In this short story, a wealthy young man meets, on a steamship trip from South Africa to Melbourne, a not so well-heeled young woman and her mother, who is ambitious for a good marriage for her daughter.

He came in early that night after a lonely dinner, and half an hour at a musical comedy which for some reason had vaguely annoyed him. As he slammed the door he was irritably conscious of the almost solemn hush that pervaded the great hotel. After the cold air of the night the room felt drowsily warm. His feet sank into the soft pile of the carpet; his bed was neatly turned down, and a luxurious armchair awaited him. On the dressing table were his silver-backed brushes and combs and a box of cigarettes with his monogram engraved on them. He looked round and a sardonic smile crossed his keen, dark face. It had taken him 10 years to achieve this luxury, and now that it was at his command he realised that he had been happier in his camp on the South African gold fields dreaming of the time when his for tune would be made. His return to Melbourne had been something in the nature of an anticlimax. Those who would have benefited by his money were dead, while other people seemed chiefly interested in what they could get out of him. He had learnt, or thought he had learnt, quite a lot about human nature in South Africa.

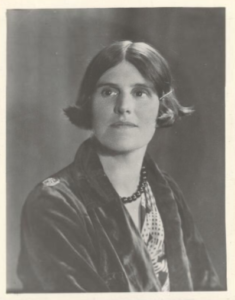

Of course the trouble was that he missed Paula. It was amazing how he did miss her. At the confusion at the end she had given him no opportunity of saying what he felt. Her attitude had been that they were steamer friends only, and that a pleasant little episode was now ended. How she had enlivened the dull journey from Cape Town to Melbourne! With her vivid colouring she had bloomed like an exotic flower among the rather nondescript crowd on board. At first he bad admired her from a distance, alarmed at the obvious manoeuvres of her match-making mother to throw them together. He had no intention of being rushed into matrimony, and, though he was without personal vanity, he was quite well aware that to many women his money made him a prize worth having. It was Paula herself who had cleared the air and defined the position between them.

“You know,” she said, looking at him with laughing eyes, “there’s three weeks’ solid boredom before us, and we could be quite good friends only you are afraid mother is determined you should many me. Well, you needn’t be alarmed. Even if you wished it I wouldn’t marry you. There’s someone else. This trip is in the nature of a cure, but it hasn’t acted. I’m more in love than ever. He’s dreadfully hard up, poor darling. but I don’t care, even if we do have to live in a couple of rooms and scrape along on five pounds a week. So that’s that! Now we can be friends quite comfortably, can’t we?”

Her candour had amused him, and he found her the most charming companion he had ever known. If sometimes her tact failed and she plied him with descriptions and reminiscences of Reggie – that was the fellow’s objectionable name, he discovered — he grudgingly admitted that some allowance must be made for a woman in love.

Reggie did not come down to meet the boat — he was not one of the idle rich, she gaily informed him, but hid to work hard in order to furnish their little nest — and he watched her drive off with an uncomfortable feeling at his heart. Was it possible that he felt jealous of Reggie?

The clock on the mantlepiece chimed the hour, and he stared at it dismally. Only 9 o’clock! What on earth was he to do? Impossible to go to bed, and no use going downstairs; there was no one in the hotel who stirred him to the remotest degree of interest. What was Paula doing? With Reggie, he supposed. At the thought he felt the same pang he had experienced before. Paula to marry a poor man! The idea was absurd. Only wealth could give her beauty the setting it required. What a fool he had been to acquiesce in the friendship she had given him. Why hadn’t he made love to her while he had the chance? The setting had been ideal. Moonlit nights, and days of blue and gold. Long, long hours they had spent together, while she had talked of Reggie and he had listened to her. What a fool he had been!

As though his questionings had called her out of the silence, the telephone on his table shrilled loudly, and he heard her voice at the other end of the wire.

“We’re here, John,” she said, “on your trail still, you see.” Did he imagine it, or was there a faint tinge of bitterness in her voice. “John Ramsay is quite an important person in his own home town. We saw your name in the list of guests, and established ourselves here at once. I thought I had better break the news to you so that you could escape if you wish. I rang up before, but you were out.”

“Paula . . . escape! But you’re joking, of course. It was strange how his hand was trembling. “Where are you now?”

“In the lounge if you want to see us.”

He heard the receiver click as she hung up.

She was sitting with her back turned to him as he entered the lounge, almost lost in the depths of a great arm chair. He could see the outline of her sleek, dark head resting against the orange cushion. For the first time he felt grateful to Mrs. Wainwright. It was her tactics that had brought them together again. Now that fate had given him another chance he was going to take it.

Mrs. Wainwright was the first to see him, and waved a carefully manicured hand in his direction.

“Why, Mr. Ramsay!” she exclaimed, as he threaded his way through the chairs to her side. “This is a surprise.”

Paula flung down the paper she was reading and smiled up at him. He thought she was looking a little pale, and there were shadows beneath her eyes. Worrying about the objectionable Reggie, he thought savagely.

“Yes, isn’t it a surprise,” she said wickedly. “We had no idea you were staying here.”

“It’s luck for me, anyway,” he returned, beckoning a passing waiter and ordering coffee. “I was feeling so bored that I was just contemplating going to bed when I discovered you were here.”

Mrs. Wainwright stifled a yawn behind an elegant hand, then gathering her paper together, rose. “It’s just like old times, isn’t it?” she smiled. “If you will excuse me I will leave you two together and go to bed myself. I haven’t recovered from the voyage yet… Don’t be late, dear,” and she sailed off.

When she had gone silence fell between the two of them. There were a hundred questions he wanted to ask her, but for some reason he felt tongue tied. The happy ease of their relation had been disturbed. He stared at her hungrily, wishing she would look at him, but she avoided his eyes. She, too, seemed self-conscious and uneasy as though she realised that things could no longer remain as they had been.

“I suppose it amuses you,” she said at last. “But I hate it. I do wish mother wouldn’t be so obvious.”

“She knows we’re friends,” retorted Ramsay. “Why shouldn’t she leave us alone?”

“Because —” She leant forward, her hands, loosely clapped together on her knee, “it makes me feel cheap. We’re not on the boat now and things are different.”

“Of course,” he interrupted harshly, “I had forgotten. There’s Reggie to be considered now, and he mightn’t like it.”

“Yes — there’s Reggie.”

The waiter brought the tray, with the coffee, and he sat in gloomy silence while she poured out a cup and passed it to him. “I’ve always made a joke of it,” she went on, “but it hurts sometimes — not on my account so much, but on hers. I would hate you to misjudge her, but I feel you do. It’s for my sake she does it. She has always been haunted by the fear that when she is gone I will be left with nothing. You see, she has only an annuity, and I suppose we both have rather extravagant tastes, for we live up to every penny of it. Quite frankly, from my childhood I have been brought up with the idea that I must make a good match. Of course I could go to work as other girls do, but I’ve never learnt anything useful. What could I do? Nursery governess perhaps, or companion to an invalid old lady with a pug dog. That’s about the limit of my qualifications. In the meantime —.” She looked up at him and laughed, “I sit and drink coffee in the lounge of an hotel and bore you to death with my woes.”

“You’ve changed,” he said suddenly. “On board you never talked like this.”

“Changed?” Her lips twisted in a wry little smile. “Well, perhaps I have. On board ship one simply doesn’t think. It’s like another world altogether. But home again —” She shrugged her shoulders. “One must face facts. It is rather galling to realise that you are an absolutely useless person.”

He was puzzled by her manner, and wondered what had occurred to distress her. Was it possible that Reggie had failed her?

“You’re forgetting Reggie, aren’t you?” he said, a jealous note in his voice. “Surely he doesn’t think you useless?”

“Reggie? We do seem to come back to him, don’t we? He has made me realise what a useless creature I am. Poor darling. I’m sure to make a fearful mess of darning his socks.”

He felt inclined to curse both Reggie and his socks, and looked so glum that she laughed outright.

“Now I’ve finished my monologue, so tell me about yourself. The papers have rather spread themselves about you, haven’t they? I had no idea you were such a celebrity. From paper boy to mine owner! Tell me, is it true? Were you ever a paper boy? It quite upset mother for a time. She thought it tactless to mention the paper-boy part of the business, though the mineowner rather gilded the pill. Why don’t you smile, John? I’m doing my best to be bright. On board you always found me amusing.”

“As you reminded me yourself,” he said curtly, “on the boat things were different.”

“Why,” she murmured, “you do sound cross. This is certainly not one of my successful nights.”

“Paula,” he said abruptly, “let’s have done with this nonsense. On board ship I was a fool, but you disarmed me with your talk of friendship. I just let myself drift, and never thought – never realised. Now things are different, Paula!” He leant forward, forcing her reluctant eyes to meet his. “I love you — isn’t there a chance for me?”

The colour flooded her cheeks and her lips quivered, “Oh,” she whispered, “why did you say it? Now you’ve spoilt everything.”

“You mean there is no hope for me? You are really going to marry this fellow?”

She bent her head for answer.

He sat quite still, trying to realise that he had failed. Until that moment he had not known how much he had hoped. He fancied that a man across the room stared at him curiously, and wondered if his defeat was written so plainly oil his face, or perhaps it was only that the other recognised him. His photograph had been in the paper that evening. From paper boy to mineowner! The ironical humour of it struck him, and he laughed suddenly.

“Don’t!” exclaimed Paula, shrinking in voluntarily from the sound. “Don’t laugh like that — it hurts.”

“I can be amusing, too,” he said bitterly. “It’s quite a good joke if you have the right sense of humour. You asked me just now if I had ever been a paper boy. Well, I was! I used to hang around the door of this hotel with my bundle of papers, watching the people go in and out. I used to picture my mother living here in luxury instead of working her fingers to the bone to keep me in food and clothes. I swore I would be rich for her. She died just as my luck was about to turn. After that things lost their savour a bit, but I was interested in the game for its own sake and keen enough. Then — you came. My money has failed me there. You’re poor, or comparatively so. You told me quite frankly that you had been brought up with the idea of making a good match, and yet, in spite of that, you’d sooner marry a man making £5 a week than have me with all my money thrown in. I’m not whining. I respect you for it. I had an idea once that money would buy anything. Now I know it won’t give you what you really want. Well!” He rose as he spoke. “Good luck, Paula, and thanks for everything. Even if I find it impossible to carry on the farce of friendship, I’m grateful. Send me —.” He hesitated before uttering the hateful name. “Send me Reggie’s address. I can put him on to something worthwhile. You’ll let me do that at least?”

She did not answer. He stood looking down at her, wondering what she was thinking. Perhaps she was wishing he would go. He flushed at the thought. An awkward moment for both of them best to get it over.

“Good-bye, Paula,” he said, hoarsely, “and don’t worry about your mother. I will fix things with her.”

The warm air of the hotel felt stifling as he turned away. He must get out somewhere — walk till he was too tired to feel anything but fatigue. He took his coat and hat and was about to swing open the big doors at the entrance, when the hall porter slopped him.

”Mr. Ramsay, sir? Miss Wainwright told me to tell you she would like to see you in the lounge.”

He hesitated. Surely everything had been said between them. Still, it was hardly a message he could disregard.

“Thank you,” he said, curtly. “Just take these things, will you.”

He felt more at ease when he saw that, save for Paula, the lounge was deserted. If they had to have another parting he preferred it should be without onlookers. Or, perhaps, it was merely that she wished to give him Reggie’s address? Yes, that must be it.

“I’m here,” he said coldly and superfluously.

“So I see,” she answered in a meek voice.

This meekness was so unlike Paula that he stared at her in astonishment. She looked nervous, rather like a small child expecting punishment, but he hardened his heart against her. Her haste to take advantage of his offer to help Reggie struck him as unseemly. Did she think he was likely to change his mind in the morning?

He waited. Still she did not speak. Then he glanced at his watch. “If it’s about that address?” he suggested.

“That’s just it.” She twisted her hands together nervously. “John, I’ve lied and deceived you. I meant to let you go without telling you the truth, but I can’t. There isn’t any Reggie.”

“What!” he almost shouted. Then realising where he was, lowered his voice. “Paula, you must be mad, or am I? Why, you’ve described him to me a dozen times. I believe I’d recognise the fellow in the street if I saw him. Blue eyes, fair hair, features like a Greek god, and the manners of a Sir Walter Raleigh. Paula, there must be a Reggie!”

She shook her head speechlessly.

“But why?” He passed a wondering hand across his brow. “Tell me why Reggie was necessary?”

“You made it necessary,” she answered, half tearful, half angry. “When I met you on the boat I knew what you were thinking and hated you for it. Oh, I didn’t blame you-mother was trying to throw us together — but I hated you all the same for daring to know it. That’s why I had to have Reggie. I knew if you thought I loved another man I would be safe. Even if mother was too obvious you would know I didn’t want to marry you, and we could treat it as a joke. It was the only possible way to save my self-respect. And you were cynical — so hateful. You believed-oh, yes, you did-that you had only to drop the handkerchief and any woman would fall into your arms. Your hateful money! I wish you were a man getting five pounds a week. You might have a little faith in human nature then.”

She paused breathless.

“Heavens!” He checked a wild impulse to laugh. “Drop the handkerchief-any woman fall into my arms. Did I really give that impression? What an unutterable ass I must have seemed. You’ll have to teach me better manners when we’re married, Paula.”

“Married?” She opened her eyes wide in apparent surprise. “I’m not going to marry you. What has given you that idea?”

“I thought it would be a nice surprise for your mother,” he said cheerfully. “Ah, Paula,” he added softly, “don’t let

us waste any more time. You’ll forgive me, won’t you?”

“Excuse me!” He heard a discreet cough at his elbow and turned swiftly. It was the hall porter.

“Miss Wainwright is wanted on the telephone,” he announced. His eyes, as they met Ramsay’s were blank of any expression.

Ramsay thrust his hand into his pocket. A crisp note changed hands. “Just say that Miss Wainwright is engaged,” he said. “Permanently,” he added, as the porter withdrew.