and the tiny shell fish that clung to the rotting stump, and the shoals of fish which could be seen distinctly through the clear water. They ate their meal of Janie’s bread, and the afternoon waned, and Dick began to get hungry again, and cried himself into a trouble sleep. Janie’s heart sank, and she wished that the wind would rise and send the stump to shore again. But the wind did not rise, and the child began to realize that unless recuse came they must perish of thirst and hunger upon this motionless sea.

Late the next night Joe Galvin rose up to the station, the master of which employed him, and wild with grief and excitement implored that a search party might be got together to hunt for the two children, lost in the bush. He had come home that morning to hear the news, and Polly in her remorse and anxiety had told him of her plan of punishing Dick, and of how she feared that Janie had taken the boy away to escape the beating she had threatened. Joe Galvin in his fury struck his wife and left her, while he went wandering madly along the lake shore, and through the bush near the hut seeking for tracks and finding none, for the rain of the night before had washed out all marks of the little footsteps. Then he mounted his horse and galloped to the station for help.

It was not long before the search-party set out – the master and two young men of the station, Galvin and four bush-trackers, each two going a different way and searching during the night while the moon lasted. They beat about towards different points of the lake shore, and when there came the pitch darkness before dawn, they made fires and coo-eed. And the master tells how he and Galvin walking together would pause, and start, and rush wildly in some direction when they fancied a child’s cry came, only to find that it was the cry of a curlew or of some other night bird, or the sound of the wind soughing eerily through the oaks.

The wind blew fiercely that night, and the tree-islet with the two little beings upon it drifted back to shore. In the morning the bush-boys found tracks of children’s feet upon a sand hill near the lake. A shout of joy went out, and with frenzied eagerness Joe Galvin followed the tiny footmarks. The trackers lost them again, found them once more, followed them along a gulley bed, and once more lost them. It was almost evening when they stopped at the foot of a little stony hillock attracted by an eagle hawk swirling in the air.

The wind blew fiercely that night, and the tree-islet with the two little beings upon it drifted back to shore. In the morning the bush-boys found tracks of children’s feet upon a sand hill near the lake. A shout of joy went out, and with frenzied eagerness Joe Galvin followed the tiny footmarks. The trackers lost them again, found them once more, followed them along a gulley bed, and once more lost them. It was almost evening when they stopped at the foot of a little stony hillock attracted by an eagle hawk swirling in the air.

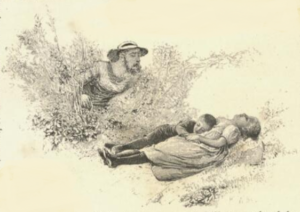

A terrible fear smote Galvin. He motioned to the master to go first, and hung back, his limbs tottering, brawny bushman as he was, like the limbs of one faint to death. The master stepped forward. It was under a rocky knoll overgrown with wattle and scarlet kennedia that he saw the children lying. At first he thought that they had stopped to rest, and were only sleeping. Dickie was clasped tight in Janie’s arms, and Janie lay, her head upon a stone, her face upturned with a smile upon her poor swollen lips. When he went closer he saw that they were dead.

~

References

Praed, Mrs Campbell, “The Sea-Birds’ Message” (1891, short story) in Over the sea: stories of two worlds: 9-13.

illustrations from the original. Painting, “The Sea-Birds’ Message” by H J Johnstone.

I’m glad Australia has given up on ‘lost children’ stories. They’re pretty heart-rending.