by Elizabeth Lhuede

Another in our series of forgotten Australian women writers: Bella Guerin (1858-1923).

Another in our series of forgotten Australian women writers: Bella Guerin (1858-1923).

Back in February, the Trove Facebook page posted the question, “Have you used Trove to research women’s history?” Accompanying the post was a photo of a group of women medical students at the University of Melbourne in 1887. It reminded me that, in my efforts to compile the archives, I’d stumbled over several poems written by the first female graduate of Melbourne University, Bella Guerin.

In honour of International Women’s Day this month, it seems good a time to give Guerin her due.

Bella Guerin was born Julia Margaret Guerin in Williamstown, Victoria, in 1858, to Julia Margaret (nee Thearney/Kearney) and Patrick Guerin. Bella’s parents and older children had arrived in Melbourne from Ireland on the ship, Marco Polo, and her brother, Marco, was born onboard. Patrick Guerin rose through the civil service and became the governor of Ballarat Gaol. Bella was educated at Ballarat College, went on to earn a BA and became the first female graduate of the University of Melbourne, “when ladies were first admitted to enter for the ordinary examinations for degrees”.

After graduation, Bella began a teaching career and, by 1886, was “presiding over the arts’ class at The Loreto Convent” in Ballarat. In 1889 she held “university classes” at the Ballarat School of Mines, and in 1890 earned an MA. Through this time, Guerin is reported in the press for various achievements, including her translation from Greek into English of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound.

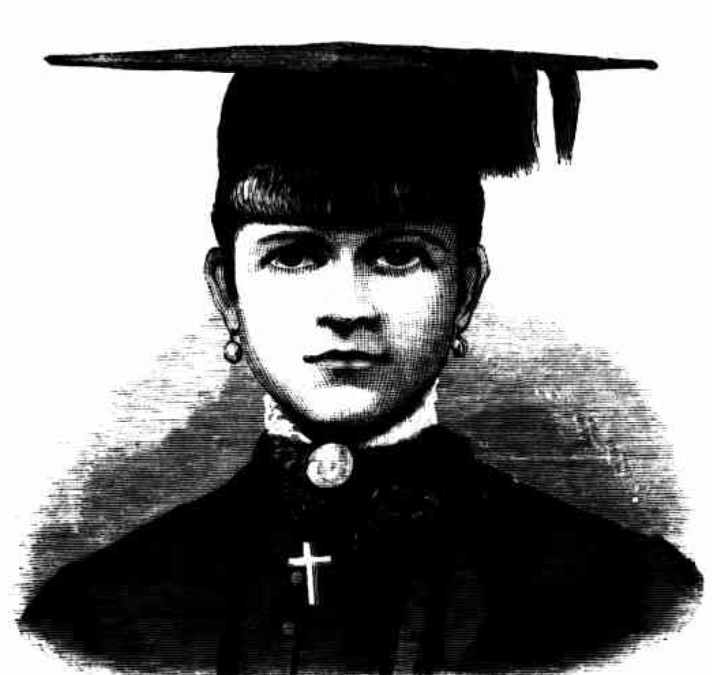

In the early 1880s, Bella attracted the attention of the South-African born Sydney poet Henry Halloran, fifty years her senior. Halloran publicly wooed Guerin in the pages of the Australian town and country journal, publishing the poem, “Impromptu, on seeing a likeness of Miss Bella Guerin MA” in her honour – most likely referring to the picture reproduced above. In 1891, at the age of 32, Bella married Halloran at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Melbourne; the ceremony was reported as “quiet”, evidently due to the recent death of the bride’s mother. Bella championed her elderly husband’s work, submitting a poem for him in 1891 to the Geelong advertiser. The couple moved north to NSW, and in 1892 she gave birth in Newcastle to a son, named Henry after his father. Henry senior died soon after in 1893.

Out of financial necessity, Guerin returned to teaching in the 1890s, firstly in Sydney, then in various places in Victoria, including the University college, Bendigo. In 1909 she taught at the High School for Girls in Ballarat, where she was both owner and principal. Despite having conflicts with the health department, she continued to teach there until 1917.

As early as the 1890s, Guerin was politically active, firstly with the suffragist movement and later with the Women’s Political Association (WPA), co-authoring Vida Goldstein’s 1913 Senate election pamphlet. Guerin was also president of the first Women’s Anti-Conscription Committee, and was initially a dual member of both the WPA and the Labor Party. In 1918, as vice-president of Labor’s Women’s Central Organising Committee, she famously described Labor woman as “pack-horses and performing poodles”, used for fund-raising, but poorly represented when it came to policy decisions. Despite her outspokenness, she was highly regarded by many, one Labor commentator describing her as “always witty, cogent and instructive”, another as a fine orator “with a good delivery, a fine command of words and a fund of satire”. Having drifted from the Catholicism of her birth, Guerin became a rationalist and true socialist, even a revolutionary, and saw socialism as Australia’s future.

In her personal life, Guerin had not remained a widow. In 1909, she married George Darcie Lavender, a man thirty years her junior. One account of Lavender refers to him as also having been a poet, but I’ve found no evidence of his work. He did write to the press in 1910 on behalf of Vida Goldstein, urging people to vote for her, but whether the letter reflects his own political views, or that of his older wife’s, is perhaps open to question. In one meeting of the WPA, Guerin led a discussion on the word “obey” in the marriage vows, and reportedly said, “In nine cases out of ten, it is the man who obeys the woman. Then why retain the shadow when the substance is gone?”

This second marriage was apparently short-lived, though Guerin still referred to Lavender as her husband in 1916 when he enlisted, writing “she thanked God he had gone as a volunteer”. While this was probably intended to reflect her anti-conscription stance, I can’t help reading it in another light. Lavender’s war record name his sister, not his wife, as his next of kin, and after Guerin’s death, there appears to have been no loving tribute from him. By contrast, two of her female friends described Guerin in press notices as their “dearly loved friend”. “Men do not want women with brains as wives,” Guerin declared in 1921. Perhaps that – rather than the massive age gap between she and her husbands – was the root of the problem.

Guerin died in 1923, apparently of cirrhosis of the liver, while living with her son Henry, a doctor, in Adelaide.

Regarding Guerin’s literary output, the AustLit database lists only three of her works, poems published in the 1880s. For our archives, I’ve found several other poems, including ones published under her married names, most of them inspired by the deaths of prominent persons. Guerin also wrote many journalistic pieces, on themes similar to those of her public lectures. It is her poetry, however, that best reflects the trajectory of her political views, her shift from patriotic Catholicism to revolutionary rationalism, from “imperialistic butterfly”, as she described it, to “democratic slug”. Her early poems are learned and weighty, full of classical references and traditional values. Later, the poems have simpler language and are much more didactic at times. The final one I’ve located is a sonnet written in 1913 to Mrs Pankhurst.

A piece published in Table talk after her death gives us a further insight into Guerin’s life:

Educated by her mother, who had had the advantage of many years’ schooling in France and Belgium, Mrs. Lavender was a brilliant scholarly woman, and spoke French as fluently and wittily as her mother tongue, and she was very proud of her University Degree, won in the “dark ages,” when brainy woman were regarded as undesirable blue stockings, and their presence at the University was frowned upon. She was a writer, and her efforts in the press and on the platform helped in a great measure to secure the suffrage for women.

In 2001 Bella Guerin was posthumously inducted into the Victorian Honour Roll of Woman. There she is better remembered for being the first female graduate from the University of Melbourne, and for her political work, rather than for her output as a writer. Her sonnet dedicated to Emily Pankhurst will appear on Friday.

~

References:

A Melbourne wedding, Freeman’s journal, 11 Jul 1891: 15.

Ailsa G. Thomson Zainu’ddin, “The poor widow, the ignoramus and the humbug”: An Examination of Rhetoric and Reality in Victoria’s 1905 Act for the Registration of Teachers and Schools.*

At the Bijou, The socialist, 17 Dec 1915: 1.

“At the Bijou. Should wives obey?” The socialist, 24 July 1914.

Death of Mrs Bella G Lavender, MA, Labor call, 23 Aug 1923: 4.

Death notice The register (Adelaide), 27 Jul 1923.

Family notices, The argus, 2 Aug 1923: 1.

Family notices, The argus, 4 Aug 1923: 11.

Miss Bella Guerin, Illustrated Australian news, 24 Dec 1883: 210. (with portrait)

Mrs Bella Lavender’s husband enlists, Barrier miner, 19 Oct 1916: 2.

On the bank, The socialist, 17 Sep 1920: 2

One of ours”, 19 Sep 1891: 1.

To Miss Bella Guerin, on her attaining her degree of BA, The Ballarat courier, 8 Dec 1883:1.

Mr Henry Halloran CMG, Australian town and country journal 3 Jun 1893: 32.

Prominent people, Labor call, 19 Nov 1936: 5.

Untitled note, Truth, 8 Oct 1921: 5.

Victorian honour roll of women.

“Women as Labor orators”, Northern standard, 23 Oct 1923: 4.

Elizabeth Lhuede first published poems and short fiction in the 1990s while working at Macquarie University as a tutor and research assistant. After completing her PhD, she took a break before returning to Macquarie to teach English and Creative Writing. More recently, Elizabeth instigated the Australian Women’s Writers Challenge and, under the pen-name Lizzy Chandler, has had two e-novellas published with Harper Collin’s Escape imprint (romance and romantic suspense), one of which has been anthologised in print.

Elizabeth Lhuede first published poems and short fiction in the 1990s while working at Macquarie University as a tutor and research assistant. After completing her PhD, she took a break before returning to Macquarie to teach English and Creative Writing. More recently, Elizabeth instigated the Australian Women’s Writers Challenge and, under the pen-name Lizzy Chandler, has had two e-novellas published with Harper Collin’s Escape imprint (romance and romantic suspense), one of which has been anthologised in print.

I have long been interested in the subject of women and university, as women going/ not going to uni often comes up in C19th lit.

I finally discovered that Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide all claim to be the first to allow women to sit for a degree, in1881. As Edinburgh became the first uni in the UK to admit women in 1881 I imagine that was the catalyst.

In writing all this up I too came across that photo, in a history of Melb Uni medical school, I think, and used it in my post.

I think you must have mentioned your interest, Bill, and how interesting Australian states were so quick off the mark. “New” country, fresh ideas perhaps.

I should say I found your write up of her life really interesting, as I knew very little about her, and hadn’t run in to her in my reading on Victorian suffragism. In passing, I have always been pleased that Australian suffragists lined up with the anti conscription movement, and generally were anti-war. Unlike the more famous Suffragettes, though there were anti-war suffragists in England too, with whom Miles Franklin was aligned.

Thanks Bill. I thought Guerin would be up your alley.

Brilliant, as usual! What an interesting life, even just this snapshot you’ve provided here. Like Bill, I am always interested in women and university and the odds they had to overcome in the early days.

Thanks Stacey. I must make sure I’ve added a sampling of her journalistic pieces to our archives. It’s always a thrill to come across progressive thinkers.

I look forward to the poem on Friday Elizabeth.

Great story of yet another fascinating woman. I checked Clare Wright’s You daughter’s of freedom, but she doesn’t appear. Just wondered given your reference to her involvement with Vida Goldstein.

She certainly made some interesting marriage choices. Interesting to consider why there was no one around her own age to attract her. All one can think is that she was a singular person who didn’t follow the crowd!

Finally, that obey thing! Good for her.

I agree, Sue – very interesting marriage choices. What would she have been like in person, I wonder? Thanks for commenting, as always.

I do too … !