by Whispering Gums

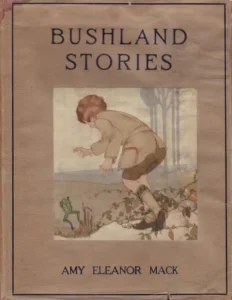

![]() Two months ago, we introduced Amy Mack, a popular Australian writer in the early decades of the twentieth century. In this post, we focus on one of her best known books, Bushland stories

Two months ago, we introduced Amy Mack, a popular Australian writer in the early decades of the twentieth century. In this post, we focus on one of her best known books, Bushland stories

To recap our first post on her, Amy Eleanor Mack (1876-1939) was a writer, journalist, and editor – and sister of Louise Mack (whom we’ve featured here before). Her subject was nature, and she wrote about it in newspapers and books, for adults and children. Mack’s first publications were two collections of essays, A bush calendar (1909) and Bush days (1911), which were compiled from articles she’d written for the Sydney Morning Herald. She also several children’s books, of which Bushland stories (1910) and Scribbling Sue, and other stories (1915) were probably the most popular. All up, Wikipedia lists 14 books, many of which were first published in newspapers, but all of which have titles suggesting nature, like The Fantail’s house (1928) and The gum leaf that flew: And other stories of the Australian bushland (1928).

Bushland stories

Nature writing has a long tradition in Australian literature, and we made that point in our first post on Mack by quoting from Australian ecologist Manu Saunders’ blog:

Australia has a wonderful heritage of nature writers, many working before nature writing was ‘a thing’. The national collection of Australian children’s books about native wildlife is inspiring. Even more inspiring, many of Australia’s best nature stories were written in the early-mid 19th century, and mostly by women.

One of those women was Amy Eleanor Mack. Another, earlier one was the pioneering Louisa Atkinson on whom we posted last year. Bushland stories was one of three collections of stories for children that Mack published in 1910, the other two being Waterside stories and Birdland stories. Bushland stories was reprinted/republished through the 1910s, 20s and 30s, and, it appears, as recently as 1987 and 2017. Rebekah Ward’s 2018 Master’s thesis, Publishing for children: Angus & Robertson and the development of Australian children’s publishing, 1897-1933, in which she says that Bushland Stories “became so popular that it was reprinted eleven times by 1940” (from Wikipedia)

One of those women was Amy Eleanor Mack. Another, earlier one was the pioneering Louisa Atkinson on whom we posted last year. Bushland stories was one of three collections of stories for children that Mack published in 1910, the other two being Waterside stories and Birdland stories. Bushland stories was reprinted/republished through the 1910s, 20s and 30s, and, it appears, as recently as 1987 and 2017. Rebekah Ward’s 2018 Master’s thesis, Publishing for children: Angus & Robertson and the development of Australian children’s publishing, 1897-1933, in which she says that Bushland Stories “became so popular that it was reprinted eleven times by 1940” (from Wikipedia)

Reviewing the book in 1910, Sydney’s The World’s News claims that “the Australian book of stories for young Australians has at last been written”, and describes it as a “collection of fables, allegories, fairy tales, or whatever one chooses to call them”. Whatever they are, the reviewer argues that Mack had “created a folklore for young Australians”:

The waves, winds, hills, and streams are personified; the birds, beasts, and fishes all act and speak like rational beings; while trees and flowers play an animated part, and real Australian fairies occasionally interpose quite like their old world congeners. But everything is Australian, and, incidentally – though this never seems the object – a mass of information about the country, its fauna and flora, is included in the matter.

This News goes on to say that the inclusion all this information means that “even the grown-ups who read the stories – and they will be very many” will learn more about Australia’s flora and fauna than they ever knew before. And, the News could be right.

Bushland stories contains twenty-five stories, with titles like “The discontented stream”, “The white herons”, “The vain thornbills” and “The leaf that longed to be red”. The opening story, “The wave”, commences with:

Out on the depths of the deep blue ocean the Wind went wandering. He crept gently over the sleeping water, scarcely disturbing it as he passed. He was looking for some Waves to play with, but there were none to be found.

The water, you see, was “smooth as a millpond”. The story goes on to describe the life of a little Wave who has one short joyful day playing with the Wind, before being taken back into the sea. A death story in fact, which is interesting for the opening story in a collection for children. The next story “The little angler” is not about a young fisher, as I suspected from the title, but about an angler fish. He is ridiculed for his ugliness, but with the support and guidance of his friend, the Seaweed he gets his own back at the end. Seaweed says, “they have learned that it does not do to laugh at other people’s appearance”. It reads, in other words, like a more traditional children’s story with a moral.

However, the aforementioned News says “The moral or lesson of every story is good, and this without the suspicion of any preachiness, which many youthful readers shy at.”

My edition of this book was a 1923 school prize for my late father-in-law, and it includes “47 illustrations by Joyce Dennys”, which are different from those in the earlier editions. Dennys was, says Wikipedia, an English cartoonist, illustrator and painter, and she apparently worked as an illustrator in Australia between 1919 and 1921. Books published then did not always include the publication details that we expect now, but I believe my father-in-law’s edition was probably published in 1921, because there is a review of it in Sydney’s Freeman’s Journal in early 1922, on 5 January. The short review is positive, as most reviews of Mack’s works seemed to be. It starts

Amy E. Mack knows how to get to the hearts of children through the animals and birds and flowers which she brings so delightfully into her stories, and which, as well as interesting the young mind in fairies and fairyland, create a love and an understanding of the beautiful things of the Australian bushland. Her latest book is for children — “Bushland Stories” — all of them delightful tales, as arresting to grown-ups as to youngsters, yet given in the simplest and most “understandable” language.

Again, there is that reference to the fact that adults will enjoy this book as much as children will. The review also specifically mentions the “delightful illustrations by Joyce Dennys”, and makes the point that Amy Mack knows how “to captivate the childish mind”. Further

she disguises her technical knowledge of birds and flowers and animals under the most attractive and ingenious devices. She is an ideal companion with whom to wander hand in hand through the bush, pointing out in her whimsical way, all the things that children love to see and to know, and teaching them wise lessons of flower-lore and bird-lore under the semblance of merry tales.

In “The Wave” we are taken to Bondi Beach. In the third story, “The discontented stream”, the scene is set with descriptions of local flora and fauna, like lillipillis and sassafras, satin birds and magpies. Another story, “The tale of Tibbie” is set on the Great Barrier Reef, while in “How the flower fairies helped”, we have Wattle Fairy and Correa Fairy, and characters called Bauera and Eriostemon. This continues throughout the stories, some in named settings, some in more general bushland, but always referencing Australian life and nature.

It is for all these reasons that Amy Mack and her writing have a place in discussions of modern eco-literature, and why, it seems, Bushland stories continues to be published.

Sources

Amy Eleanor Mack, Bushland stories, Angus and Robertson, 2nd ed., 1914 (Available online at the Internet Archive)

Nancy Phelan, ‘Mack, Amy Eleanor (1876–1939)‘, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1986.

Manu Saunders, “The wilderness: Amy Eleanor Mack“, ecologyisnotadirtyword.com, 4 March 1917

Rebekah Ward, Publishing for children: Angus & Robertson and the development of Australian children’s publishing, 1897-1933, Master’s thesis, 2018 (found via Wikipedia’s Amy Mack article)

Newspaper sources from Trove are hyperlinked in the post’s text.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whispering Gums, aka Sue T, majored in English Literature, before completing her Graduate Diploma in Librarianship, but she spent the majority of her career as an audio-visual archivist. Taking early retirement, she engaged actively in Wikipedia, writing and editing articles about Australian women writers, before turning to litblogging in 2009. Australian women writers have been her main reading interest since the 1980s.

That Bushland Stories cover looks familiar. Is that your copy, illustrated by Joyce Dennys? I reckon I have a book with a similar cover, but it’s probably down the bush with my grandchildren.

No it’s not actually Bill. Mine has gorgeous birds. This is a modern edition but is close to my cover … https://bookgrocer.com/products/9780207148521-secondhand-bushland-stories I’m en route to Melbourne so away from the book!