by Florence Blair, “A Victorian girl” (1860-1937)

A tale in which “A Victorian girl” is guided by Laulii, a reteller of ghost stories and Samoa’s first female English-language author. (Originally published as “Samoan bogies”.)

The only sound that breaks the stillness is the splash of the oars and the low roar of the surf on the reef. The tide is coming in rapidly, so the little fishing canoes, whose lights an hour ago twinkled all over the dark bosom of the harbour are safely tucked upon short, the light extinguished and the fishers gone home. It is three hours since we left Vaitele, and we are making little headway because of the strong tide. The rowers seem quite tired out, poor fellows. It is nearly an hour since they sang their last song, and when a Samoan ceases singing he pulls very languidly.

The only sound that breaks the stillness is the splash of the oars and the low roar of the surf on the reef. The tide is coming in rapidly, so the little fishing canoes, whose lights an hour ago twinkled all over the dark bosom of the harbour are safely tucked upon short, the light extinguished and the fishers gone home. It is three hours since we left Vaitele, and we are making little headway because of the strong tide. The rowers seem quite tired out, poor fellows. It is nearly an hour since they sang their last song, and when a Samoan ceases singing he pulls very languidly.

“How far from Apia are we now, Laulii?” someone asks at last. “Not far,” is the reply; “we will be there in half an hour. Are you getting weary of the journey?” “Oh, no!” is the answer, “who could be? It is so glorious. Listen to the music the breeze is making amongst those palms.”

We are very near the shore now, so near that we catch a glimpse of a family gathered at evening prayer through the raised blinds of a house built close to the water’s edge.

We are returning from a four days’ sojourn at some pretty villages far down the island. One was perched on the summit of a high cliff, another nestling on the shores of a quiet little bay, and the other completely hidden by orange trees and flowering reeds along the banks of a noisy, bustling little river. Laulii, our pretty little Samoan friend and guide, is sitting steering in the stern. She has been very quiet for the last half hour or so, and as the boat grates slightly against a prong of coral she starts and shudders.

We look at her surprised. “How foolish I am,” she says, apologetically, “but it is here, just here, that the serpent sinks the canoes. I was thinking of it when the boat bumped, and it frightened me.”

“What serpent, Laullii?” we ask; “do tell us about it.”

Laulii points to a little dark bay, and tells us that under the water there close to the shore, the Samoans believe that a huge serpent sleeps. If the canoes go in too close this monster, part fish and part beast, is disturbed, and enraged it throws its body across the boat and sinks it. The Samoans all swim like fish, but the serpent has the power of thickening and poisoning the water, so that when the body sinks in it, it never rises again. “Of course I don’t believe in it,” says Laulii boldly (now that the dark little bay is some distance behind us), “but it is one of our ghost stories.”

Then we ask Laulii to tell us some other of her weird stories. She becomes very serious, and says, “These I will tell you are true —we all believe them — you must not laugh at them.”

This we promise at once, and Laulii goes on: “We will soon be round the point of Matautu, and then you will see the ghost light off Mulinuu; it is only seen when the tide is full as it is now. You must have seen it many times. It looks like the light of a fishing boat, only it is larger and blue. When all the boats are on shore, and the harbour is dark as it is now, the light springs up, just at the edge of the reef, and burns bright and clear till the dawn comes.

“Years ago, when it was first seen, the Samoans were very frightened; they called it the devil’s light, and begged the missionaries to drive it away. The missionaries said it was phosphorus or something like that, and that it would soon go away. But it will never go away, never, never; it will burn there always when the tide is full, to remind the Samoans how cruel they were once, long ago. My grandfather used to tell me that once a canoe full of people from one of the other islands, who had been driven out of their home by some enemy, came to Samoa and wished to make their home here. But the Samoans forbade them to land, threatened to kill them if they did, and sent them off. It was night, and the tide was very strong. They could not row, they were so worn and tired. When they reached Mulinuu their canoe sank, and they were all drowned. The light sprang up over the place, and it has been there ever since. Look, you can see it now.”

We are slowly rounding the point at Matautu, and Mulinuu is in sight. Sure enough, there is the light burning clearly and steadily off the point. It looks like some solitary fishing-boat; it is the only light in the ha-bour, the men-o’-war having cleared out to sea a day or two ago on account of March, 1889, having been brought rather vividly to mind by a “strong blow” or slight hurricane, which sprang up suddenly.

“Some people say that they have seen ghosts there,” goes on Laulii, pointing to the grim looking skeleton of the German man-of-war, the Adler, lying on the edge of the reef. “I have not seen them myself, but I have heard the story.”

This is certainly not hard to believe, for the feeblest imagination could conjure up ghosts of drowned sailors haunting that dreary wreck-strewn beach. In high noon, when the sun turns the water into a sea of gold, and the harbour is alive with tiny craft, the sight of the ribs and spars of great ships which are scattered about saddens and disturbs one. But at night, when the wind is stirring the palm trees on shore into all sorts of weird whisperings, and the harbour is dark — as it is now — the scene is ghostly in the extreme. In spite of ourselves we feel creepy, and sit close together, our voices sinking to whispers.

Every part of Apia Harbour is full of tragic recollections. Just beyond us is the spot where the Vandalia disappeared in the great hurricane in 1889. One moment the watchers on the bench saw the ship flung high on the crest of a great breaker, and the next moment she was tossed under the shelf-like edge of the reef, leaving not so much as a spur to mark the spot.

Then Laulii tells us a romantic story of a deserted maiden, who drowned herself not far from Apia, her ghost, holding a flaming torch, rises from the water at mid-night, and peers into the faces of passers-by, trying to discover her faithless lover. This youth, evidently, has been wise enough to keep away from the part of the beach the ghost walks, for it is over fifty years, we are told, since the tragedy occurred, and the ghostly maiden is still on the look-out.

All these uncanny tales have really made us quite nervous, and we are delighted when the boat is pushed alongside the tiny wharf, and we clamber up the shaky steps, and hear Jack’s cheerful voice telling us he has been expecting us for hours.

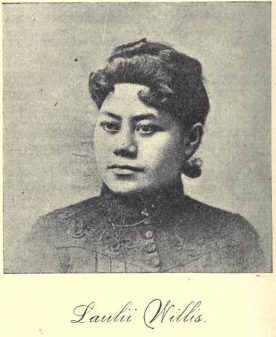

Laulii, who has been our guide on the occasion, is, you must know, a great personage in her way. Her father was a chief at the village of Laulii, after which she was called. When little more than a child she married an American, who took her to America and had her educated. She is very pretty and fascinating, and, wonderful to relate, her American training has not spoilt her in the least, for she is as simple, frank and generous as any Samoan in the island. She has the distinction of being the first Samoan to write a book in English, and a very charming book it is too, written in her own graceful, simple English, full of poetic feeling and warm patriotism. Even Jack, who really seems to feel slighted if we are out of his sight for an hour, said when we told him we were going to dispense with his valuable company and conversation for a time and go on a malaga with Laulii, ” Oh, that is all right

Laulii is my relash (relation). She cleverest woman in Samoa. Samoan woman, I mean,” he added gallantly.

Laulii lives in a Garden of Eden sort of place some miles from Apia, on the road to Vailima, R L Stevenson’s place. The Vaisigago, a glorious river, runs through the gardens. Part of the land is laid out in approved civilised fashion, but the rest is planted by the hand of nature, and is just a jungle of palms, orange trees, mangoes, and gorgeous coleus. Built in the civilised part of the ground is a European house, so elegant and complete in detail that it includes a piano, a sewing machine, and “pigs in clover.” Laulii is immensely proud of this home of hers. She and her hand-maidens clean and tidy it with scrupulous care every morning, and then scuttle off to a dear old native house close to the river in the jungle at the back, and remain there for the rest of the day. She tells now with much laughter how terrified she was of the first white man she saw when she was a tiny child. He was a missionary, and was strolling along with a huge white umbrella spread (an article she had, of course, never seen before). With a scream she rushed into a bank of high reeds, and remained there trembling and crying for hours, till her mother found her nearly dead with fright. The white man is held up as the bogy to Samoan children just as the “black” man is to white children, and Laulii tells how, when she was disobedient to her parents, her mother used to say, “The white man will come all take you, “and this threat always frightened her into good behaviour.

In spite of her nine years in America, she seems very much at home down at her own village, telling her numerous nephews and nieces of the peculiar ways of the populace and the wonderful things she saw when she went away in the “big canoe.”

~

References:

“A Victorian girl”, “Samoan bogies,” Argus, 13 Aug 1892: 13.

Authorship established in interview: “La Quenouille” [Mary Hannay Foott], A woman journalist and story writer: interview with ‘a Victorian girl’, Queenslander, 2 Nov 1895: 844.

Image sourced from: Laulii Willis, The story of Laulii, ed. W M H Barnes (San Francisco, Joseph Winterburn and Co, 1889)

Wonderful story telling tales of yesteryear and describing fully in her words the places she knows best

Thanks for commenting, Kerry. It’s a good one, isn’t it? And for such a young writer. I wonder what Blair/Baverstock might’ve achieved if she’d continued with fiction, rather than journalism and editing.