by Bill Holloway

Daisy Bates (1859-1951), if she’s remembered at all these days, it’s as the little woman, in long Edwardian dresses who lived in a tent alongside the Aboriginal community at Ooldea, way out on the Nullarbor, in western South Australia. But to get there she abandoned society, husbands, a son, a cattle station, and became a self-taught anthropologist whose work is still relied on today.

Daisy Bates (1859-1951), if she’s remembered at all these days, it’s as the little woman, in long Edwardian dresses who lived in a tent alongside the Aboriginal community at Ooldea, way out on the Nullarbor, in western South Australia. But to get there she abandoned society, husbands, a son, a cattle station, and became a self-taught anthropologist whose work is still relied on today.

As best we can tell, and Daisy Bates clearly sugar-coated her backstory, she was born Daisy May O’Dwyer, of the minor Irish (protestant) gentry. Her mother died early (in 1862) and Daisy was brought up mainly by her Grandmother Hunt, in rural Roscrea. There, in the care of her illiterate, Catholic and superstitious nanny, she mixed freely with the rural poor who, in the years after the Great Famine were still living lives not only of intense physical poverty but also of great spiritual richness, which, years later, she said, enabled her to emphasize with and share the lives of Aboriginal Australians.

She somehow, received a fair education, not staying long at any school but guided by her father in her reading, particularly Dickens, and later touring Europe with the family of Sir Francis Outram, learning grammar, languages and manners with their governess. In 1883 her father died, leaving her a small inheritance, and she, like a great many of her fellows, chose to emigrate, in her case to Australia, to another friend of her father’s, Bishop Stanton in Townsville, Queensland.

Some time in her first year in Australia she took a position as governess on a station near Charters Towers, where she probably married Edward Henry Murrant (the famous Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant). She may also, the following year, have married Ernest Baglehole a well-born seaman whom she had met on the voyage out, and further, by her own account was also in the same year to have married Phillip Gibbs, who inconveniently died. In any case she subsequently married Jack Bates, a drover, in 1885 and by him, a year later, had a son, Arnold. And that was the end of intimacy, ‘“I had rather a hard time of it with the baby,” she is reported as saying, “and Jack, the best of men, never came near me after that.”’

She and Bates persevered for a number of years, thinking, or hoping, that he would use her money to establish a cattle property suitable to her station, but Bates, an archetypal ‘lone hand’, was, perhaps not surprisingly, happier to be away droving. Daisy would sometimes go with him, travelling throughout the backblocks of eastern Australia and learning the bush skills that stood her in such good stead in later life. But, by 1894 she had had enough. She placed Arnold in a Catholic boarding school and set sail for London.

There, near destitute due to the property crash and bank failures of 1892, Daisy was doubly lucky to be taken up by the philanthropist W.T. Stead, for he not only found her a place in a home for penurious gentlewomen, but gave her a job on his journal Review of Reviews and so introduced her to journalism which was to provide much of her income for the rest of her life. She stayed at the Review for two years, starting off by dusting the library and learning to type and ending as assistant to the (lady) editor of Borderland, a journal of spiritualism. Although the circles she moved in included both spiritualism and women’s emancipation she was impressed by neither.

In 1897 she took another library position in Norfolk where she mixed with the county set and, apparently accepted as a widow, and with introductions from one of her innumerable upper class cousins, she attended weekend house parties, “hunting and shooting” during the day and dancing at night. At least two men she stayed with, Richard Attwater of Ratfin Hall and Carrick O’Bryen Hoare, were sufficiently taken with her to propose marriage, but in 1899 her bank offered to refund her a shilling in the pound (ie. one twentieth of her nominal deposits), Jack wrote to say he and Arnold were in Western Australia looking for a property in the newly opened up North West and Daisy sailed for Perth. Two years later, the property finally purchased, Daisy named it Glen Carrick, in remembrance no doubt of all she had given up.

Prior to leaving England, she had contacted The Times and offered to investigate for them accounts of clashes between settlers in the north and the Aboriginal people they were displacing. Further to this ambition she was able to obtain an introduction to elderly Catholic priest and champion of the Aboriginal cause, Dean Martelli who was returning to Perth on the same ship.

In Perth she moved in the upper levels of society, gave lectures at, and was accepted into the Karrakatta Club, was invited by its members, Perth’s principal matrons, into their homes, attended Government House, and was persuaded by the Premier, John Forrest, of the necessity of recording Aboriginal languages and customs before they died out.

I wrote of Daisy’s trips through the north west last week – travelling by buggy through largely trackless desert scrub from Cossack out to Roy Hill and back down to Carnarvon; and droving cattle south from Broome to Roy Hill and on to the 180,000 acre station she had bought at Ethel Creek – and if you’re at all interested you can read her stories in her own words in The Passing of the Aborigines, which is still in print.

After the failed attempt to stock Glen Carrick, Daisy worked as a freelance journalist for a couple of years, travelling throughout southern Western Australia. Importantly, in 1904 she wrote her Times story, defending pastoralists against charges of exploiting the Blacks, cementing her acceptance by officialdom as an authority on all things Aboriginal, and in May that year she was appointed by the Registrar General to record the customs and dialects of the Aboriginal population “before they died out”.

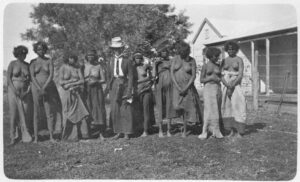

For a year, she worked from an office compiling reports collected by officials throughout Western Australia. Then, taking advantage of some remaining Noongar living on Maamba reserve, a swampy area ten miles south of Perth, she was, reluctantly, permitted by the authorities to camp with them, which she did, in a tent ‘fourteen feet in diameter’, for the next six years (here). During this period, she wrote and rewrote her grammars, corresponded indefatigably with anthropologists interstate and overseas, and published popular articles in the local papers, all the while struggling with the government for ongoing support.

In 1910, almost ready to publish her formal study, she was persuaded to join a major expedition by Oxford and Cambridge Universities, under the leadership of A.R. Radcliffe-Brown (later Australia’s first professor of Anthropology at Sydney University) and, inevitably, her ‘amateur’ work was subsumed into his and the opportunity for publication was lost.

In 1910, almost ready to publish her formal study, she was persuaded to join a major expedition by Oxford and Cambridge Universities, under the leadership of A.R. Radcliffe-Brown (later Australia’s first professor of Anthropology at Sydney University) and, inevitably, her ‘amateur’ work was subsumed into his and the opportunity for publication was lost.

In 1912, she applied for the position of Protector of the Aborigines for the Northern Territory, for which she was unsuccessful ‘as the risks involved would be too great for a woman’. Instead, and somewhat inconsistently, she was offered the, unpaid, position of honorary protector at Eucla on the SA/WA border. She put her property up for sale and moved there, initially staying with friends, then camping once more, on the edge of town, venturing out into the desert for days at a time with Aboriginal companions, on horseback and by camel-drawn buggy, exploring and hunting wild dogs. Already well known throughout the country due to her both own and other journalists’ reports of her activities, she now became a ‘legend’. In 1914 she drove for two weeks in a camel drawn buggy to get to Adelaide for meetings of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

After the war (WWI) she moved to Ooldea, a fettlers’ camp and water stop for steam trains on the newly completed Trans Australia railway, where she was to stay for the next 16 years, all her money gone, an object of curiosity to passengers, with no hope of official support, but still, determinedly, writing up her observations.

Ernestine Hill, who sought her out in 1932, wrote:

Living unafraid in the great loneliness, chanting in those corroborees it is death for a woman to see, she had become a legend, to her own kind… To the natives, she is an age-old, sexless being who knows his secrets and guesses his thoughts – Dhoogoor of the dream-time. (Hill 1937, p.252)

Following Hill’s visit, and her widely syndicated articles, Daisy began, slowly, to benefit from her renown, she was asked to Canberra to advise the government (her suggestion of a huge reservation with a white administrator from Britain, “an Anglican and a gentleman”, was not taken up), she was awarded a CBE, and some of her papers were sold to state and national libraries. Although she refused all requests to collaborate with ‘real’ anthropologists, in 1934 she was persuaded by Hill to work with her on the series of articles eventually published as The Passing of the Aborigines.

For four years Daisy worked to prepare her papers, 94 folios in all, for the National Library, for the pittance of £2 a week, living in a tent north of Adelaide, and then, 80 years old, half blind with sandy blight, and with the nominal title of Consultant for Native Affairs, she returned to Ooldea.

In 1945 she was admitted to Port Augusta hospital suffering from malnutrition. She struggled for a few more years in Adelaide and Streaky Bay to obtain funding for further publications but in 1948 she was admitted to a convalescent home, and on 18 April 1951 aged 91 or 92 she died, an Independent Woman and a Legend.

References and other reading:

Daisy Bates, The Passing of the Aborigines, first pub. 1944 (review)

Elizabeth Salter, Daisy Bates, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1971

Sussanah de Vries, Desert Queen, Harper Collins, Sydney, 2008

Ernestine Hill, The Great Australian Loneliness, Robertson & Mullens, Melbourne, 1945

MRS. DAISY BATES’ RESEARCHES‘

Daisy and her union with Breaker Morant make it into my book, ‘Jonty’s Journey.’ The stories of both people is amazing.

Thanks for commenting Sara. I’m not a fan of Breaker Morant but his is certainly an interesting story (and he seems to be another who sugar coated his backstory).

Interesting that they never divorced. Daisy was a bit of a rebel too.

So impressive! It’s interesting to think how many people were creating fabulous narratives for their backstories, so many years ago; now, with a plethora of social media profiles, many continue this pattern. Different, of course, but not all THAT different after all.

I think people have always found ways to make themselves appear more glamorous than they were. Susanna de Vries wrote a biography of Daisy, Desert Queen, which says she was a governess who got caught having it off with a guest (or family member, I forget) – which sounds like Daisy, but does not explain the money she had on hand to buy Ethel Creek.