The wonderful series of initiations was ended, and with the corroboree season over the natives came back to their work on the stations and in the township. I could understand now the reason of their swift passing from a world in which they were long belated, and from contact with the white man’s civilisation, which can find no place for the primitive.

The year’s work with the cattle began, and the desire came to stock up my own run of 183,600 acres on Ethel Creek, in the Windell area of north central Western Australia. The frightening names of the locality — Ophthalmia Ranges, Dead Man’s Hill, Grave Creek, and so on, had hitherto deterred other pastoralists from contemplating settlement there, but they appealed to me, and on my previous journey by buggy I had found that far-out area an encouraging proposition. There was water in plenty, and at shallow depths, good feed in all seasons, and the run was within easy distance of Peak Hill and other goldfield markets. I named the property Glen Carrick, in affectionate remembrance of a cousin in England, and set about the purchase of the cattle to stock up.

To watch my mob of 770 well-fed Hereford’s, placidly browsing round the fringe of Lake Eda, some 40 miles east of Broome, brought back vividly to my mind the inspired lines of Adam Lindsay Gordon, Banjo Paterson and other Australian poets whose stirring verses lift droving to the realms of high adventure. How little I knew!

Today I detest even the picture of a Hereford cow. I loathe their white-washed faces, for I have ridden behind them, with eight of my own drovers, for six months, 1,000 miles as the route went but some 3,000 as I rode it, zig-zagging behind the mob at six or eight or ten miles a day, and everyone of the 770 surpassing the Irish pig in contrariness. This great mob, perhaps the largest number that had travelled down from the West Kimberleys in a single herd, was duly lifted from Lake Eda.

Stores and equipment I obtained from Broome, also a cook, who was a Maori half-caste, for Broome was mostly ‘breed’ in those days, with just a few decent whites to leaven the mass. Sundry droving hands were also engaged, whose knowledge of the gentle art about equalled mine.

We all armed ourselves with the long stockwhips of story and poem, and while the head drover and his lieutenant were mustering and branding, tried to flourish our whips in true stockman style. After much climbing into the trees to disentangle the lash, the stockwhips were quietly rolled up and hidden in the dray, a humble buggy-whip or less ambitious instrument of sapling and twine taking their place.

My equipment was a good English pigskin side-saddle with ordinary stirrup; three pairs of laced wallaby skin shoes; three habits, one of good British cloth, the other two of stout holland; a felt hat, three pairs of riding gloves, and plenty of fly veiling. A compact hold-all and portmanteau carried all necessaries, and was easily accessible on the dray, which also carried the stores for the trip and the drovers’ swags.

I undertook the purchase of the ‘plant’ myself. Besides the four fine draught horses, there were some 30 riding horses for the use of the drovers, myself and my son, aged 12. There were a few good stock horses in the mob, but not one of the drovers owned a cattle dog, a most necessary adjunct to droving.

On a golden day in the Australian April we lifted the big mob from Lake Eda, and started off behind them. The head drover assigned each one his position and duties. Some guarded the flanks, the leader and his second headed the mob; the Maori cook, Davy, took complete charge of the dray, provisions and spare horses, and the others became, the “tailing” hands.

A travelling mob of cows usually shapes itself in the form of a triangle, the strongest beasts forming the apex, while the stragglers make an ever-widening line at the rear in their efforts to find food, as the leaders and flankers consume almost every blade as they go along. All the cattle had been accustomed to surface water, and while the going was over the claypan and well-grassed country south of Broome, the big mob travelled easily. My place and that of my boy, which we retained throughout the journey, were the base of the triangle, zig-zagging to and fro behind the “tailers”.

There is no eight hours day in a droving camp. All hands are roused at peep of dawn. Davy had breakfast ready and steaming, horses were brought in and saddled, and the mob was waked and started. At each night-camp, many of the mothers hid their calves, hoping to make back to them later. To watch a cow hide its calf behind a 4-inch tussock is a lesson in wild mothercraft.

Sunrise generally saw us on the move, the leaders grazing and the stragglers finding their places at the tail. Back and forth along this ever-widening tail of cows and calves we rode, with eyes alert for break backs. Meanwhile the head man went on to find a night-camp.

Davy followed the horse-track, and only twice failed to turn up in time. Even so, he incurred my

extreme displeasure on one occasion. The only green stuff I had had to eat for weeks, a fresh young lettuce presented as a gift of grace at one of the stations, he took away and boiled!

All went well until the Eighty-mile Beach was reached; here the surface waters ceased, and the wells began. Six canvas buckets, each with a 20-gallon capacity, with pulleys and gear, were brought for emergencies. Most of the wells along the Eighty-mile were in a bad state at the time, owing to the disuse of the stock-route, and there was hefty work for all at the end of each day’s droving.

The long-disused windlasses, timbering and platform more than once gave way, burying buckets and gear, and effectually closing the wells, so there was nothing for it but to move the thirsty mob onward. The wells were far apart, and cows in calf are slow walkers.

At Whistler’s Creek, near Lagrange Bay, the sea became visible and with “hurrah swing” of waving tails, the beasts rushed into the bay. Fortunately the water was shallow at that point and they were soon on the road again.

Nambeet Well, half-way along the Eighty-mile, was the first good well struck, a shallow soak with beautiful and abundant water. Beside the well was a corrugated iron tombstone, telling of the murder of a white man named Hourigan by his native boy for a few ends of tobacco. The boy was caught and hanged.

Old breakwinds on the slopes surrounding the valley of Nambeet Well showed that the place was once a favourite camping ground, but after the murder no natives would camp there. Some poisonous or stupefying herbage laid a score or so of our cattle apparently dead there, but we heard later that they all recovered, and made back to their own ground.

The coastline along the beach is only 10 to 12 feet above sea level, and in all the long stretch of plain only two little pinnacles— Barn and Church Hills— raise their heads above the level. A species of bloated rat, with a thick tail, makes shallow burrows on the plain, and these pitfalls added to the difficulty of manoeuvring the thirsty mob.

Along the whole length of the beach we had to carry our firewood to the dray. There was but one tree, an unburnable “thorny sand-paper”, left standing, covered with axe-chops and impregnable still.

The first stampede occurred at Barn Hill, and standing on the little knob, I looked down on a sea of horns and tails and dust as the whole mob suddenly started back for home and water. At last the galloping drovers “headed” them again, the sea of dust subsided, and the runaways were under control.

All along the coast, and right out to the bays, are fresh springs bubbling up through the mud, and at low tide one can see and taste the beautiful fresh water. Smoke signals of the natives we could see on the horizon every day, messages carried on for many miles. The signals were all identical— a long spiral drifting away to the south.

The inlanders were even in those years coming in to the coast from ever-increasing distances to replace the coast groups that had died out, until they in their turn had succumbed to the new conditions. Practically all the coastal natives are now dead, those frequenting the town-ships and beaches being far inland “relatives” of the dead tribes.

The long day’s tailing made riding very wearisome, and I frequently changed to the off-side. I noticed that many of the drovers rode side-saddle now and then, but generally the quick and arduous work of the wells relieved the weariness of the saddle. Gradually the Herefords became used to the wells, and our only trouble was the rush to the troughs.

We had hoped to reach Glen Carrick before any calves were dropped, so no lorry had been brought along for day-old calves. Many had to be killed, owing to forced marches, and their mothers gave endless trouble and made night hideous with their bellowing. All-night watches, with great fires at various points, became the rule. More men were needed, and I had to go back to La Grange Bay to telegraph for extra hands and horses.

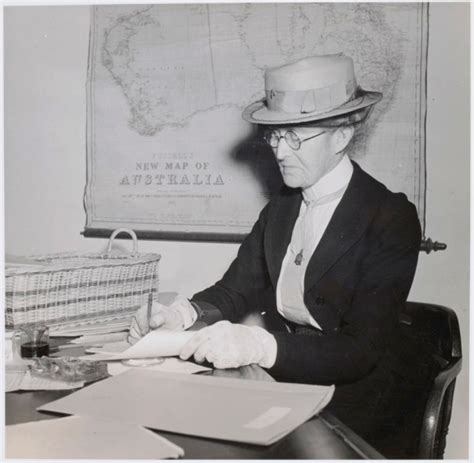

This is story no.6 from The Passing of the Aborigines and no.8 from My Natives and I (serialized in the West Australian, 1936). “In this, the eighth chapter of her memoirs, Mrs. Daisy Bates,C.B.E., describes her experiences during the droving of cattle from Lake Eda, 40 miles east of Broome, to Ethel Creek, near the Ophthalmia Ranges [north east of present day Newman, WA]”

This is story no.6 from The Passing of the Aborigines and no.8 from My Natives and I (serialized in the West Australian, 1936). “In this, the eighth chapter of her memoirs, Mrs. Daisy Bates,C.B.E., describes her experiences during the droving of cattle from Lake Eda, 40 miles east of Broome, to Ethel Creek, near the Ophthalmia Ranges [north east of present day Newman, WA]”

Is it fun to choose the short story that accompanies the essay, or does it feel like a bit of pressure to choose “just the right one”? (I didn’t read this one–I’ve been on the screen too much this week in general–but I do like a story with a cow, or two.)

All eight stories from My Natives and I – and doesn’t that title tell a story itself – were available on Trove (the online database of newspapers and journals maintained by the National Library) so choosing one was easy, for a change, but still had to be edited for OCR misreadings (thankfully, another volunteer had been before me) and to remove all the breaks.

But ‘fun’? Maybe. We set ourselves tasks, and we carry them out.