“The other stories are very sentimental, but are not uninteresting, and are nicely told.”

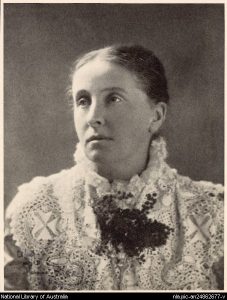

Review of At Midnight, and other stories by Ada Cambridge (1897).

Lord Thomas de Bohun had been married twice—and more. In fact he was sick and tired of womenkind. And that is why he came out to Australia. He thought a year or two of travel in a savage country, free of all the trammels of civilisation, would give him a rest. Besides, the second Lady Thomas had been rather nice to him, and she had died pathetically, and he missed her. Wherefore he loathed the British matchmaker for the present, and was glad to get as far away from her as possible.

He was not a roué and a reprobate, such as this introduction might imply. Nothing of the sort. A better-natured or more charming young man—he was on the right side of forty still—was not to be found in London. But he was the son of a duke, poor fellow, with a great deal of money, and no work to do—misfortunes for which the fair-minded reader will make a large allowance.

In the beginning, Australia did not quite answer his expectations. Whereas he had imagined a dress-suit to be a thing unknown, he found himself obliged to wear one nightly, and he was just as ducal in our city clubs and drawing-rooms as he would have been at home—indeed, a great deal more so. But as soon as he escaped into the country he was all right. Clad in moleskins and a Crimean shirt, with a soft felt hat on his head, and big spurs on his heels, he galloped about at kangaroo huts and cattle musters, a simple bush-man of the bush (while his servant played the gentleman in Melbourne), enjoying health and happiness and the unrivalled charm of novelty to a degree unknown before. Anybody could get him who had no right to get him. The great country houses, flattering themselves that they alone could entertain him suitably, found it a most difficult matter to drop salt on his elusive tail.

He was at a bush hotel one evening, spending a convivial hour with perfect strangers who did not know he was Lord Thomas. Having heard his name was De Bohun, they called him Mr Bone, and were quite satisfied with that. So was he. The talk turned upon agricultural machinery, as used by English and Australian farmers respectively; and a member of the latter class, as Lord Thomas supposed, was most anxious to show him a five-furrow plough and various modern implements—American “notions” of the labour-saving kind.

“You come home with me,” said the jolly old man, “and you shall see ’em working. Now do, Mr Bone. Pot-luck, you know, but a hearty welcome.”

Lord Thomas jumped at the chance, for, amongst other delightfully novel pursuits, he had set himself to the improvement of his mind in these matters, as a responsible landlord and potential duke.

“But your family?” he objected. “Would it not inconvenience them to receive a stranger without warning, and at so late an hour?”

“Not a bit of it, Mr Bone. There’s always a bed ready for anybody that may turn up. Mrs Kemp will be charmed to see you.”

“In that case,” said Lord Thomas, “I accept with pleasure.”

A pair of rough horses, in a ramshackle American wagon, were brought round, and they set forth on a ten-mile voyage through the bush, with neither lamps nor moon to steer by. At a long, swinging trot, never hastening and never loitering, the shabby animals did it in an hour without making a false step, and were as fresh at the end as at the beginning. The mysterious, illimitable gloom and the romantic solitude were very refreshing to the London man, and so was his host, who was full of merry tales and valuable information. Lord Thomas, in short, enjoyed the adventure thoroughly.

But he was taken aback by the sight of Mr Kemp’s house. Instead of the shanty of his anticipations, he beheld a tall and imposing structure, cutting a great block out of the starry midnight sky. A sweet place by daylight—ivied, virginia-creepered, grape-vined all over its mellow brick walls and decaying verandahs, with a great garden and magnificent trees around it.

“Built by my father in the early days,” said Mr Kemp. “The first big house in this district, and the only one for nigh twenty years. We’ve been rich folks in our time, Mr Bone, but the ups and downs, you know—things ain’t what they used to be, especially since the Boom. However, we’ve still got a roof over us, thank God, and a crust to share with a friend.”

The family had retired, and the guest, having been warmed with whisky, was escorted to his bedroom by his host. It was a kind of bedroom to make him feel slightly nervous about meeting his hostess next morning. The bed creaked with age, and so did the carpetless floor beneath it; but the linen was fine and the pillows soft, the handsome old rosewood furniture shone like glass, and there was an impalpable air about everything that bespoke the house of a lady.

“I don’t know whether you like the windows shut?” said Mr Kemp, hospitably bustling about. “We always keep them open, and the blinds up. Nobody to over-look us here, you know.” He tried to pull down a sash which stuck in the frame, but at Lord Thomas’s request desisted.

“Leave it as it is,” said the guest. “I like them open. It’s so Australian!”

And he presently lay down on his lavender-perfumed couch, feeling—after his experience of bush inns—that it was the nicest bed he had ever occupied. And that scent of the earth and of the night, coming in through open windows, how exquisite it was! He blew out his candle—a home-made candle in an old chased silver candle stick—and slept like a baby.

Not for long, however. Voices called him through those open windows, and before six o’clock he was leaning out of one of them, awake and alive as he had rarely been at such an hour.

What an Arcadian world was this, in which he felt like a man new born! Air as clear as crystal and dew shining on shrubs and trees; giant acacias and native white cedars, and pink and white oleanders that could have swallowed an ordinary bush house; the morning moon still gleaming like a jewel over the saffron sunrise and the intensely dark-blue hills. He had heard curlews in the night, and frogs at the break of dawn; now the magpies were fluting all over the place, cheerful fowls were crowing, laughing jackasses shouting “Ha-ha-ha!” and “Hoo-hoo-hoo!” to one another. Delicious sounds! But none so acutely audible as the immense silence at the back of them.

“This,” said he to himself, “is the real bush, that we have heard so much about, at last.”

He looked down from his window, and saw the sparrows at the ripe grapes now loading the eaves of the verandah; saw a hare limping along the gravelled paths, where no hare should be. He looked over the garden hedges to the peaceful field outside, where cows were feeding quietly, throwing shadows on the wet grass; flocks of cockatoos were screaming amongst them, and sprinkling themselves like white flowers over the fresh-ploughed land; and an army of dusky jays held the vineyard on the hill, whence their joyous gabble rose continuously. It was not his property they were destroying, and he saw and heard them with delight—those denizens of the wild bush that was healing him, body and soul, of the ills of excessive civilisation.

The pink dawn spread and glowed, quenching the horned moon and dimming the sapphire hues of the distant ranges. Then some white bee boxes gleamed conspicuously to the right of the flower garden—an orderly encampment, like tents on a field of battle—and he could see the busy swarms going forth to their day’s labor. He could even hear them humming, they were in such myriads. And another thing he heard—a faint, muffled clatter—which he traced to a little building near the gate of the bees’ enclosure; a shed made of reeds, with two windows and a door in it—doubtless the honey-house, in which some one was early at work. As he listened to the noise within, he watched the door, which faced his view, and presently he saw a girl come out of it. She wore a pink cotton sun-bonnet, veiled with a bushman’s fly net, and as an all-embracing tight apron, which made her look like the toy figures of a Noah’s ark. In each hand she carried a long tin box, one heavier than the other, by rough loops of fencing wire; and she marched with them down an alley between the bee hives. Mr Kemp had casually mentioned his daughter, who, at the time, Lord Thomas had not regarded as affecting him in any way. Evidently this was she, and the circumstances of the house disposed him to take another view of her.

He saw her put the boxes on the grass and set the lids open, then lift the roof from one of the wooden hives. A cloud of angry insects rose to her stooping face and buzzed about her; it made him tingle to see them, but she heeded them no more than if they had been motes in the sun-rays that now lighted up her figure so effectively. She puffed something that smoked into the hive from a sort of bellows arrangement, and then lifted out the frames of comb, held them dangling in the air while she brushed black masses of bees off them, and placed them edgewise in one of the boxes on the grass until she had quite filled it. Out of the other she took similar frames, which she dropped into the emptied chamber, and shut down there. Then he saw her laboring towards the honey house with the weighted box, and was exasperated to note how it dragged her down. She passed it from hand to hand to case the strain, but could not carry it without a twist of her supple body, a staggering gait, and pantings that he seemed to hear, though of course he could not.

“What a shame!” he inwardly ejaculated. And he withdrew into his room, emptied a can of water into a battered old bath, and dressed in haste. The clatter in the honey-house, which had ceased while she was amongst the bees, showing that she worked single-handed, began again.

“I wonder,” quoth Lord Thomas, “what she’s doing in there?”

He thought he would go down and see, and went, stepping softly, so as not to disturb the rest of the family, who did not seem to rise so early as she. As usual in the bush, no locks or bolts impeded him; he turned the handle of the hall door, and noiselessly slipped out.

What a morning indeed! Freshly autumnal for it was the end of March—though the day would be all summer until the sun was low again; cool almost to coldness, with an air that washed the lungs and invigorated the heart in a manner to make mere living an ecstasy—even to a lord—the air of the spacious, untainted bush, and of nowhere else in the wide world. He stood a moment on the steps of the verandah to drink it in—to sniff the wholesome odor of gum trees and the richer scent of the perennial orange flower starring the thick green walls of the orchard paths. Then he strolled down one of those perfumed lanes—the one that divided the back garden from the front—and presented himself at the gate of the bee enclosure just as Miss Kemp, with one of her tin boxes, dashed out of the honey house and slammed the door behind her, disappointing the expectations of a cloud of besieging bees.

She saw him and stopped short, evidently taken aback, and conscious of her coarse apron and limp sun-bonnet, not worn for company. He hesitated for a moment in sympathetic confusion, but, being immediately aware that the form thus plainly outlined was a charming one, as also the pink face in the frame of pink calico, stood his ground and modestly accosted her. He lifted his cap gracefully, and a bee got under it.

“Good morning—you brute!” was what he said.

“Don’t come,” she cried in answer, waving him back. Then she pulled off a sticky glove and held a bare hand over the gate, regardless of bees, expressing a polite astonishment fit his being up so soon.

“I heard of your arrival, Mr Bone.” said she. “I hope you slept well. I hope you like Australia, as far as you have seen it.”

They chatted conventionally for some minutes. He apologised for his presence, and she reassured him, on behalf of the family with an easy frankness that seemed to say he was but one of dozens of Mr Bones flowing in a continuous stream through the house, like tramps through a casual ward. And then he begged to be allowed to help her in her work. “ I am sure,” said he, “you must want somebody to carry that heavy box—oh, conf—! They know I am a stranger, evidently.”

“Go away,” she laughed. “You have no business here. I don’t want help—I am quite used to doing it all—and you’d better go and sit on the verandah, where you can be at peace. Or wouldn’t you like a stroll round? With a pipe, perhaps?”

“Will you show me round?”

“I’m sorry I can’t; I must be busy here. The honey is coming in so fast this weather—which may break at any moment—that I can’t gather it quickly enough. I get on an average nearly a quarter of a ton per day.”

She looked at him with an air of professional pride, forgetting her costume; and he looked at her. The closer view showed freckles and a retrousse nose, without at all detracting from her charm. He could gaze full into her face without being rude, because her eyes were continually following the movements of the bees that buzzed about him. Every now and then her fingers skirmished round his head like a flight of butterflies.

Five minutes more and she was tying a large apron round his waist, over a very old coat that did not fit him, and he was planting on his aristocratic head an aged straw hat, flounced with mosquito netting. In this costume, finished off with a pair of good gloves of his own, cheerfully sacrificed, he was allowed to pass through the gate and take up the box by its handles of fencing-wire. The sun was well above the ranges now, and every dewy leaf and blade of grass glittering.

“What a heavenly morning!” he sighed ecstatically.

“Isn’t it?” she assented, and then fell to work again with an energy interesting to contemplate in a person of her sex and years. She walked between the rows of hives till she came to the one to be operated on; he walked after her, inwardly nervous, but with an air of utmost valour.

“Now be careful,” said she, as she seized her little bellows. “Tuck that net into your waistcoat in front, and then lift the lid off for me.”

He did as she bade him, and gasped at the spectacle presented. How all those bees managed to breathe and move, let alone work, in the space they occupied, was more than he could understand. She had no time to explain just now. While he stood rigid, and imagined bees under the hem of his trousers—for they were thick in the grass he stood on, she rapidly smoked the hives and drew out the frames of comb, heavy with honey, brushed thousands of stinging things off them, and placed them in the empty tin. From the full ones she took the frames, filled only with hollow cells, which she had brought from the honey-house; and these she dropped into the hive amid the masses of bees, leaving less than an inch between one wall of comb and another.

“And you make the same wax do?” he inquired, thirsting for knowledge.

“Many times,” she replied, pleased to inform his ignorance. “That comb will be re-filled in about ten days. Put the lid on again, please. Gently—don’t crash more than you can help. Now—”

She straightened her back and looked at him.

“Now what?” he inquired eagerly.

“Well, if you would, you might be filling the other box while I extracted.”

But this was rather more than his courage was equal to. He said he was afraid he did not know enough about it, yet.

“Very well; we will go and extract the lot we have.”

They went to the honey-house together, and she quickly shut the door as soon as both were in. He smiled to himself, as he saw her do it. The situation to him was—well, noticeable; to her it was absolutely without sentimental suggestions. The honey-house was the place for work, not for play.

It was a stuffy and a sticky place, for its little windows, as well as the door, had to be closed to keep the bees out. Ventilation depended on the loosely-woven canvas lining the reed-thatched walls. Half of the floor was raised above the other half, so that the honey from the extractor, pouring from the spout upon a fine sieve, could flow downwards to the great tank, and from that into the tins which conveyed it to market. Five tons’ weight of these tins were stacked on the lower floor, all filled and soldered up; and many more, Miss Kemp stated, were stored in the house.

“I used to get sixpence a pound for it,” she informed him, with an anxious, business look in her pretty grey eyes; “but now the stores won’t give more than three pence. It really doesn’t seem worth while, at that price, taking railway charges and all; do you think it does?”

Lord Thomas did not, emphatically.

“So I am going to try exporting. I have the regulation boxes and tins—fifty-six pounds in a tin, and two tins in a case—and, as soon as I can get my hands free here, I shall prepare a consignment for the London market. I do hope that will pay. You are an Englishman, Mr Bone—what is your opinion of the chances of a trade in Australian honey?”

With the confidence of utter ignorance, Lord Thomas assured her that there was a splendid opening. He knew people—heaps of people—who would snap it up gladly; and proposed to himself to be her purveyor to those people, comprising all the de Bohuns and his numerous lady friends.

“Oh, I am so thankful to hear you say that!” Miss Kemp ejaculated, with a heave of the chest. “You see wool is down, and cattle selling for nothing, and the value of places like this dropped to less than what they are mortgaged for; therefore something must be done. I’ve begun with honey, so I want to go on with it. I can increase to any extent, if I can only get a regular and paying market.”

He was oddly touched, and more interested and amused than he had ever been in his life, to see a pretty girl regarding her destiny from such a point of view. It was something quite out of his experience. She really wanted to work, and not to flirt—to do something for men, instead of being done for by them. And yet there was nothing of the new woman about her. She was sweetly old-fashioned.

For instance, it gave her a visible shock to learn, in the course of miscellaneous conversation, that he had a baby ten months old and had left it behind in England.

“What!” she exclaimed tragically, “without either father or mother to look after it?”

“Oh,” said he, “there are plenty of people to look after it.”

“Who will—who could—like its own parents?”

“Well, you wouldn’t have a fellow travel about the world with a nursery in his train;—now would you?”

“I don’t know how you can travel, under such circumstances.”

He thought this very funny. And yet he liked it. Lady Thomas the first had detested children; Lady Thomas the second, a mother for a day, had shown no feeling for them. This girl’s evident concern for his virtual orphan—who, as she said, might die of croup or convulsions without his knowing it, while he idly gadded about like an irresponsible bachelor—struck him as very interesting. She asked questions about it in an earnest way, and made him feel quite fatherly and serious. He wondered if the poor little brat was really being cared for properly, and determined to make strict inquiries by the next mail.

Conversation was not allowed to hinder business. While she talked in this friendly, human fashion, Miss Kemp worked as he had never seen a lady work before, as he had never worked himself since he was born. With a frame of comb in one hand, and in the other a big knife, kept hot in a tin of water standing on an oil-fed flame, she seared off the capsules from the cells that had been filled and closed, leaving those that had bees in them, with the rapidity and dexterity of a performing conjuror. Then she dropped the frames into the wheel arrangement inside the extractor, and turned the handle violently— no, he turned it for her while she prepared more frames—full ones for the machine and empty ones for the tin box, and cleared up the shreds and wax, and so on. She had no regard for attitudes, nor the state of her complexion, and it was clearly evident that she valued Lord Thomas for his services and not for himself. He had never been in such a position since he was a fag at school; in relation to a woman, never. It chagrined him a little, but pleased him much. He determined to remain Mr Bone for the present.

Called to breakfast, he made the acquaintance of just such a hostess as he had expected—a faded woman, with a refined face and voice, English born, and homesick for her own country. He exercised upon her that art of pleasing, of which he was a master, and she was so charmed with him that she begged him to stay a little—not to run away immediately, unless bored by the dulness of the place. Her husband abetted her, with the unquestioning hospitality of the bush, which asks no more of a guest than that he shall know how to behave himself.

“And I’ll show you all my improvements,” said Mr Kemp. “A good deal more than you could run through in an hour or two, or even in a day.”

“Thanks, thanks,” Lord Thomas murmured. “Just at present I am more interested in the honey industry than in anything else. I intend to keep bees myself when I get back, and it is a great chance for me to see all the working of the thing as it is done here. Er—er—how clear and beautiful that is!” He looked at a dish containing a square block of honey in the comb, neatly removed from the wooden frame it was made in. Letty hastened to pass it to him.

“Isn’t it?” she crooned, surveying it with a maternal air. “And this is what I get only threepence for in the local market. I can’t but think there must be ways of exporting it in sections, with careful packing. Don’t you think if it could be brought on English breakfast tables in the comb like this there would be a great demand for it? I am sure they haven’t honey to surpass our honey.”

Lord Thomas was equally sure of it— convinced indeed, that benighted England never tasted anything like it in its life. Mrs Kemp smiled a superior British smile. Mr Kemp pooh-poohed the fuss his daughter made over comparative trifles. What was honey, as a topic of interest for an Englishman anxious to improve his mind, compared with ensilage, and irrigation, and six-furrow ploughs.

For two precious hours Lord Thomas found himself obliged to attend to these two latter subjects with what interest he could muster, and he only got away from them so soon by force of misleading insinuations to the effect that bees were his natural hobby and bee-keeping his proposed profession. At eleven o’clock he resumed his sticky apron and gloves, his old coat and his veiled old hat, with more delight than he had ever taken in clothes before— ridiculous as it seemed, even to himself— and rushed to the heated and messy honey-house as he had never rushed to a royal garden party.

Letty’s hot face lighted up at sight of him. Beads of perspiration lay like dew under her clear eyes and over her pretty lips, but she cared not, neither did he. This sort of thing did not spoil the effect, as usual.

“Oh, how good of you,” she exclaimed. And at once she set him to work. He buckled to with might and main, as if his life and hers depended on the amount of honey they could extract in a given time. They had two hours together, talking while they worked, growing better friends every minute.

“Labor-saving machines,” said she, still harping on the one string, “are splendid, I know, but they run away with money when there isn’t any money. My plan is just the opposite of father’s. It mightn’t be such good economy in other circumstances, but as things are it is my idea of economy. I don’t know what you think.”

He told her what he thought, and she told him it was beside the point. So it was. So he wanted it to be. Hard as he worked at the handle of the extractor, he worked still harder at trying to change the subject. But, though she might be led aside a step or two, she could not be wholly drawn from it.

It was worse after lunch. She said to him, with the firm air of a general directing military manoeuvres, “Now you know all that is to be done in the house, so you can attend to that while I am changing the frames in the hives. Oh never mind the box; I can carry it quite easily. And we shall get on twice as fast.”

He found he had to do it—the uncapping with the hot knife, and all the rest of it—while she went back and forth outside. It was a long afternoon, and the little shed was stifling. The perspiration poured from his brow and trickled down his neck as he strained every nerve to be ready for her each time she brought the full box in. And his wages were next to nothing.

But at last the sun went down, and his long struggle to get the better of his rivals seemed over. They came straggling home in the golden twilight to their well-earned rest, and Letty Kemp prepared to follow their example when it was too dark to work any more.

“There,” said she, with a sigh of utter weariness and satisfaction, “we have done well, haven’t we? I can’t tell you how much obliged to you I am, Mr Bone.”

Suddenly he felt tired of being Mr Bone and a casual labourer, so he said awkwardly, “ Er—er—I think you haven’t got my name quite correctly, It is De Bohun—Thomas de Bohun.”

“Oh, I beg pardon,” she returned, in an airy manner; and he perceived that she was not enlightened. “You know, Mr de Bohun, that there is a little talk and movement about eucalyptus honey just now. Some chemist people at home have been praising its medicinal properties. And it is everything in these cases to strike while the iron is hot.”

“ Ye-es,” drawled Lord Thomas absentmindedly. Actually she had been so absorbed in those blessed bees as not to have heard of him in his proper character.

They took off their sticky overalls and returned to the house to prepare for the evening meal. And when Miss Kemp came downstairs, washed and brushed, in a pale-blue frock, a white muslin fichu, and a rose, Lord Thomas thought her beautiful. Yes, in spite of freckles and a turned-up nose. Never had he seen in woman’s shape such pure health and such an absence of self-consciousness. Of all the charming novelties surrounding him, these were the most charming.

“I suppose she’s too busy to notice what a sweet creature she is,” he thought, as he sat down to the juicy slice of mutton for which he had earned so keen an appetite. And he anticipated with joy the leisure hours he now expected to spend with her, undisturbed by bees, in the somewhat threadbare drawing-room.

All went thither together at the conclusion of the meal—the comfortable tea-dinner of the bush. Mr Kemp, desiring to talk ploughs and ensilage, proposed a smoke. His guest, yearning for tobacco, aching in every limb, declined. Mrs Kemp sent her daughter to the piano, and Letty played—admirably Lord Thomas thought—the intermezzo from Cavalleria, and a few things of that sort; and while he tried to listen, and to feed his sense of the girl’s many-sided excellence, his hostess babbled about London as she remembered it, and wanted a thousand and one details of the dear city as it was now. During laborious description of the Thames Embankment, Letty rose from the music stool, and softly moved about the room. Her admirer flattered himself that she was listening to him, but was shortly undeceived. She vanished at a moment when his face was turned from the door, and never came back.

“Does she actually leave me!” he dumbly groaned. “Is she so lost to all the feelings of her sex as to imagine that I won’t miss her while I have this old woman to talk to?” It was enough to drive any titled gentleman to extremities.

Soon he was hunting the dim verandahs round and round, in search of the fugitive. He explored the passages of the house; he walked about the garden, smelling so strongly of orange blossom, in the pure night air; and he used bad language under his breath. At last he was drawn to a light shining like a thread of incandescent wire through a certain out-house door. He lifted the latch and looked in.

There she was. Kneeling on a piece of sacking in the middle of the floor, with her blue skirt pinned up around her waist under a large apron, and with all the mess of a station workshop and lumber-shed around her, she was busily engaged in painting her brand on honey tins. A kerosene lamp shed effective rays on her dainty figure, her fair clear skin, her shining chestnut hair. In short, Lord Thomas stood and looked at her, fascinated. Of the thousands of pretty women that he had admired in his time, not one had ever appeared to such advantage in the matter of background and grouping. Yet he protested at the sight.

“Oh, I say! Haven’t you done enough work for one day, Miss Kemp? Are you trying to kill yourself?”

She looked up at him with a laugh; and her eyes focussing the light, were like stars in the grubby gloom.

“Oh, I beg your pardon, Mr de Bohun! I thought, as you were talking to mother, you would not notice if I slipped away for half an hour.”

“Did you?” said Lord Thomas, entering and shafting the door behind him.

“I want so badly to get my consignment away next week. And I thought if I painted the tins to-night, they would be dry for packing in the morning.”

She continued to dab her black brush upon a slip of perforated zinc, but her quick hand became slightly unsteady, and she blushed visibly, even in that bad light. The fact was that Lord Thomas—not as Lord Thomas, but as a man—was a delightful fellow, and it was not in nature that a healthy, heart whole girl could spend a long and intimate day with him without being more or less affected in the usual way. As yet her bees were of more consequence than lovers—he was resentfully aware of it—but that did not prevent her feeling hourly more conscious that toil was sweetened by his participation therein. She was pleased that he had found her. She was more pleased when he took the black brush from her, asked leave to remove his coat, turned up his cuffs, and began to paint honey-tins himself.

“I am not a very practised hand at this sort of thing,” he confessed. “You must tell me if I don’t do it right.”

“You are quite as practised at that as I am at looking on while others do my work,” she replied.

“So I suppose,” he rejoined, thoughtfully.

They had a happy hour, unmolested by the parents, who never supposed that their practical Letty could lend herself to foolishness. Lord Thomas painted all the tins successfully. He could not well go wrong while she held the lettered label straight. Their two heads were within an inch of touching as they bent over their job; a handkerchief might have covered their four hands while the branding was in progress. They looked at each other’s fingers continually.

“Mine,” said Letty, “are quite rough compared with yours. I don’t think I ever saw such beautiful nails. It’s my belief you never did a stroke of work in your life until you came here.”

“Well,” said Lord Thomas, coloring a little, “I am afraid I haven’t done much. You make me awfully ashamed of myself, Miss Kemp.”

They fell into serious talk at this stage—the first serious talk Lord Thomas had ever had with a young lady, all his experiences notwithstanding.

“I wish,” he abruptly remarked, “you’d teach me to be as useful as you are.” There was much feeling in his voice.

She seemed to think the matter over. Then she asked him when he intended to return home. He said he was not sure.

“Soon, I suppose?”

“Oh, I suppose so.”

“You must go soon,” she urged. “You must, for the sake of that poor baby, left to the tender mercies of hired people.”

“Well,” he said, “I will.”

“Then you will have an opportunity to be very, very useful. You can look after my honey for me in London—oh!”

He flung the paint-brash into the pot.

“I suppose it is useless,” he said, through grinding teeth, “to expect you to care a straw for anything except honey and bees!”

There were but two courses open to a self-respecting man, titled or otherwise—to make her do it, or die in the attempt.

She is Her Grace the Duchess now. And an excellent duchess into the bargain. The smart folks laugh at her for not “knowing her way about,” but the duke does not. He thoroughly realises that she knows it better than they do. When, as a surprise present to her, he established a magnificent apiary in the castle grounds, and then found she did not care for it, he was a little disappointed; but he soon woke to the fact that bees had been merely the makeshift of circumstance until worthier objects for the exercise of her splendid abilities were provided. With great house-holds to administer and young dukes to rear—not to speak of a thousand matters of more public moment—she advisedly transferred her interest in honey to the wives of her husband’s tenants.

“But they will never make honey like mine,” she says, shaking her coroneted head. “It wants the taste of the eucalyptus in it.”

~

Cambridge, Ada. “A Sweet Day“, The Narracoorte Herald (25 Jun 1897; supplement): 1.

“Literature“, unsigned review of At Midnight, and other stories by Ada Cambridge (London and Melbourne: Ward, Lock, and Coy. 1897), in The Capricornian, (18 Dec 1897): 33.

Wow! Now I see why she is so popular! If only I could write as well.

Glad you enjoyed it, Sara. It has been fun finding these old stories.

I really enjoyed this story (though she took a while to get to where she was obviously going). Another development of my middle class working girl theme (250 kgs a day is an enormous amount of honey!). Mary Gaunt also advocated beekeeping as a viable occupation for unmarried women (Kirkham’s Find) and also, some decades later, Kylie Tennant (The Honey Flow)

Middle-class working girl transforming into hard-working aristo. A bit of a class kick in the idea?