by Michelle Scott Tucker

Patricia Wrightson (1921-2010) was a noted children’s author. Michelle, a childhood fan, here reevaluates Wrightson’s use of Aboriginal stories.

Patricia Wrightson (1921-2010) was a noted children’s author. Michelle, a childhood fan, here reevaluates Wrightson’s use of Aboriginal stories.

Mermaids. Faeries. Goblins. Dragons. As a young reader these and similar spirits populated my bookshelves and my imaginings.

I particularly loved stories of ordinary children who encountered these creatures. Thrilled to that cross-over between the everyday and the otherworld.

And yet.

Those ordinary children always lived Somewhere Else.

In the books I was reading, as I grew up in the 1980s, Somewhere Else was usually in the UK. Because it was taken as given – I certainly took it as given – that’s also where the mermaids, faeries, and goblins lived. Although dragons, to be fair, usually lived in Tolkienesque worlds of their own: northern hemisphere fantasy worlds populated by northern hemisphere norms. Where to travel northwards was inevitably to move towards the cold; southerners were always untrustworthy (and often ‘swarthy’); and where strange and fearsome menageries never included dingoes or crocodiles. A white hare could be imbued with mystery and glamour; a white kangaroo was never mentioned.

As a result, I never bothered looking for faeries at the bottom of my garden in suburban Melbourne. I didn’t tap on the back wall of my wardrobe, hoping to pass through. Even the Australian bush held no mystery for me and, to the extent I thought about it at all, it was simply the place where the trees and ferns were.

As a result, I never bothered looking for faeries at the bottom of my garden in suburban Melbourne. I didn’t tap on the back wall of my wardrobe, hoping to pass through. Even the Australian bush held no mystery for me and, to the extent I thought about it at all, it was simply the place where the trees and ferns were.

If magic existed – and as a child I fervently hoped it did – it existed Somewhere Else and, by definition, for someone else. Magic wasn’t something an Australian child was ever going to experience.

Patricia Wrightson changed all that for me.

In her lifetime Wrightson published 27 books, which were translated into 16 languages.[1] She was internationally renowned and in 1986, for her services to children’s literature, Wrightson was awarded the Hans Christian Andersen Medal – the highest international recognition given to authors and illustrators of children’s books.

Among many other prizes, she was also a multiple winner of the Australian Children’s Book Council Book of the Year Award for The Crooked Snake (1956), The Nargun and the Stars (1974), The Ice Is Coming (1978) and A Little Fear (1984). Today, the annual NSW Premier’s Literary Awards include the ‘Patricia Wrightson Prize for Children’s Literature’, established in 1999. The prize of $30,000 is offered for a work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry written for children up to secondary school level.

In Wrightson’s novels, ordinary Australian children encountered magical Australian spirit creatures: specifically, Aboriginal spirit creatures.[2] Wrightson introduced her readers to the fearsome rock creature Nargun, green-eyed Ninya ice men, Yauruk spirit birds, the gentle and courageous Mimi, trickster Potkoorok. Her books are populated with “the creatures born of the land itself, sly and secret creatures, earth spirits.”[3]

In the The Nargun and the Stars a (white) boy from Sydney, suddenly orphaned, is forced to live with relatives on their farm in southern New South Wales. There he encounters the Aboriginal spirits of that place, and adventures ensue. In An Older Kind of Magic (1972), a group of (white) siblings who live in inner-Sydney meet spirit-creatures in the harbourside Botanical Gardens. The standard tropes of childhood magical adventure, it seems, but completely subverted by the Australian settings and the use of Aboriginal magic. For the 1970s, her work was revelatory.

In the The Nargun and the Stars a (white) boy from Sydney, suddenly orphaned, is forced to live with relatives on their farm in southern New South Wales. There he encounters the Aboriginal spirits of that place, and adventures ensue. In An Older Kind of Magic (1972), a group of (white) siblings who live in inner-Sydney meet spirit-creatures in the harbourside Botanical Gardens. The standard tropes of childhood magical adventure, it seems, but completely subverted by the Australian settings and the use of Aboriginal magic. For the 1970s, her work was revelatory.

Wrightson then went a step further: creating a trilogy she would eventually call The Song of Wirrun,[4] where the main character Wirrun, an Aboriginal boy from Sydney, must confront the forces of evil. “Here, in a country young only to its latest settlers but in truth ancient, close to the world’s beginnings, the spirits of the Dreamtime are locked in battle …”[5]

Drawing on Aboriginal stories and culture, Wrightson’s spirit characters held all the power and mystery of 60,000 years of Dreaming – power distinctly lacking in invented colonial fantasies like May Gibb’s saccharine Snugglepot and Cuddlepie.[6]

A gifted and evocative writer, Wrightson opened my eyes (and my mind) to the possibility of magic and mystery that belonged to this place, this continent. She genuinely changed the way I, a white Australian girl from the suburbs, looked at my world. I’ve since spoken with other readers of my vintage, who felt the same.

And yet.

Wrightson’s novels are no longer in print.

Which is probably for the best.

Wrightson was a white woman from New South Wales who, without seeking permission, cherry-picked her spirit-characters from stories belonging to a variety of Aboriginal groups. That she did so in good faith, with benign intentions, and even with positive outcomes, does not ameliorate the fact of her trespass.

Wrightson was a white woman from New South Wales who, without seeking permission, cherry-picked her spirit-characters from stories belonging to a variety of Aboriginal groups. That she did so in good faith, with benign intentions, and even with positive outcomes, does not ameliorate the fact of her trespass.

“The borrowing of one culture’s traditions by another is a serious and risky business,” writes American writer and professor Brian Attebery, in a piece about Wrightson. [7] Risky to the writer perhaps, but potentially far more damaging than ‘risky’ to those from whom the traditions were ‘borrowed’.

Mark Macleod, Patricia Wrightson’s friend and publisher at Random House has explained how Wrightson acted as “an enabler, whose passionate commitment to making stories with an Indigenous theme part of the literary mainstream helped prepare readers for the many Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists who followed. The cross-cultural partnership of Dick Roughsey and Percy Trezise, who changed Australian picture books in the 1970s, for example, found an audience already used to thinking of Indigenous subject matter for children as exciting, dramatic and edgy. That is at least partly due to the high-profile success of Wrightson as a ‘real author’ in the education market before them.”[8]

Other commentators are far less sanguine about Wrightson’s acts of appropriation. Attebery notes that “white societies [display] the impulse to acquire whatever is of value in Indigenous culture while consigning the bearers of that culture to invisibility or extinction.”[9]

Emeritus Professor Claire Bradford, in Reading Race: Aboriginality in Australian Children’s Literature (2001), discusses the tendency of white writers to represent Aboriginal people as an undifferentiated ‘Other’ to the white Australian readership. Bradford questions the image of Wrightson as an advocate or defender of Aboriginality. She writes: “To look closely at … these texts is to recognise how the warm glow of Aboriginality conceals its appropriating and controlling strategies.”[10]

Brian Attebery and Mark Macleod both emphasise that Wrightson was careful to use figures from Aboriginal superstition and myth rather than sacred religious beliefs such as creation myths.

This was an attempt to show respect by populating her fantasies with the creatures of folk tale rather than figures of religious significance, but Clare Bradford questions the legitimacy of such a sliding scale, where all supernatural tales are assigned a value – sacred or trivial – according to the white writer’s judgment: “Cinderella and ‘How The Kangaroo Got Its Hop’ jostling in the lowest level, Adam and Eve at the top with the Rainbow Serpent … Wrightson’s use of the term ‘superstitious’ degrades the narratives that she claims for her own purposes.”[11]

Attebery and Macleod both attempt to frame Wrightson’s work as a positive bridge between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures. Mark Macleod writes, “The reality is that there are Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians and they need to find ways to coexist. Their histories and mythologies are different; their values often seem diametrically opposed. [Wrightson’s] project to try and create a pan-Australian imagery therefore rests finally on the idea that all they really have in common is the land.”[12]

Attebery, however, digs his own grave: “No amount of care can make [Wrightson] into a tribal elder, nor can her use of Aboriginal folklore ever be fully ‘authentic’. However, she can become… a participant in the reshaping of tradition for a modern world in which authenticity is an inaccessible ideal.”[13] To trivialise Aboriginal cultural and spirit stories as mere folklore, and to claim that authenticity is an inaccessible ideal is both patronising and an act of erasure. And, given the brutal history and ongoing racial impacts of the Australian colonial project, it is not for white writers – no matter how well-intentioned – to draw on Aboriginal stories in order to determine and create any kind of ‘pan-Australian imagery’. Bundjalung descendant and poet Evelyn Araluen calls it a trope; calls it “misappropriated cryptomythology”.[14]

Attebery, however, digs his own grave: “No amount of care can make [Wrightson] into a tribal elder, nor can her use of Aboriginal folklore ever be fully ‘authentic’. However, she can become… a participant in the reshaping of tradition for a modern world in which authenticity is an inaccessible ideal.”[13] To trivialise Aboriginal cultural and spirit stories as mere folklore, and to claim that authenticity is an inaccessible ideal is both patronising and an act of erasure. And, given the brutal history and ongoing racial impacts of the Australian colonial project, it is not for white writers – no matter how well-intentioned – to draw on Aboriginal stories in order to determine and create any kind of ‘pan-Australian imagery’. Bundjalung descendant and poet Evelyn Araluen calls it a trope; calls it “misappropriated cryptomythology”.[14]

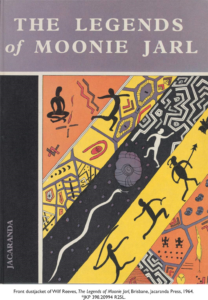

The first Aboriginal children’s book written by Aboriginal people was The Legends of Moonie Jarl, published in 1964. Wrightson’s first novel was published in 1955, her last in 1997. Wrightson was – arguably – displacing would-be Aboriginal writers, rather than paving the way for them.

Yet despite the barriers, Australian Indigenous voices, and their Indigenous stories, have been gaining a foothold in the Australian publishing landscape. The work is far from over but there is now a range of excellent First Nations titles for children to choose from – genuinely authentic stories exploring many aspects of First Nations people’s culture and life experience.

Quite rightly, that’s also where today’s non-Indigenous Australian children can discover the mystery and power of the Country on which they live.

Despite how wonderful I found Wrightson’s books when I was a child, why on earth would I today give a child a book to read about Indigenous Australia that was written (without permission, without authority) by a non-Indigenous writer?[15]

Wrightson’s pastiche stories are no longer required – if indeed they ever were.

Some will no doubt raise some spurious arguments about ‘freedom of speech’, or the obligation to ensure that a fiction writer’s imagination should know no limits, or that Wrightson’s works have to be viewed within their historical context.

And yet.

When so much has been stolen, how can anyone possibly argue that the theft should continue?

In preparing this post, I drew heavily on some insightful bloggers who had covered this ground before me. To explore the issues surrounding Wrightson’s work in further depth I can commend to you:

- Matt Finch at Mechanical Dolphin

- Katherine Langrish at Seven Miles of Steel Thistles

[1] For details, Wikipedia provides a good starting point: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_Wrightson

[2] I’m deliberately not using the standard ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’ catch-all phrase here, because as far as I know Wrightson only drew on Aboriginal cultural stories, not those of Torres Strait Islanders.

[3] Taken from the cover blurb of The Ice is Coming, Hutchinson, 1977.

[4] The trilogy comprises The Ice is Coming (1977), The Dark Bright Water (1978) and Behind the Wind (1981).

[5] Again, taken from the cover blurb of The Ice is Coming, Hutchinson, 1977.

[6] See also ‘Mrs Kookaburra Addresses the Natives’, Drop Bear, Evelyn Araluen, UQP, 2021.

[7] Attebery, Brian. “Patricia Wrightson and Aboriginal myth.” Extrapolation, vol. 46, no. 3, fall 2005, pp. 327+.

[8] https://mechanicaldolphin.com/2010/10/27/patricia-wrightson-part-1-the-song-of-wirrun-and-beyond/

[9] Attebery, Brian. “Patricia Wrightson and Aboriginal myth.” Extrapolation, vol. 46, no. 3, fall 2005, pp. 327+

[10] https://mechanicaldolphin.com/2010/11/01/patricia-wrightson-part-2-the-representation-of-aboriginality/

[11] https://mechanicaldolphin.com/2010/11/01/patricia-wrightson-part-2-the-representation-of-aboriginality/

[12] https://mechanicaldolphin.com/2010/11/05/patricia-wrightson-part-3-outsiders-and-indigenization/

[13] https://mechanicaldolphin.com/2010/11/01/patricia-wrightson-part-2-the-representation-of-aboriginality/

[14] ‘The Trope Speaks’, Drop Bear, Evelyn Araluen, UQP, 2021.

[15] And I say that as a non-Indigenous writer who has written a book with, and about, an Indigenous man (a book written with his permission, with his authority, and with his trust).

Book covers used to illustrate this article:

Patricia Wrightson, The Crooked Snake, 1955

Patricia Wrightson, The Nargun and the Stars, 1973

Patricia Wrightson, The Song of Wirrun, 1987

Wilf Reeves, The Legend of Moonie Jarl, Jacaranda, 1964. Illustrated by Olga Miller

.

Michelle Scott Tucker is the author of Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World (2018). And she is co-writer with Aaron Fa’Aoso of his upcoming memoir So Far, So Good, due out Sept 2022.

Thanks for this thoughtful post. I have to agree with you about everything you’ve said. Like you I devoured Wrightson’s works in my childhood and, also like you, found my perspective of this land of my birth changed by them. The beauty of her writing and likely good intentions do not, however, outweigh the act of appropriation. I still think fondly of those books but it is right that they are seen by a different standard today.

Thanks Denise, it’s always lovely to hear from a fellow traveller. Like you, I think it is possible to recognise the way those books made me feel back then while still firmly acknowledging that ignorance is not an excuse. At the risk of sounding like Oprah (!) as soon as we know better, we need to start doing better.

HI Michelle,

I agree with all you say. I have (of course) to say that it has been historically a common process for books to be written about, then with, then by Aboriginal Australians.

And the colonial structures and processes continue.

Katie Langloh Parker’s rendition of Aboriginal stories from the Euahlayi are still a useful resource, although now Julie Janson (Darug woman) is writing of a very nearby Country but draws upon orature and, I think, Katie’s work in her own writing.

Repatriation of the written word is not possible, so all we can do nowadays is be aware that appropriation has occurred, and place it in its historical context.

Arthur Upfield’s Bony stories have the same issue, and are more location-specific than Wrightson’s work, and I hear people still hunt out those locations, crime fiction as travel literature, and contemporary authors like Chris Hammer still have credible Aboriginal Australian characters, like Bessie Walker in “The Seven”. So the game remains afoot and evolving.

I was given The Crooked Snake in 1958, and it is still somewhere on my family’s shelves. I will have to re-read it and discuss it with Ms 10.

Ms 10 and her siblings attend a Steiner school which teaches some form of pantheism. I wonder now to what extent Aboriginal myths and legends are included, and indeed appropriated.

A very thought provoking essay, thank you Michelle, and one with which I agree entirely, especially your final line.

Thanks Bill, I enjoyed writing this one – I’m glad you asked me for it! I think we all need to be on the look out for appropriation, even (or especially) the so-called benign variety. And white people need to call it out, instead of relying on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to always carry the burden of doing so.

That was excellent, Michelle. I too absolutely loved the Patricia Wrightson books but would not feel particularly comfortable recommending them today, if they were even available. That they are not available says a lot about a heightened awareness of appropriation.

Thank you Janine. ‘I Own The Racecourse’ was published as a Text Classic in 2013 but yes, the others seem to have been a long time out of print. With so many excellent First Nations writers to choose from, it would be a retrograde step to publish Wrightson again, I think.

Excellent post Michelle, thanks so much for writing this. I have to say that I find it hard to criticise artists/creators working in a different time whose intentions (probably) were good, but in the end, it’s not really for me to say. What I do say or agree with, though, is that those artists/creators’ works having been superseded, as they should have been, do not need to be available now.

BTW I was aware of Patricia Wrightson back in the mid-1970s, through my library studies, but that was after my childhood! I probably would have only been interested in books like I own the racecourse, which I remember reading for library school, and not her Aboriginal inspired tales – not out of any awareness back then of appropriation issues (because we weren’t aware back then) but because I never was, as a child, much interested in fairies, magic, or spirit beings. I mean I thought fairies like Tinkerbell (haha!) were cute, but I never gave them much serious thought. My interest was always tended to realism.

Thanks Sue, and I absolutely agree that examining the past is never as straightforward as we might wish. Interesting too, that ‘I Own the Racecourse’ doesn’t include Aboriginal spirits but the main character has a learning disability – more ‘own voice’ complications…

I love how different readers are drawn to different things – I’m still drawn to stories about magic and spirits, quite frankly! Some of Wrightson’s work, though, might be better described as magic realism. I’m thinking particularly of ‘A Little Fear’, about an older woman trying to avoid living in a retirement home. Something strange seems to be stealing eggs from her chook pen – an ancient spirit? Or the onset of dementia? I think I know which I’d prefer, lol.

Ha ha, Michelle, put that way, I might prefer the ancient spirit too!

A new author to me, although I see some similarities between her work and the work of Christie Harris, from the western coast of (the country currently called) Canada. She, too, was steeped in coastal Indigenous storytelling and her work was, as you’ve described it, a bridge for me to travel to different ways of thinking and being in the world, when I was a child.

I recognise the validity of all the opinions you’ve cited here and appreciate how clearly you’ve expressed the complex issues. One thought I would add is that the question of permission and consent is also complicated by the fact that not all members of an Indigenous group necessarily agree on what/how stories are to be told, so, for instance, where one member might believe a story extends a hand in the work of reconciliation with settlers, another member of the same group might believe that story should be protected and remain with the community. Gaining the permission of some members still engages in what other members might consider appropriative/harmful behaviour.

How interesting that coloniser literature in Canada and Australia followed similar paths – thank you for the heads up and your thoughtful comments. And yes, gaining permission and consent is indeed endlessly complicated – often made more so by the fact that in some cases selected cultural stories are only known because they were recorded back in the day by a coloniser… As a white writer working with a Torres Strait Islander, I’m learning (often the hard way!) to simply sit with those sort of complications. Some challenges aren’t mine to resolve.

Really great post, Michelle. I reread the Nargun and the Stars (a childhood favourite of mine) back in 2015 when I first started my book blog (https://tintededges.com/2015/03/02/the-nargun-and-the-stars/). As an adult, I was able to clearly recognise that key elements of the story had been appropriated from the Gunai/Kurnai nation and recast in a New South Wales setting, but still felt that the story had ongoing value. However, 7 years on and with the benefit of blogs posts like this, I am not sure I can even say that any more. It is a beautifully-written story but regardless of Wrightson’s intentions, we do have to ask: can we continue to condone the theft of culture in literature, when Aboriginal authors are still in many ways excluded from mainstream publication?

Thank you Angharad, and your own post about The Nargun and the Stars is great too. It’s interesting, though, how our views change over time – as they should, I suppose, as we approach the world with more and better information. I agree that Wrightson’s failure to even acknowledge the First Nations communities from whom the stories were taken is a huge and terrible ommission.

I suspect similar works could – should – only be published today if they were, at the very least, co-written by Wrightson and a First Nations author. But given the calibre of First Nations writers who are publishing in their own right (Nardi Simpson, for example, beautifully depicts the intersection of the ‘real’ world with the Indigenous otherworld) perhaps white writers need to just step away from First Nations’ stories. Robbie Arnott, for example, has successfully created his own unique mythological spirits and creatures, set in an Australian landscape (Flames, Text Publishing, 2018). So it is possible.

Fascinating, thank you. I didn’t come across her books as a child; I don’t think I encountered many books set in Australia or by Australian writers, apart from the Silver Brumby books (I hope they’re still OK?) and Alan Marshall’s “I Can Jump Puddles” – hm, see the horse connection. A great article still even coming to it from a position of no knowledge at all.

Thank you Liz, and unfortunately Australian writers are very used to their work not being widely distributed internationally (or, indeed, at all). You are clearly a reader after my own heart though, because I loved all the horse books too! And yes, I do suspect that the Silver Brumby books have stood the test of time and are still ok. Phew!

Aha, marvellous, always good to find another horse book fan (please don’t read the final Black Stallion book if you haven’t already been horrified by it, though!). And that’s good news about the Silver Brumby books! Still hard to get Australian books here – I have a few TBR that either Bill has sent me or I’ve managed to get through Book Depository. Your new co-authored one looks like it will be available in Kindle here so I’ve added it to my wish list.

I have a warm spot for some of Wrightson’s books because they were illustrated by Margaret Horder, who is my first cousin, once removed. Not that I recall ever meeting her.

The Crooked Snake, which my own first cousin gave me in 1958, is the only Wrightson I am aware of, or was till I had to pull up book covers for this post. I would like a famous person in my family I could point to, but nada, not even an almost-made-it footballer. Michelle didn’t discuss the illustrations, I don’t think, I wonder if they are appropriation too.

I could not disagree more. This is an extremely ungenerous reading of a sizeable literary legacy, coming to an awfully censorious conclusion. It is unlikely, and probably impossible, that in *any* of Wrightson’s books you would find her not grappling, in some form, with the questions of ownership of story and myth and legend; the fact is that she is very sensitive to these issues. To dismiss her attempted solution – ranking legends from ‘sacred’ to ‘superstitious’ – as useless is of a piece with that common progressive flaw, the dismissal of the good because it is not the perfect, and answerable to the same criticism: how, then, is any progress to be made if all attempted progress is found to be imperfect and therefore useless? The idea that she viewed and portrayed Aboriginal people as monolithic, even more, that she did so (whether consciously or unconsciously) as part of the colonial project of Indigenous erasure is likewise false; she takes care with all her characters; Barney (the white kid) and Eustace (the Aboriginal kid) in ‘The Rocks of Honey’ are both portrayed with equal sympathy and compassion and individuality, to take just one example. Worst of all about this rejection of Wrightson is a rejection of something we ought to be working towards as a nation today – reconciliation; all of Wrightson’s plots that come to mind centre around a reconciliation between different forces, different spirits, the old and the new, the land and the people. Few people would now suggest that stories can be freely appropriated as they used to be, but to imply (as seems to be the case here) that any such use of these stories by non-Aboriginal people is committing the crime of ‘appropriation’ is utterly naive about the process of storytelling and the nature of folk customs and tales of the fantastic. Wrightson’s books are and remain splendid and sensitive examples of storytelling and I would *absolutely* give them to my child to read.

TimT, I’m glad you took the time to express your opinion. We often argue in these and other pages about writers being progressive ‘for their time’. I don’t doubt Wrightson’s good intentions but whether she realised it or not (and I imagine not) her mindset was still colonial. Michelle can speak for herself, but the quote that jumped out at me was “To look closely at … these texts is to recognise how the warm glow of Aboriginality conceals its appropriating and controlling strategies.” (Bradford).

wadholloway, thanks for your response. Your comment that Wrightson’s ‘mindset was still colonial’ seems to be more an observation than effective criticism, since any inheritor of colonial Australia’s legacy could by the same definition be ‘colonial’, and there is no clear historical point at which people could not be said to be ‘colonial’ anymore. Save the unprecedented and improbable historical event of every single piece of Australian land being returned to the Indigenous people, the facts of colonisation are not going to be changed.

I would say that Wrightson’s writing represents a cultural response to a certain cultural problem (or set of cultural problems): how, as a colonist (or immigrant, or ‘new Australian’, or Anglo Australian – pick your label) to write as a fabulist about a new land without using the language and characters of English fantasy based in the English/British countryside? Her solution is labelled today as ‘appropriation’, but the label is misleading and Wrightson’s writing is a good deal more subtle and sensitive to cultural and personal conflicts of her time than that. Her books leave a valuable literary legacy and it would be a huge disservice to not only her but to Australian literature to bar them completely from the literary record. Finally, the literary problems she responded to have not gone away, and, unless fabulism completely disappears as a literary genre, all ‘colonial Australians’ with an interest in literature will need to grapple with the problems Wrightson grappled with.

Incidentally, I see that this is not exactly what has happened (in spite of suggestions to the contrary in the article): after I started googling ‘The Nargun and the Stars’ – which I’m re-reading now – I happened upon several websites (including this one(!)), which indicated that not only was it made into a television serial around the time of publication, but was made into a ballet much more recently (2009).

I think to dismiss all the spirit Wrightson books as mistaken is to oversimplify a very knotty problem. How does a white person write fabulist narratives in Australia without committing appropriation? Due to the regrettable fact of colonialism this is now home for us. Fairies and other nature spirits feel, as you said in the beginning of your essay, as foreign to me as the landscape they come from.