by Evelyn Blackett (1863-1943)

by Evelyn Blackett (1863-1943)

A young woman forgoes her chance of love for the sake of her family.

An oppressively hot February afternoon, the air above lay still, and the earth seemed as silent and lifeless as if suddenly dispeopled and forgotten. The sea was at rest, and of an intense indigo blue.

The beach was deserted — an unusual occurrence at that time of day, for the residents of Torquay were fond of strolling thereon, and it was the favourite promenade of visitors – whether the elite, or those who were fortunate enough to be able to snatch a brief respite from business and its attendant worries, or come and bring the latter with them. Launceston was always well represented; usually, there was a fair sprinkling from Hobart, and even a few from the other side of the Straits condescended to patronise Torquay. “It was execrably tame,” they declared, “but an excellent sanatorium.” After all, the beach was not completely deserted, for lounging beneath the shadow of some enormous rocks were three ladies. A glance would show that all three belonged to the fashionable world.

Mrs. Gerald Leighton was the wife of a wealthy Sydney station-owner. She was a trifle below medium height – what the French call “petite”; her features were delicate; her hair and eyes dark and soft; her dress, which was palest cream, elegant in its daintiness and simplicity. But, perhaps her greatest charm lay in her voice, which was low and musical. She was very amiable and lovable, though her manners were variable — sometimes brilliantly gay, sometimes pensive almost to sadness.

Stella, Mrs. Leighton’s sister-in-law, was a tall, stately woman of about twenty-four; her dress, a complete sea-side costume — wonderfully and fearfully made — was irreproachable, and added to the queenliness of her appearance. Her disposition was cold and passionless as her eyes, though she was not incapable of warmth or feeling, as when a time came to stir up what was within her proved. Like all deep natures, she was resolute and determined, and would have sacrificed her life — or another’s — rather than turn from a purpose once resolved upon.

Stella was an orphan and an inmate of her brother’s home, but independent, as she was the mistress of a very fair income. Her only brother Gerald, her senior by many years, was her idea of manly excellence. All her affections centred upon him, and, as years passed, her love grew until it became a kind of idolatry. Her affection did not manifest itself by soft words and caresses, but by a sort of dogged fidelity, that would turn upon and fiercely attack anyone who dared speak disparagingly of him. Any neglect or slight exhibited towards herself she treated with cold contempt; but the same towards her brother would cause her dark eyes to flash, her lips to quiver, and sometimes call forth a torrent of angry reproach. His wife she regarded as an interloper, a creature who could not appreciate the value of the inestimable treasure she had won. For her brother’s sake she smothered her feelings of dislike as well as she could, and though the natures of the two women could not harmonise, they seldom really clashed, But woe to the wife if ever a day came when she seemed to all short of wifely duty.

The last — and in all respects, the least of the trio — was Maude Cressington, Mrs. Leighton’s youngest sister. To her, life had been, and she expected it ever to be, nearly all poetry and brightness. No wonder, then, that her great blue eyes were always brimming with fun and merriment, her lips wreathed with smiles. No need to describe such a butterfly as she very minutely. There are thousands like her — gay, girlish, honest young things; perhaps a trifle too thoughtless, but that’s a fault that time and experience will cure — perhaps too quickly. Maude was amiable, candid, pretty, and young, and what more could the most puritanical or fastidious desire?

Oh! and here clambering over the rocks, half leading, half being led by a noble Newfoundland, comes a perfect three-year-old cherub — not with folded wings and glistening raiment — but in a charming little sailor suit; his hands full of marine treasures.

“Oh, look, Aunt Maudie, such booties for your klection!” As he spoke, he tumbled into Mrs. Leighton’s lap, and flung towards Maude, who was reading, a moderate sized reptile in an advanced state of decomposition, and several specimens of the mollusca family, then turned to witness the recipient’s pleasure and appreciation. Maude shrieked, and ejaculated something not particularly lady-like. Young Gerald laughed defiance from his mother’s sheltering arms, and after mischievously remarking, that “Auntie did make awfully ugly faces,” scampered off with Nero for another run on the sands before returning to the hotel.

By this time the earth was re-awaking, and the air becoming cooler; and as the descending sun bathed the clouds with gold, the sea partook of their glory, and for a time dazzled the eyes with a flood of light and glitter, then faded away like the dying hues of the dolphin; then succeeded shades of purple and coral, and lastly, ocean and sky became a twilight tint of grey blue.

Then could be heard the voices of children at play, the patter of footsteps displacing pebbles and shells on the beautiful sandy beach, the murmur of voices, the echo of laughter, and the confused sound of birds, beasts, and insects, all stealing forth to enjoy the purer air of heaven after the heat and burden of the day.

Still, the three beneath the shadow of the rocks stirred not. Mrs. Leighton and Stella appeared occupied with their own thoughts, as they sat listlessly watching a solitary gull pecking in a heap of kelp, and listening to the unceasing music of the waves, and the clanging of the pebbles, caused by the receding tide, whilst Maude was engrossed in her book. Though speaking was no longer an effort, as it had been a few hours before, only a few desultory remarks were exchanged, until Maude’s last chapter was concluded, and the book closed with a sigh. “Really, Stella, you ought to read ‘A Day too Late’; you could then no longer doubt the existence and reality of love!”

A somewhat contemptuous smile hovered for a moment around Stella’s perfectly chiselled lips, as she replied, “I do not doubt its existence; it is the shallowness and incapability of most people that —” Maude interrupted with “I am very glad that at last you are learning to be womanly and reasonable. Here are some daisies, find out if a certain gentleman loves you, or if you are sure on that point, ascertain to what degree!”

As she spoke she flung a couple of Marguerites towards her companion. “Thank you,” Stella replied in her coldest tones, “but I prefer to leave such play to children — and fools,” she added, as an after-thought.

“Well, Gerty,” Maude continued, “you measure someone’s love; you are not too dignified to tear a poor little innocent flower to pieces. Poor Stella is afraid that the oracle will tell her that Mr. Hamilton loves her ‘little’ or even worse!”

Stealthily the tormentor glanced at her victim. What she saw warned her that it would be well to desist, so after muttering “the hot Leighton blood is rising,” proceeded to dissect her daisies, petal by petal.

“Little — much — passionately — unto death — not at all.”

“Maude,” said Mrs. Leighton, “please run to the point and call Gerald, I am afraid it is growing too chilly for him after the excessive heat.” Maude hurried off, and Gerty picked up a daisy and carelessly plucked off its petals. A fourth petal was the last, and she murmured “unto death — loves unto death.” At that moment Stella fixed her eyes scrutinisingly upon her sister-in-law, and with a smile that betokened neither pleasure nor sympathy, significantly remarked, “I should think there was no need for you to seek to prove that your husband loves you, even with a love that will endure until death. God knows he has said it by word and deed often enough!” She would have said more, and perhaps, harsher, but Gerty, her brother’s wife rose, and with an anguished face and trembling voice begged her to spare her reproaches. “Oh Stella, pray don’t! I am striving to do my duty, don’t judge me too harshly.”

Then clenching her hands she exclaimed — “You consider yourself, and I suppose you are, a much better woman than I, then, oh, if you are a Christian pray for me; pray that God will be more merciful to me than some of my fellow-creatures are!”

Some people were advancing towards them, and Stella had only time to reply — “Mind, Gerty Leighton, if you drag my brother’s name down, you’ll suffer for it!”

Gerty had trembled like a leaf in a storm during the outburst, and now sat, shivering and pale, watching the tiny wavelets that were playing beneath her feet, and wishing that a great foam-crested billow would dash in and carry her away — anywhere, to some haven of rest and safety, from remorse, temptation, and love. But suddenly, wafted from a distance by a gentle zephyr, there fell upon her ear and sank into her heart one word, uttered in an exulting baby voice, “Mamma!” It was only little Gerald’s voice repeating the name he had said hundreds of times since his infant lips had learned to frame it, but the sound had a wondrously soothing effect.

Maude and Gerald had almost reached the rocks when Stella asked, in her usual tone of voice, not a trace of her late agitation perceptible: “Gerty, were you thinking of Gerald, of the noble heart that beats only for you and your child, when half-an-hour ago you ruthlessly destroyed a flower? I noticed the emotion you would fain have concealed as you murmured the words ‘unto death!’ Was it his love, the only love that should thrill you, that you measured, and found stretched through years and years, and still was yours when all else was slipping from you?”

“What right have you thus to question me?” Gerty demanded, huskily.

“Tell me truly,” was the only reply.

“Then, no!” was the desperate and defiant answer. “I was thinking of him whose image is before you, whom, despite your manifold theories, you love even as I do!” A moment’s pause, and Gerty added, “At least, as I once did, and many waters cannot quench love.” The last words had been uttered in a low, dull tone, more to herself than her companion, but if they had been shouted in trumpet tones they could not have been more deeply impressive.

With a smouldering fire breaking out, as it were, on her face, and a strange, half savage gleam in her eyes, Stella said, in a low hoarse whisper, “Gerty Leighton, the day is not far distant when you will regret that confession.”

(continue reading here)

~

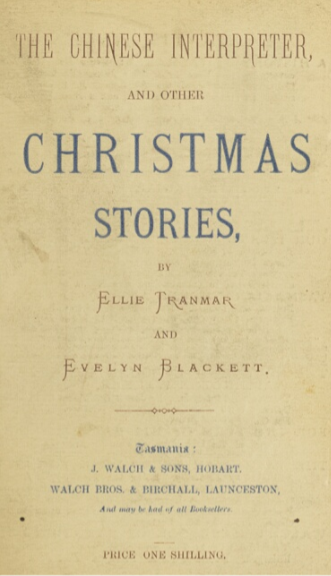

Blackett, Evelyn, “For the Sake of Scalby”, in The Chinese Interpreter and Other Christmas Stories, J. Walch & Sons, Hobart (1881) – link to SLNSW digital collections