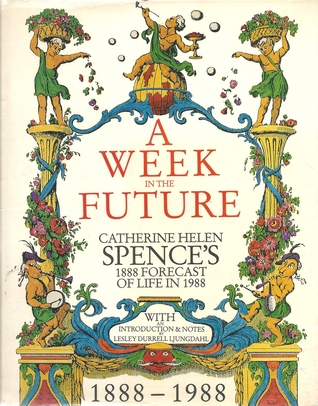

Spence’s science fiction novel, A week in the future, was first published in 1888. We originally intended to publish the following to accompany Bill’s piece on the book in January, but somehow the scheduling got mixed up. The extract is taken from the novel’s opening.

I have often observed that unmarried people, old maids and old bachelors, take a keener interest in old family history, and in the ramifications of the successive generations from the most remote ancestors they can claim, than those who form the actual links in the chain of descent, and leave children behind them to carry on the chronicle. Having lived all my life with a mother who nearly attained the age of a century, and having a strong interest in things past as well as in things present, I have been steeped in memories of old times. I know how middle-class intelligent people lived and worked, dressed and dined, worshipped God and amused themselves, what they read for pleasure and for profit, not only so far as her own recollections could carry the dear old lady, but two generations farther back. In her youth she had lived much with an intelligent grandmother, who could recollect the rebellion of 1745, and the battle of Prestonpans, and had been of mature years during the American War of Independence.

My own mother’s youth had been the period of the gigantic struggle of Great Britain, sometimes single-handed, against the power of the first Napoleon. The older lady had said to her then youthful descendant that no one could expect to see as much as she had seen in her life, which extended from 1734 to 1817, and included the American War, the French Revolution, and the application of machinery to so many of the arts. The grandchild, born at the beginning of 1791, had seen five French Revolutions, and the map of Europe strangely altered; triumphs of art and science, countless in number; steam, gas, electricity, the railway system; mechanical inventions which had revolutionized industry; and the rise of mighty colonies to compensate for the loss of the United States. In the growth of one great colony she had taken a deep personal interest, for she had watched it from the day of very small things in 1839. As we sat and talked together, we would wonder what there could be for me to see that would be equal to what had unfolded before her eyes. Was there to be federation or disintegration? Was the homogeneous yet heterogeneous British Empire to be firmly welded together, or were the component parts to be allowed peacefully to separate and form new states? Was the régime of unrestricted competition and free trade and individualism to be kept up, or were these to be exchanged for protection and collectivism? What was to be the outcome of the Irish Question, of German Socialism, of Russian Nihilism? Was Britain to remain mistress of India, and to keep that dependency? Was she to annex all territory which might be supposed to preserve her open route towards it? What struggle was there to be in central Asia between Britain and Russia? What power was likely to demolish the terrible armed peace of Europe? Such questions as these occupied my own mind primarily–my mother had taken the keenest interest in them all, but latterly she cared less for the questions of the day, and as her health gradually declined, she went further and further back till she seemed to live more in the first ten years of the century than in the more recent past.

When, after a long, wearing, and painful illness, I closed my mother’s eyes–my companionship and occupation both gone at once–I had to consider how I was to take up my life again. I was poorer after her death, because her annuity, which must have made the insurance company the losers, died with her, and I was left with that sort of provision which the world considers quite sufficient for an elderly single woman.

My brother Robert came the day after the funeral to talk matters over with me. “You have had a shock, Emily,” he said, “You would not save yourself any way;–now, you must try to take life easier. What do you yourself think of doing?”

“I mean to stay on here if I can manage it,” I said.

“Don’t attempt to keep house by yourself, it is too expensive, and too much of a tie. Of course, so long as our mother lived, you had to keep a home for her, and to stay in it, but now, if you will not come and live with us, you had better go and board somewhere, or furnish a set of apartments, and that would leave you at liberty. You have not work now for two servants; if you have only one you cannot leave her by herself in the house. Belle says she supposes I cannot persuade you to take up your abode with us.”

My sister-in-law, though in her way an excellent woman, was one of the most abject slaves of Mrs. Grundy, and her ways were not my ways. Their house seemed as full as it could rightly be with their own large family, and I could not in conscience think to occupy their only decent spare room, at present tenanted by the married daughter and her first baby. I was not disposed to go to a little den which did duty for a stray bachelor guest. I clung to a home of my own.

~

Catherine Helen Spence, A week in the future (1888-89) – link to Project Gutenburg Australia