by Debbie Robson

For six months during 1917/18 Miles Franklin saw service behind the Serbian lines, with a Scottish Women’s Hospitals unit, which we’ll be looking at over the next two weeks in the run-up to Anzac Day. Below is an edited version of two posts Debbie Robson wrote in 2016, drawing on the work of and collaborating with Alan Cumming and Jennifer Baker.

For six months during 1917/18 Miles Franklin saw service behind the Serbian lines, with a Scottish Women’s Hospitals unit, which we’ll be looking at over the next two weeks in the run-up to Anzac Day. Below is an edited version of two posts Debbie Robson wrote in 2016, drawing on the work of and collaborating with Alan Cumming and Jennifer Baker.

Since 2010 I have been fascinated with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and the Australians involved with this organisation. I have discovered the amazing achievements of Olive Kelso King the hero of the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917; I have found out about the Ostrovo Unit in Serbia where Miles Franklin worked as an orderly and also, amazingly that two Australians, Dr Agnes Bennett and Dr Mary de Garis, were the Chief Medical Officers of the unit.

When war broke out in 1914 the British Government put out a call for doctors and nurses to help on the front line. Scottish surgeon Elsie Inglis (1864-1917) put her hand up but was told: “My good lady, go home and sit still.” Of course she didn’t. She went on to form what soon became known as the Scottish Women’s Hospitals which served the war effort from 1914 to 1919 and were not finally disbanded until 1925.

They started off in Calais supporting Belgian soldiers, but their main locations were four hospitals in France, two in Corsica, two in Greece, one in Macedonia, two in Romania and six in Serbia. There were also a number of satellite hospitals and dressing stations.

On my own site I have documented the dozen or so Australian women who saw service with SWH. They are listed below with brief summaries of their bio’s. And at the end of this article I provide links as well to some of the considerable work Alan Cumming and Jennifer Baker have done in this area.

.

Millicent Sylvia Armstrong (1888-1973)

Millicent was educated at Shirley, Woollahra, matriculated in French and Latin in 1905, and followed her sisters Ina and Helen to the University of Sydney (B.A., 1910), graduating with first-class honours in English and writing a story for Theatre magazine (as ‘Emily Brown’). She left Australia for London in August 1914 hoping to find a publisher for her first novel, but was almost immediately involved in war-work, probably in canteens.

From 1916 Millicent was attached as an orderly to a unit of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service and worked from March 1917 at the ancient Abbaye de Royaumont, Asnières-sur-Oise, France. She was sent to the advance hospital at Villers-Cotterets, Aisne, which was taken over by the French military and became Hôpital Auxiliaire d’Armées No.30, where she first experimented with drama. Written partly in English and partly in French, and solely as entertainment for the wounded, her pantomimes, melodramas and variety shows were performed by staff and some of the casualties, using makeshift props and costumes. In the face of the German advance in May 1918, the hospital was evacuated to Royaumont: Miss Armstrong was awarded the Croix de Guerre for her bravery in rescuing wounded soldiers while under fire.

Post-war she was a farmer (a soldier settler) and had a number of plays published and performed.

Mary Josephine Bedford (1861-1955)

Josephine Bedford arrived in Brisbane in 1891 with her longtime friend and companion Dr Lilian Cooper, with whom she shared accommodation during their student days in England. She helped Lilian establish herself as Queensland’s first female doctor while pursuing her own interest in improving the welfare of the state’s women and children, leading to the creation of the Crèche and Kindergarten Association in 1907. By 1911, four centres were operating in Brisbane and a college for kindergarten teachers had been established.

On an extended trip overseas, Josephine studied the concept of ‘supervised play’, returning after the War to help open two supervised playgrounds (in Paddington and Spring Hill).

With Dr Cooper, she joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in 1915, serving for twelve months, including a time in Macedonia, where she was awarded the Serbian Order of St Sava, fourth-class..

Agnes Bennett (1872-1960)

Bennett attended Sydney Girls High School [a year or two behind Louise Mack and Ethel Turner], as well as Cheltenham Ladies’ College, Dulwich Girls’ High School and Abbotsleigh. She won a scholarship in 1890 and studied science at the University of Sydney (B.Sc., 1894); she was secretary of and a night-school teacher for the Women’s Association (later University Women’s Settlement).

Initially unable to find a job as a medical practitioner, Bennett worked for a time as a teacher and governess, then left Australia in 1895 to study at the College of Medicine for Women, University of Edinburgh (M.B., Ch.M., 1899). She returned to Sydney in 1901 and set up in private practice in Darlinghurst Road but although she gave free medical advice she was forced to give up her practice because of the then common prejudices against female doctors. She briefly worked at Callan Park, the hospital for the Insane, before leaving in 1905 to take over the practice of a woman doctor in Wellington, NZ. This time the practice thrived. She was chief medical officer at St Helen’s maternity hospital, and honorary physician to the children’s ward of Wellington Hospital from 1910. In 1911 she completed her M.D. at Edinburgh.

In 1915 Agnes Bennett became the first female commissioned officer in the British Army, when as a captain she worked as a medical officer in war hospitals in Cairo. When this work came to an end she sailed for England, where almost immediately she met up with Elsie Inglis in London who asked her to work with the SWH. On the 2nd August 1916, the America Unit, in the command of Dr Bennett, sailed for Salonika on the hospital ship Dunluce Castle, arriving on the 13th August.

Originally intended as a base hospital at Salonika, the unit’s status was changed. As the only hospital for the use of the defeated Third Serbian Army, it would now be situated near the front, acting more or less as a casualty clearing station. Finally on the 7th September 1916 the first vehicles of her thirty-nine car convoy left Salonika on the road to Ostrovo Lake. By the 11th September, Dr Bennett was able to record of the Ostrovo Unit. “The hospital is gradually getting into being-progress slow, partly on account of labour.” By the 28th September she was writing: “We have admitted 204 patients up to today; ten of the staff are ill which means 14 off work…”

While Chief Medical Office of the Ostrovo Unit, Dr Bennett was concerned with the difficulties the unit faced being so far from the front. Far too many men were losing their lives through the delay in getting them down to her hospital.

There was also the problem of malaria. Although, Ostrovo was up in the hills and the malaria threat was not as bad as in Salonika, it still claimed lives and would ultimately end her term as CMO when she fell victim as well. Gradually as the Serbs pushed the enemy back, the hospital work eased. In late October she wrote: “Our 400th patient admitted today.” By winter, conditions became more severe. Fighting died down and the roads became impassable. The hospital was nearly isolated. Cases of scurvy were brought in occasionally, for food was short in the front line. In December a site was chosen for the outpost hospital at Dobraveni and the personnel sent off.

In the new year Dr Bennett was plagued by internal problems and worry over the outpost at Dobraveni. By late winter German air raids became more frequent and the outpost was moved in March with the help of 100 German prisoners. With summer came the threat of malaria again. Dr Bennett succumbed to the disease and was forced to resign, being replaced by another Australian, Mary De Garis.

Lillian Cooper (1861-1947).

Educated privately, Cooper dedicated herself to medicine when young. Despite parental opposition, she entered the London School of Medicine for Women in 1886, completed the course in October 1890 and, after passing the conjoint examinations of the Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh, the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, and the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow, received a licentiate from Edinburgh.

Cooper worked briefly and unhappily for a practitioner in Halstead, Essex, then came to Brisbane in May 1891 with her lifelong friend Josephine Bedford, and in June became the first female doctor registered in Queensland. In 1905 she became associated with the Mater Misericordiae Hospital and stayed with it for the rest of her life.

In 1911 Cooper returned to England. Travelling through the USA, she visited the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and Johns Hopkins Hospital in Maryland; before going on to win a doctorate of medicine from the University of Durham in June 1912.

With Miss Bedford she joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in 1915, served for twelve months, including a time in Macedonia, and was awarded the Serbian Order of St Sava, fourth-class.

Elsie Jean Dalyell (1881-1948)

Elsie studied medicine at Sydney University, receiving her Bachelor in Medicine in 1909 and becoming one of the first women in the faculty to graduate with first class honours. She completed a Master of Surgery in 1910.

On the outbreak of war she offered her services to the War Office, only to be refused because she was a women. Her involvement in the war began in 1915, working with the Serbian Relief Fund in Skopje. Employed as a bacteriologist in Serbia and France she was well known to turn her hand to all sorts of work when required.

In 1916, with SWH at Royaumont Abbey in France, she excelled in her work with the complicated gas gangrene and other infectious wounds of war. Elsie joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1917,together, these commitments took her to France, Greece, Malta and Turkey.In 1919 she was appointed an Officer of Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.) and was decorated by the Government of Serbia.

Mary De Garis (1881-1963)

In 1898 Mary De Garis was dux of her year at the Methodist Ladies College in Melbourne. In 1900 she was just the thirty-first woman to enrol in Medicine at the University of Melbourne. She was awarded a Bachelor of Medicine in 1904 and Bachelor of Surgery in 1905. She was then appointed to two resident positions, at the Melbourne Hospital in 1905–06, and the Women’s Hospital from 1906–07. In 1907 she became the second woman in Victoria to be awarded the Doctorate of Medicine.

In 1916, wishing to be closer to her fiancé she sailed to London, working at the Manor Hospital for five months. Until, on her fiancé’s death at the battle of Pozieres in August 1916, she joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and was posted to the America Unit in Ostrovo, Macedonia from February 1917 to October 1918. succeeding Agnes Bennett as Chief Medical Officer.

Laura Magaret Fowler (1868-1952)

Fowler was the first woman to enrol in medicine in South Australia. After graduating she completed her residency at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital, and in 1892 became the first woman to be elected to the SA Branch of the BMA. In 1893 she married Cr Charles Standish Hope, and the couple left for Bengal as medical missionaries. During the course of the next 20 years they practised at various mission hospitals throughout India.

In 1915, while in England, the Hopes joined the SWH and were sent to Serbia. They were captured by Austrians in November 1915, held for two months, then deported to Hungary. They found their way to England and returned to mission work in India.

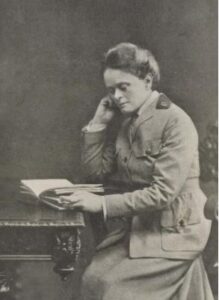

Stella Miles Franklin (1879-1954)

Miles Franklin was an orderly in the Scottish Women’s Hospital, “America Unit”, from July 1917 to February 1918. The hospital was located on the shores of Lake Ostrovo (now Vegoritis), and at the foot of Mt. Kaimakchalan, about three miles north of the railway station in the village of Ostrovo (now Arnissa)

Franklin wrote a piece “Somewhere in the Balkans” and two manuscripts dedicated to the Serbs: “By Far Kaimakchalan” and “It Matters Nothing – Six months with the Serbs” [from which AWWC will publish excerpts and a review over the next two weeks]. The manuscripts have never been published, but are kept with all Franklin’s papers at the Mitchell Library in Sydney.

Agnes Dorothy Kerr (1870-1951)

Not much is known about Kerr but she is mentioned briefly in the writings of Miles Franklin. She was a dressing station sister with the Ostrovo Field Hospital and later Matron at Burketown Hospital, Queensland.

Olive Kelso King (1885-1958)

Educated at home, at Sydney Church of England Girls Grammar School and later in Germany, King led an adventurous life that included climbing Mexico’s Mount Popocatepetl with three male companions.

When war broke out Olive was in England. She served briefly as an ambulance driver in Belgium, supplying her own vehicle, a lorry which she had converted into a 16 seater ambulance and christened ‘Ella the elephant’. In 1915 she joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals Girton and Newnham Unit and was sent to the Sainte-Savine field hospital, near Troyes, in France.

In November 1915 the unit was sent to the Macedonian front, landing at Salonika, Greece and moving up to Gevgelija on the Greco-Serbian border. Six weeks later the Bulgarian forces were advancing rapidly and the hospital had to be evacuated in twenty four hours, a seemingly impossible task for 30 women. But by midnight, helped by 40 Royal Engineers, the whole staff had got away except for the three female chauffeurs. It was King’s decision to head for the nearest railway station. They managed to get themselves and their ambulances on the last train before the station was bombed. Thirteen French ambulance drivers, who tried to make their way to Salonika via a rough track by Doiran, were ambushed by the Bulgarians, their vehicles taken and all were killed or taken prisoner.

By the end of July 1916 Olive had left the SWH and joined the Serbian army as a driver attached to the Headquarters of the Medical Service at Salonika. By this time the Serbs had lost most of their transport and ‘Ella’ was one of only three cars attached to the Medical Headquarters.

On 18 August 1917, the day of the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, Olive Kelso King transported people and records to safety, driving for twenty four hours at a stretch. For this she was awarded the Serbian silver medal for bravery.

After the war Olive set up seventeen canteens in Serbia to provide necessities at cost price or below. The last canteen closed in 1920. She was awarded the Order of St Sava for her post-war efforts.

Edith Jane Mackay (1873-1959)

A nurse, Edith was in Great Britain when World War 1 broke out. In 1915, she joined the SWH and was sent to Lourdes France to work for the French Red Cross. In 1917, she was sent to Corsica to nurse war veterans, and was Matron of a military hospital in Ajaccio, Corsica from October 1917 to September 1918.

Edith then moved on to the Balkans and was in Serbia in 1919, where she received the Serbian Medal for Zeal and later performed relief work during the Russian famine.

Harriet Christina Newcombe (1854-1942)

Newcombe and her partner Margaret Emily Hodge (1858-1938) were feminists and educators who came to Sydney from Britain in 1897, intending to work among the poor. There they became involved in the women’s suffrage movement and had a wide circle of friends including Rose Scott, Vida Goldstein and Miles Franklin. By 1910 they were back in England, but remained involved with Australian feminists.

At the outbreak WW I, Newcombe was occupied with relief work, in particular the distribution of clothing sent from Sydney by Dr Mary Booth’s Babies’ Kit Society for the Allies’ Babies. In 1916-18 she was on the London committee of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service.

Alice Mary Stirling (1885-1925)

Adelaide-born Stirling was “an indefatigable war worker, and took part in many movements in aid of wounded soldiers”, initially in Rouen (France), where she was engaged in canteen work; then back in London at St. Dunstan’s Hostel for blinded soldiers and sailors. On joining Scottish Women’s Hospitals she was an orderly and driver at the hospital near Salonika.

.

Further reading:

Debbie Robson, Australians working with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals

Debbie Robson, Centenary Commemorations of Dr Elsie Inglis and SWH

Alan Cumming, Inside story of BBC WWI documentary re SWH in Serbia

Alan Cumming, The Women Who Went to War – A Great Adventure (movie)

Alan Cumming, Scottish Women’s Hospitals (movie)

Jennifer Baker, Looking for the Evidence: WWI Australian Women Doctors

Eva Shaw McLaren, A History of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (Google Books)

WAD Holloway, The Australian Legend: Miles Franklin’s War

Ivan Čapovski, The Sorrow of Miles Franklin beneath Mount Kajmakčalan (review)

.

Debbie Robson lives on the NSW Central Coast. She is the the author of Tomaree, a WWII love story set in Port Stephens, New South Wales, Australia and Crossing Paths: the BookCrossing novel.

Currently enjoying Gail Jones’s historical novel Salonika Burning where she imagines Miles Franklin and Olive King’s time in Salonika.

Mary, I’m the editor who put this up. Franklin was barely in Salonika, except passing through. I’m getting the impression Gail Jones ‘stretched’ the MF story a little, which I think is a shame when the real facts are not very well known.

However, there is another novel I enjoyed, by a Macedonian author who treated the MF story with a great deal of playfulness – The Sorrow of Miles Franklin beneath Mount Kajmakcalan.

Anyway, I hope you enjoy the rest of our four part series.

I’m sorry to hear Jones stretched the truth. I read Franklin’s diaries from that time and what I remember now is mainly her trouble with chilblains and her run-ins with matron.

Thanks so much for doing a wonderful job of editing Bill and its lovely you have listed all the Australian women I’ve been able to find who served with the SWH.

Thank you so much Bill for doing such an excellent editing job and showcasing these amazing women. I was so pleased to see you had listed them individually.

I’m sorry to hear that Jones has stretched the truth. I read Franklin’s diaries from that time a while ago now and all I remember is mainly her writing about her chilblains and her run-ins with matron.

Thanks for the post, Debbie. I can see why you became fascinated with this subject. So many extraordinary women!

It definitely is. They were so brave and in my unpublished manuscript I tried to highlight how difficult it must have been to return to “normal” life.

It is so exciting to hear about Australian women from the past who were active in ways most of us had no idea about. It’s so sad that for so long we knew little or nothing about them.

My opinion exactly WG. Did you see Mary de Garis in there, the sister of the de Garis you wrote about ‘recently’ from Mildura.

Oh no, I didn’t make that connection Bill. I am distracted by our move at present, so my reading brain is only operating at 50%. I’m trying to finish a 1940 review post, which might interest you, and prepare for Jane Austen on Saturday, plus more stuff. Something’s gotta give!

I’ve done a lot of research to compile the list from various sources and I’m always on the watch out. I’m sure there are Australian women who have been missed. Recently an article posted two new names of Australian women working with the SWH. Unfortunately the writer hadn’t checked her research. Yes they served in WWI but with independent units not with one of the SWH units.

Thanks Debbie. I bet it’s been engrossing work.

Please see these books by Bojan Pajic, published by Australian Scholarly Publishers, Melbourne in 2018 and 2022:

Our Forgotten Volunteers-Australians and New Zealanders with Serbs in World War One

Australians with Serbs in World War One

I will definitely have to have a look Bolan. Thank you.