by Bill Holloway

Brent of Bin Bin made a stir in the 1920s and thirties when ‘his’ family saga of life in the High Country of southern New South Wales came out. Altogether, six books were published under that name, without Brent’s identity, although often accurately guessed at, being known for sure until the 1960s.

Brent of Bin Bin made a stir in the 1920s and thirties when ‘his’ family saga of life in the High Country of southern New South Wales came out. Altogether, six books were published under that name, without Brent’s identity, although often accurately guessed at, being known for sure until the 1960s.

Miles Franklin (1879-1954) was probably almost in despair as a writer when she made the decision to publish under the pseudonym Brent of Bin Bin. By the late 1920s she was nearly 50 years old. The ground-breaking My Brilliant Career she wrote as a teenager had come out in 1901 to great acclaim and popular success but the intense scrutiny it brought upon her family and neighbours had led her to withdraw it from re-publication. Her next two novels,The End of My Career (1902) and On the Outside Track (1903), brilliant attempts to explore the relationship between ‘real’ and fictionalized life were rejected by her publishers. Following them, Some Everyday Folk and Dawn (1909) met little success and her next, The Net of Circumstance (1915) under the silly pseudonym Mr. and Mrs. Ogniblat L’Artsau, none at all. And since then there had been nothing.

Born into the squattocracy, Australia’s landed gentry, she had been dragged down by her father’s unwise venture into farming, and her parents’ failure to secure her a decent education. After some years working with the women’s trade union movement in America, before moving to England during WWI and seeing war service in Serbia, she had been barely clinging to the bottom rungs of the lower middle class in England during the Depression doing clerical work and writing in her spare time. With the mss of at least four completed and unpublishable novels ‘under her bed’ she made the no doubt unpalatable decision to tone down the feminism and experimentation in her writing and to adopt her topics to mainstream taste – family sagas of the Australian bush. In other words, she decided to man up, and how better to do that than to adopt a male nom de plume.

In 1900 Franklin had written to Blackwoods, the publishers of My Brilliant Career:

Please on no account allow “Miss” to prefix my name on the title page as I do not wish it to be known that I’m a young girl but desire to pose as a bald-headed seer of the sterner sex.

That wish had been thwarted by Henry Lawson’s description of her in his Preface as “just a little bush girl, barely twenty-one” but now she was in control and the secret of Brent’s real identity, known only to herself, her best friend Mary Fullerton and a smallish circle of family and friends, although guessed at by half the industry, was still being kept beyond her death in 1954, so that Marjorie Barnard in her biography published in 1967 could only point to the clear similarities between Franklin’s and Brent’s work as proof that they were one and the same.  In fact ‘Bin Bin’ was the name of a station (large grazing property) belonging to Franklin’s father’s family which she used for the first time in My Brilliant Career (“My father was a swell in those days – held Bruggabrong, Bin Bin East and Bin Bin West, which three stations totalled close on 200,000 acres”).

In fact ‘Bin Bin’ was the name of a station (large grazing property) belonging to Franklin’s father’s family which she used for the first time in My Brilliant Career (“My father was a swell in those days – held Bruggabrong, Bin Bin East and Bin Bin West, which three stations totalled close on 200,000 acres”).

Further, her deception of her publishers, Blackwoods, was double or even triple, as she not only acted as Brent’s agent under the pseudonym Miss S. Miles or Mills, later clarified as Sarah Mills [her real full name was Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin], but also claimed that the author was ‘William Blake’, a member of an old Australian squatting family who wished to be known as Brent to distinguish him from the Romantic poet of the same name who had died a century earlier.

Early in 1927 ‘S.Miles’, as agent for Blake, submitted a draft of Up the Country, ‘a Novel of the Australian Squattocracy’ to Blackwoods. Their prompt acceptance included the right of first refusal on the next two or more works. In June, Franklin returned to Australia, to care for her ageing parents in Carlton, Sydney, and began typing out the final draft in the Mitchell Library. Over the space of a few months of amazing productivity Franklin knocked out Up the Country, the first draft of Ten Creeks Run and began working on Cockatoos, a rewrite of the unpublished On the Outside Track as the third novel in a family saga based loosely on the arrival and establishment of her mother’s family in Australia over 3 or 4 generations.

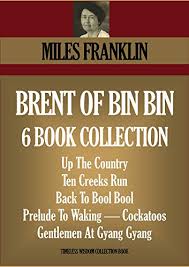

In all, six novels appeared under the Brent of Bin Bin name, following the Mazere, Labosseer and Poole families and all their connections. They are:

Up the Country (1928) Period 1840s-1860s. First generation

Ten Creeks Run (1930) Up to the 1890s. Second generation

Cockatoos (1954) Boer War to 1906 (‘A Tale of Youth and Exodists’)

Prelude to Waking (1950) 1920s Mayfair, London

Gentlemen at Gyang Gyang (1956) 1920s, back in the NSW high country

Back to Bool Bool (1931) late 1920s (the return of a new generation of ‘exodists’)

Blackwoods brought out Up The Country, Ten Creeks Run and Back to Bool Bool in fairly short order as a ‘trilogy’ to good reviews and moderate sales, but there things stalled. The Depression made all business difficult; Prelude to Waking, a Mayfair comedy originally written in 1925, which Franklin was obstinate in wanting published next, is very different stylistically to the other five books in the series, and shares no characters or families with them; and then there was the War (WWII).

The most prominent of the initial reviews was in the Bulletin of 2 Jan 1929. Headed ‘An Australian Classic’, the review said that although Brent had no style as understood by literary cliques it contained some of the most tender writing in Australian literature (Roe, p.301). Likewise, HM Green writing later said, “The Bin Bin books are not works of art, but extracts from life or stories of life.”

After the War, Beatrice Davis of venerable Australian publishers Angus & Robertson (who famously had refused My Brilliant Career back in 1900) purchased the rights from Blackwood and over the course of half a dozen years, brought out all six, starting with Prelude to Waking in 1950 and reissuing Up the Country in 1951. Unfortunately, Miles Franklin did not live to see the publication of the final book in the series which she had been writing, re-writing and tirelessly promoting for a quarter of a century.

Meanwhile, during the period of her initial success as ‘Brent’, Franklin had published under her own name Old Blastus of Bandicoot (1931), similar enough in style and location to reconnect her with the public who had not forgotten My Brilliant Career (To coincide with the release, Nettie Palmer published an important essay comparing Franklin with South Africa’s Olive Schreiner)*. She followed up with a forgettable murder mystery in the style of Dorothy Sayers, Bring the Monkey (1933) and then her popular triumph, the Prior Prize-winning All That Swagger (1936), a saga based on her father’s family and very much in the style of Up The Country. According to one of the judges, “In not one page is there to be seen any evidence of overseas influence. Only an Australian could have written it, and there has been nothing written like it except the Brent of Bin Bin novels.”

Miles Franklin’s best/most innovative writing was done when she was young – My Brilliant Career, The End of My Career/My Career Goes Bung and On the Outside Track/Cockatoos. Her ‘middle period’ as she struggled with the opposing ideas of sexuality and purity – for men as well as for women – resulted in some pretty well unreadable books, including Prelude to Waking. Her conversion to Bush Realism – she claims that she and Steele Rudd founded the ‘Pioneer’ school of writing – beginning with Up the Country, allowed her to write freely once again, without too much in the way of plot, just stuff happening, in the high country that she loved.

The books are all available as ebooks on Amazon but if I were rich I would reissue the five connected Brent of Bin Bin books (not Prelude) as a boxed set and I’m sure with a bit of advertising (and a movie deal?) they would regain their rightful place at the centre of Australian Bush writing. .

*Nettie Palmer’s essay ‘The “Olive Schreiner” of Australian Literature’ was published in the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail, 16 June 1932 (Roe, p.331) and has been republished by Vivian Smith.

References:

H.M. Green, A History of Australian Literature, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961

Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin, Fourth Estate, Sydney, 2008

Sylvia Martin, Passionate Friends, Onlywomen Press, London, 2001

Marjorie Barnard, Miles Franklin, Hill of Content, Melbourne, 1967

Vivian Smith (ed.) Nettie Palmer: Her private journal “Fourteen years”, poems, reviews and literary essays, UQP, St Lucia, 1988 (here, p.419 on – follow link to download pdf)

Prior Prize announcements, 1936 (here), 1939 (here)

see also: The Australian Legend, Miles Franklin page

Bill Holloway, the author of this essay, blogs at The Australian Legend. He is an old white guy the subject of whose (very) mature age M.Litt thesis was ‘The Independent Woman in Australian Literature’.

Great post Bill. It reads really well. What a career.

I’m amused by the “The Bin Bin books are not works of art, but extracts from life or stories of life.”

I’ve read a few newspaper articles over the years discussing who Brent of Bin Bin was, most, of course, identifying Miles Franklin. But what a hoot is that other pseudonym, which I see reverses her old home area – (Austral) Talbingo. Ogniblat is great.

I have still yet to read Brent of Bin Bin, but I like your idea of publishing the connect ones as a set.

One day I will get to the Mitchell and read The Net of Circumstance. Though – hint to our archivist! – it’s out of copyright of course and I would love to see it and also MF’s unpublished novels – from the Oginblat period probably, which get a brief mention here as mss under the bed – short fiction and journalism in the AWWC archives.

The most important of her journalism, from during WWI are –

Ne Mari Nishta: Six Months with the Serbs (1918)

How the Londoner Takes his War (1916) by Dissenting Diarist

All of that journalism in particular interests me.

Me too. I should be able to find Ne Mari Nishta, I have links to essays about it. But the Londoner one is a total of 20,000 words, I think, published in Australian newspapers but we need to know what penname she used.

All these writers and their multiple pennames!

Excellent post Bill. Every time you write about Franklin, I come away wanting to read more about her life and try more of the Bin Bin stories in particular.

I went to a staged reading performance on the weekend at the State Library (which is one of the 3 possible venues I may have picked up Covid from this weekend!) about Franklin called Her Brilliant Career (written by Alice Spigelman).

I had planned to write up something about it on my blog, but the woman sitting next to me was wearing an overwhelming amount of perfume that was like a force field around her, almost suffocating and instead of writing in my notebook, I used it to fan myself the entire time. By the end of the reading I was so befogged and het up I couldn’t stay for the Q&A with the playwright, I had to flee.

I then spent the rest of the weekend fuming about my enjoyment of a play being ruined by inconsiderate perfume usage (if you must wear perfume, the scent of it should tantaslise and tease, not knock your neighbour out!) rather than thinking about what I actually saw & heard.

And now Covid…

By the time I found time to respond to your comment I see you have overcome perfume induced brain fog and written a review of the play.

(What if the Covid was riding on the perfume!)

I’m glad I keep you interested in MF, she lived an interesting life and was an innovative writer.