by Kylie Tennant (1912-1988)

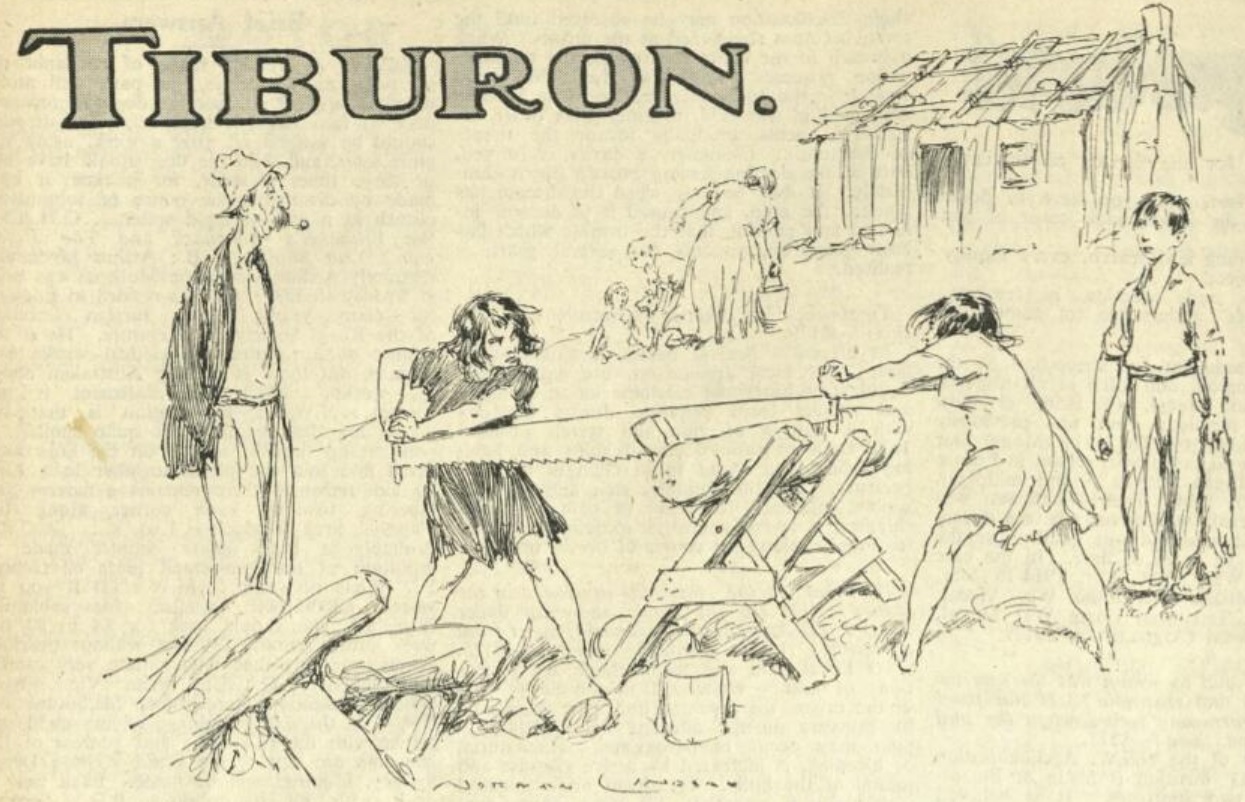

Kylie Tennant’s novel, Tiburon, won the S H Prior Memorial prize for 1935. Illustrated by Norman Lindsay, it was serialised in The bulletin from September 1935 to January 1936. An extract from the novel’s opening is given below, and the rest can be read online via Trove.

Chapter 1

In Tiburon all the shady concrete streets, the well-built bungalows, the plate-glass shop fronts, the garages and banks are clustered together in the middle of the town and ringed round by mean, dusty streets and weatherboard cottages set farther apart as the outskirts are reached.

Three miles from the prosperous shopping centre the main road takes a bend to cross the river below Warning Hill. Here, by Dwyer’s farm, is the travellers camp on a stretch of grazing land rightly belonging to the Pastoral Protection Board and reserved for hungry travelling stock. One of the board’s problems has always been to keep the even hungrier nomad human beings from occupying the land reserved for the use of the animals.

The bagmen had been gradually ousted from the railway bridge and the showground, and Dwyer’s Bend remained their last stronghold. Here the “turnouts” drew in from the road — sulkies loaded high with tents, house-hold gear, children and bedding, with perhaps a spare horse, and certainly a dog or so, trotting behind. Battered old motor-trucks, bottle-oh carts and cars belonging to pedlars of soap, brushes and tinware paused here for the night.

Dusty men pushed their bicycles up the rise, while others came tramping with their “naps” on their backs and the remains of last week’s dole slung over their shoulders in sugarbags.

At dusk the place was lively with the shouting of children and the barking of dogs. Hobbles clinked as the horses moved among the patches of weed and piles of rusty tins. As darkness deepened, little flickers of campfires pricked the dark bulk of Warning Hill; and there were often sounds of singing and fighting.

The shelter shed on the travellers’ reserve, unlike most of the structures erected by charitable town councils, actually did shelter. This was due to rich Mrs. Malloy, who had made herself the council’s curse for many years by her generosity to that “undesirable element” the travelling unemployed. It was she who had built the shelter shed, and, although no one ever used it in dry weather, during the long rainy spells it had saved many a bagman from lying stiff with rheumatism under a bridge.

There were also the shanties occupied by the town’s hard cases, the Willoughbys, the Mulvers, Gran Staines, Mad Peter, an old-age pensioner who had been there as long as anyone could remember, and the Whites.

Dave White had moved out to Warning Hill soon after the police had begun their “persecution.” Old Sergeant Moore not only had him fined for driving a horse with a gaping sore on its back, but had followed that up by bringing him to court again and telling the magistrate all the private details of Dave’s one-room dwelling, in which Dave, his wife and five children shared the only bed.

Deeply hurt by this inquisitiveness and by some remarks of the magistrate, Dave White decided to move away from Tiburon; but by the time he had gone four miles he could not be bothered moving farther. His eldest boy, twelve-year-old Jim, could trap rabbits as cleverly as a man; and between rabbits and child endowment they managed well enough. Dave admitted that their bark shelter needed repairs. He was always going to fix it, but he never had the time. When Jim was fourteen he was old enough to get work, and the other children were quite useful about the place and, as Dave often said, “a real comfort to their old father.” By the time Jim was seventeen he found he could make more money cutting wood and selling it in the town. Dave retired and spent his days in the bar of O’Brien’s Hotel, where he often picked up an order for Jim to bring in a load of wood.

As Larry, Paul and Bill grew up, they were absorbed into the wood-carting business, and Jim found time to build a “peasey hut,” that is, a mud hut, two rooms roofed with galvanised-iron, one for the girls and one a living room. The peasey hut was considered to be something of a masterpiece by the residents of Warning Hill.

The girls were well worth their keep. They not only did the cooking, but as the boys dragged in the timber they sawed it into logs. Dave would never allow them to take a job in the town or on a farm; and when Mary ran away and found a place at Wilson’ s dairy old Dave drove twelve miles after her and made such a fuss that the Wilsons had to let her go even though she begged and cried to be allowed to stay.

“I’ve always fought to keep my family together, my girl,” Dave told her as he drove back. ‘‘An’ I always will. You just remember that. I ain’t goin’ to have my family broken up by nobody.”

Dave’s wife died of a chill complicated by the arrival of her thirteenth child. She had formed the habit of driving into town with Dave and sitting all day in the sulky in the hotel yard watching the people and the motor-cars go by. It was a nice change, she said, from Dwyer’s Bend. Long after closing time she could be seen, sitting like a graven image in the dark, waiting patiently for the rattle of the side door opening, the laughter and voices and the uncertain footsteps which announced Dave’s coming. As soon as she heard these sounds she would climb down, light the lamps, cluck to the horse and move over to make room, while a couple of friends heaved Dave into his seat. Then Blasted, the horse, would go clopping slowly down the road, the sulky creaking and protesting under the weight and the lamps blinking uncertainly until they vanished round the corner by the Chinamen’s gardens.

Mrs. White was a woman contented with very little, otherwise she would never have stood Dave, although, when she married him, he was a good-looking enough chap. She did not mind the perpetual clutter of children, because she hardly noticed them. They had to look after themselves while she stumbled round in her slow way, pottering with a bit of cooking or just sitting in the sun. She couldn’t be bothered cleaning anything, because it only got dirty again. She couldn’t even be bothered talking to the women in the near-by camps, although when she did start she could be quite bloodcurdling in an obstetric style. Winter or summer, she wore the same black hat of straw lace with faded red roses under the brim. In summer a torn, very tight black silk dress, with short sleeves that showed her big red arms, kept the roses company, and in winter the black, silk dress was covered by a brown woollen coat. If there is a ghost haunting the pepper-trees outside O’Brien’s Hotel, it haunts after closing-time and wears a black lace hat with faded red roses.

When Mrs. White caught a chill waiting for Dave one wet night, the town was divided between the opinion that she ought to have had more sense and surprise that anything could kill a White. The local legend reputed them to live on rusty tins and barbed wire.

Dave fortified himself against his loss until he had to ask strangers if it were really a black cat on the fence or not. His horror of any alteration in his life, his dread of change, the feeling that something was opposing his will and breaking up his family to spite him, made the warmth of O’Brien’s bar more attractive than ever.

“It wasn’t the kid,” he mourned, wiping his grey moustache. “She was good for another twenty kids. She always ’ated the wet. Said it got into ’er bones.”

“Cheer up, Dave.” Will Souter patted him on the back. “Cheer up, boy. Never say die.” This struck him as a little tactless. He had not meant to dwell on the uncomfortable subject. He lapsed into silence.

“You got the kids,” Orry Smith reminded him. “You’ve always got the kids.”

[End of extract. You can continue reading the rest of chapter 1 here.]

~

Tennant, Kylie, Tiburon, The bulletin from 4 Sep 1935 to Jan 1936.

What a find, thank you. This looks like a very interesting read.

You’re very welcome, Val. Trove is such a valuable resource, you never know what you’ll find.