As the Australian Women Writers Challenge forges ahead into its fifth year, we’re proud to continue our support not only for Australia’s women writers, but also for writers who face under-representation because of their sexuality, gender identification, ethnicity or ability. VIDA, the organisation for women in literary arts in America which collates statistics on reviewing, has acknowledge the importance of recognising these voices and now include them in their annual count. In Australia, the Diverse Writers of Australia organisation is also engaged with monitoring the diversity of our literary scene.

These initiatives are important, for just as there is never one way of reading the world, so too is there is never one way of writing it, particularly when one’s experiences are shaped by disability. This month we’re holding a focus on Australian women writers with disability to highlight how disability can inform one’s writing in creative and indelible ways.

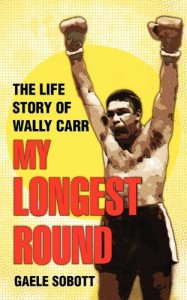

Our first guest post comes from Gaele Sobott, a writer and producer. Gaele has published essays, children’s books, short stories, oral histories and the biography, My Longest Round: the Life Story of Wally Carr. As the director of Outlandish Arts, she recently produced the Australian tour of Caroline Bowditch’s Falling in Love with Frida. Gaele is currently completing a collection of short stories set in Lakemba and has been commissioned by Urban Theatre Projects to write for ‘The Home Project’, a major new Australian work set to be staged in Blacktown early 2017. In her post below, she describes how her experiences of reading and disability have begun to influence her literary craft.

No Trifling Matter

My awareness of the politics of disability came relatively late in life.

My awareness of the politics of disability came relatively late in life.

By the time we moved to Botswana in the late seventies I had a pretty strong sense of social justice. My parents were active in the Eureka Youth League and union movement, while in my teens I hung around the edges of the Vietnam War Moratorium in Melbourne and was influenced by the Women’s Liberation, Aboriginal Land Rights and Anti-Apartheid movements. Yet disability wasn’t on my radar.

In 1991 I completed a degree in English Literature and History at the University of Botswana, then moved to Hull, England, to do post graduate research in gender studies and African literature. During this time I started falling. I could no longer run or dance. I found it difficult to climb stairs, use public transport, and walk. I returned to Australia in 2000 and was eventually diagnosed with a form of muscular dystrophy.

Before I was diagnosed, I had for a long time chosen to read books by women writers. I devoured African writers such as Bessie Head, Ama Ata Aidoo, Buchi Emecheta, Nawal El Saadawi, as well as African-American writers, including Alice Walker, Marge Piercy, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, Toni Cade Bambara. Although I didn’t articulate it at the time, I was beginning to understand how impairment, mental illness, bodily and behavioural differences may be inextricably linked to social contexts. Audre Lorde fuses the personal and the political as she reflects on her experience of breast cancer; Velma Henry, in The Salt Eaters, is sick because of racist and sexual injustice; Toni Cade Bambara writes “. . . being well is no trifling matter.” In A Question of Power, Bessie Head depicts childhood experiences, Apartheid South Africa, and her position as a refugee in Botswana as being central to the protagonist Elizabeth’s mental distress. Wellness for Elizabeth is linked to the earth, to belonging to land and community, to coming to terms with personal history. I now see this book as the text that introduced me to the notion that the lived experience of a disabled artist may directly contribute to pushing the boundaries of literary aesthetics.

In terms of the hierarchy of disability and non-normative bodies/behaviours, the manifestation of my impairment is what writer and disability activist Stella Young would describe as ‘vanilla.’ I am perceived as more acceptable, more palatable to the mainstream. I have the privilege of education, I’m articulate, white, middle-class. Nonetheless due to my lack of mobility and how I move about, my body is inscribed as deficient or inadequate. People in the street offer me their prayers, complete strangers often surprise me by asking, ‘What is wrong with you?’ Many buildings and venues are now inaccessible to me. Parking is difficult to find close to where I want to go. Traditional work spaces and hours do not fit my energy levels or my physical requirements. So, finally, I have begun to understand disability as a social construct. I am still learning but I now realise that people who do not physically or mentally function according to the dominant and very narrow concept of the normalised individual are rendered unruly, unimportant, beyond civil, invisible, asexual. We are largely disabled not by impairment or our embodied differences but by the social and attitudinal barriers that we experience.

In terms of the hierarchy of disability and non-normative bodies/behaviours, the manifestation of my impairment is what writer and disability activist Stella Young would describe as ‘vanilla.’ I am perceived as more acceptable, more palatable to the mainstream. I have the privilege of education, I’m articulate, white, middle-class. Nonetheless due to my lack of mobility and how I move about, my body is inscribed as deficient or inadequate. People in the street offer me their prayers, complete strangers often surprise me by asking, ‘What is wrong with you?’ Many buildings and venues are now inaccessible to me. Parking is difficult to find close to where I want to go. Traditional work spaces and hours do not fit my energy levels or my physical requirements. So, finally, I have begun to understand disability as a social construct. I am still learning but I now realise that people who do not physically or mentally function according to the dominant and very narrow concept of the normalised individual are rendered unruly, unimportant, beyond civil, invisible, asexual. We are largely disabled not by impairment or our embodied differences but by the social and attitudinal barriers that we experience.

I seek out like-minded disabled artists and writers, especially writers who situate disability within the wider contexts of power, as well as the every-day. I am not interested in reading inspirational stories where disability is framed as a tragedy that is overcome, with a smile, a bit of determination, and courage.

Disability has started to inform content in my writing. I incorporate my experiences and politics as a disabled woman into some of my narratives. I write about discrimination, medicalisation of my body, about pain, about the way I negotiate spaces. But how my experience of disability may contribute to the aesthetic of my artistic output is difficult to determine.

Recently I attended a Sydney Arts management Advisory Group event, an interview with UK artist Claire Cunningham. She spoke of her special relationship to the ground. I, too, focus on the ground, feeling it with my walking stick, testing, looking for unevenness, holes, anything that could cause me to trip. Because I’m weak, and my balance and coordination are not great, I use my hands a lot. I touch everything — dirty walls, toilet seats, hand rails — so dirt and scatological imagery may become part of my aesthetic. There is a sense of crookedness, of wobbliness, some muscles overworking, compensating for other muscles that are not functioning. I’m skew. My body image from a very young age has been affected by atrophy, and perhaps this too influences my creative process. I have not until now been conscious of this possibility.

Of course language is never neutral. I have in the past used language that I now realise contributes to oppressive discourse and practice. My experience of disability has made me more aware of the words I choose. I interrogate metaphors and other forms of speech more rigorously. Disability as metaphor — blind, deaf, cripple, mad metaphors — create problems for understanding the specifics of our lived experience. The challenge is to encourage nuance and experimentation, politically-accountable uses of metaphor that make people think more deeply and enable them to imagine alternatives to what exists.

I’m not sure why it took me so long to come to my current understanding of disability, why I had to experience disability personally before I even began to consider ableism. I’m not sure why our society has such a fear of physical, mental, behavioural differences. I’m also unsure of how my experience of impairment affects the aesthetic of my writing. These are subjects I would like to explore.

I seek more writing that expresses the realities and variations of human experience – gendered, racialised and disabled bodies. I look forward to aesthetics driven and influenced by the lived-experience of disability. Critically engaged and nuanced, this kind of writing can only enrich and extend our cultural landscapes.

This is a wonderful post. Thanks so much for articulating the experience so clearly. I’m becoming more and more aware of how much our personal “cultures” inform our experience of the world and yet how the dominant culture can take over in our expression of it. A simple example for me would be how aware I am of women’s inequality and yet I will still often involuntarily smile/laugh at a joke against women. The dominant culture is SO pervasive.

(BTW I use the term “personal ‘cultures'” instead of the more obvious “experience” because I think our individual experiences can create a culture about how we view the world. Your description of how your experience results in your different relationship to the ground, your dependence on tough, is a great one.)

Your point that “We are largely disabled not by impairment or our embodied differences but by the social and attitudinal barriers that we experience” makes a great deal of sense too. I think for most/many people it’s not wishing to be cruel but it’s fear, anxiety, embarrassment about how to talk to others whose lives are so different that is the problem (at least at the personal level. The socio-political level is a different matter.)

I have become aware of your comment thanks to Amanda Tink’s tweet of the article in her #AusDisLit posts. Thank you for contributing to the discussion. I too find the term ‘lived experience’ problematic for a number of reasons. I like the idea of personal and group cultures as representing at least part of our experience. Apologies for the 5 year delay in responding 😊

Haha that’s ok Gaele. As a guest poster, I guess you weren’t to know that there had been comments. It’s never too late – I love that you came back when you discovered the discussion.

I really enjoyed your article. I love the sentence “the manifestation of my impairment is … ‘vanilla'”. Your commentary in this area is really valuable, and desperately needed, as I too think the ‘inspirational’ story doesn’t get us very far. Please, keep writing!

Thank you for contributing to this discussion and for your encouragement 😊