by Michelle Scott Tucker

Michelle, who would have liked to lead a Billabong life, and in fact has always had a horse or two to keep her company, introduces us here to her life-long love of the Billabong books.

Michelle, who would have liked to lead a Billabong life, and in fact has always had a horse or two to keep her company, introduces us here to her life-long love of the Billabong books.

The books, old and musty, were stashed at the back of a cupboard for want of shelf space. They’d been there for quite a while. A friend of my mother had owned them once, but had passed them on, suggesting vaguely that “Michelle might like them.” I was in primary school, probably, an avid reader but not much tempted by the heavy, old-fashioned tomes, with no dust jacket or blurb to hint at what lay within.

Not tempted until boredom drove me, one weekend, to dig out those books. Reader, I was transported.

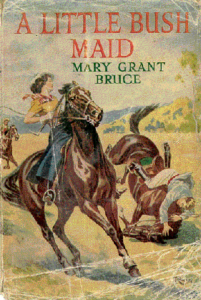

My newest favourite character, Norah Linton, lived with her widowed father and beloved older brother on a huge and prosperous farming property, called Billabong, in country Victoria in the early 1900s. And oh what jolly adventures they had. I would eventually discover that there were 15 books in the series (the cupboard held maybe only 5 or 6), but even within the first, A Little Bush Maid (1910), heroine Norah at the age of 12 manages to save, quite separately, the lives of two men and a valuable flock of sheep. One of the men was a deeply grateful lion tamer (!) but her family seemed more impressed by the saving of the sheep. It’s all very Enid Blyton meets the Australian bush, with effectively parentless children going on picnics and having improbable adventures. In one of the later books, they discover enough gold to start their own mine… Norah, however, was always appropriately modest about her efforts, and rightly so, because far more important to her – and to me, marooned in deepest darkest suburbia – was the ordinary, day to day life of the farm.

On Bobs, her perfect pony, Norah raced her brother Jim and his two best chums across the paddocks. Accustomed to working beside her father, Norah mustered cattle, thought nothing of driving a cart seventeen miles to the nearest town to collect the mail, looked after a menagerie of pets, and fished in a nearby river. Norah is, in short, a paragon but she is painted with such love and good humour that her character fairly lifts off the page. And, in a very Australian way, the books are genuinely funny. The children are realistically prone to pranks and teasing. They fall in the water, they fall off horses, and the boys fall asleep in the drawing-room after dinner – only to be gently awakened by Norah pouring a “trickle of water on their peaceful faces. Peace fled at that, and so did Norah!”

On Bobs, her perfect pony, Norah raced her brother Jim and his two best chums across the paddocks. Accustomed to working beside her father, Norah mustered cattle, thought nothing of driving a cart seventeen miles to the nearest town to collect the mail, looked after a menagerie of pets, and fished in a nearby river. Norah is, in short, a paragon but she is painted with such love and good humour that her character fairly lifts off the page. And, in a very Australian way, the books are genuinely funny. The children are realistically prone to pranks and teasing. They fall in the water, they fall off horses, and the boys fall asleep in the drawing-room after dinner – only to be gently awakened by Norah pouring a “trickle of water on their peaceful faces. Peace fled at that, and so did Norah!”

First published between 1910 and 1942, Mary Grant Bruce’s hugely popular Billabong books influenced, alongside Banjo Patterson and Henry Lawson, our concepts of The Bush and Australian identity. Her work “was characterised by fierce patriotism, vivid descriptions of the beauties and dangers of the Australian landscape, and humorous, colloquial dialogue celebrating the art of yarning.”

The Billabong books, and Bruce’s two dozen or so other books for children, championed the values of independence, mateship, hard work (for women and children, as well as men), and bush hospitality. The children age as the series progresses, and several of books of the series follow Norah’s brother Jim, and his best mate Wally, as they serve in WW1 – so even the ANZAC spirit gets an airing (even though they served in the British Army, rather than the Australian one – it all makes sense at the time).

But, and sadly there always seems to be a but, my beloved Billabong books belong very much to the era in which they were written.

Almost every writer I know cites Enid Blyton as one of their favourite childhood authors. She transported them in a way few other writers could. But almost every writer I know is also sorrowfully aware that once you’ve grown up there is no going back to Blyton’s magical worlds. The racism, the class barriers, the gender stereotypes are just too distressingly obvious to make Blyton an enjoyable adult read. And so it is for Billabong.

A footnote to later editions, published in the early 1990s, noted that “Some of Bruce’s earlier works are considered to have had offensive and dated content, particularly in regards to racial stereotypes of Australian Aborigines and Chinese and Irish immigrants, and her earlier belief in the theory of Social Darwinism. More recent reprints of the Billabong series have been edited to remove controversial material.” I haven’t looked into those later editions, and frankly I’m not sure how all the ‘controversial material’ could possibly be removed without materially altering the story, because there certainly is a lot of it.

The Linton family are very much lords of their Australian manor, ruling in a benignly patronising way. The house (large enough to have ‘wings’) is staffed by a doting cook and various ‘girls’. The decorative front garden is maintained by a Scotsman, the vegetable garden and orchard at the rear by Chinese Lee Wing (and oh isn’t his silly accent funny!) Numerous unnamed men work the farm itself with one of them, called Billy, seemingly assigned to be the children’s personal slave. Billy is never, ever described without with an adjective like “Sable Billy” or “Dusky Billy” or “Black”. And in case the reader hadn’t quite caught on, he is also variously described as careless, lazy or – just once – as a n—-r. At 18 years of age Billy is older than the children and, according to Norah’s father, the best hand with a horse he’d ever seen, yet the children casually order him about and call him Boy. Billy, like every 18 year old bossed by a 12 year old girl, living without friends or family, and with no girlfriend in sight, seems perfectly content with his lot.

The class barriers are there too, in the patronising colloquial dialogue and simply in the assumptions of the day. Norah, left at home for several days while her brother and her father are away, will inevitably be “desperately lonely with only the servants to talk to.” A stranger who might otherwise be mistaken for a tramp is immediately identified, when he speaks with a cultured accent, as “not your ordinary sort of swagman.”

Crucially, though, gender stereotypes are played with a very light hand. Well, sort of. We are talking about books written a hundred years ago.

Mary Grant Bruce (1878-1958) was herself born and raised in country Victoria, in East Gippsland. At the age of twenty she moved to Melbourne and fairly quickly made a modest living as a freelance journalist. Her first Billabong stories were serialised in the Leader, before being published in London by Ward, Lock & Co. The success of the first led to an ever-increasing demand for more, until Bruce was producing a book each year, in time for Christmas. She didn’t love the Billabong series quite as much as her fans, and she eked them out – one year producing a Billabong book, the next a stand-alone title, and the following year another Billabong book. She married an army officer, lost two of her three children in tragic circumstances, and lived variously in Ireland, Australia and England. She was, in her day, one of Australia’s most successful writers. She has, in this day, very nearly been forgotten.

Bruce was a typical country conservative who, just as many do now, believed that men and women were equal, but necessarily separate. Bruce herself wrote that “the position of women in Australia today is largely what the pioneer women made it. They took their place definitely, equal fellow-workers with men, the more secure because no one had any time to talk of women’s rights.”

In Norah, Bruce epitomises the self-reliant country woman who can hold her own with a man, without becoming (or threatening) one. Norah is, categorically, the star of the Billabong show. She loved music, and was a good cook but “lived out of doors, followed in Jim’s footsteps wherever practicable (and in a good many ways most people would have thought distinctly impracticable) and spent two-thirds of her waking time on horseback…her chosen pursuits brought her under the discipline of the work of the station…she had all the dread of being thought “silly” that marks a girl who imitates boyish ways.”

For Norah, her brother and father are at the heart of all she does and loves. Male activities are valuable and worthy, female ones much less so. Norah “had no little girl friends” partly because none were closer than the town seventeen miles away but mainly because “little girls bored Norah frightfully.” Little girls, apparently, are prone to prattle about dolls, and play dress up and ‘ladies’. “When Norah spoke of the superior joys of cutting out cattle or coursing hares over the Long Plain, they stared at her with blank lack of understanding. With boys she got on much better.”

Reader, c’est moi. Or so I wished. While I lacked a prosperous county estate and a fine, well-bred pony full of life and go (yet without the smallest particle of vice), I spent many happy hours with Norah enjoying hers. Her esteem of male pursuits echoed my own, as did her disdain for most things girlish. I too was a little girl always seeking her brothers’ and father’s approval. I sobbed when Norah’s pony died, and was on tenterhooks until Jim and Wally came home safe from the war (spoiler alert – they come home safe from the war). Norah and the boys grew up and married but they never really changed at all, and I loved being part of their world.

But it’s a world long gone now, if it ever was, and that’s for the best.

The Billabong books, in their original unedited form, remain readable, funny and even entertaining. They are also profoundly disturbing. Their value now is more for their insights into a not-so-distant historical period and mindset, rather than as a book that a modern child might thrill to read by torchlight, under the covers.

The Billabong series by Mary Grant Bruce (1878-1958), published by Ward, Lock & Co. of London and Melbourne.

- A Little Bush Maid (1910)

- Mates at Billabong (1911)

- Norah of Billabong (1913)

- From Billabong to London (1915)

- Jim and Wally (1916)

- Captain Jim (1919)

- Back to Billabong (1921)

- Billabong’s Daughter (1924)

- Billabong Adventurers (1927)

- Bill of Billabong (1931)

- Billabong’s Luck (1933)

- Wings Above Billabong (1935)

- Billabong Gold (1937)

- Son of Billabong (1939)

- Billabong Riders (1942)

.

Michelle Scott Tucker who lives near Melbourne with her family, a dog and some horses, is the author of Elizabeth Macarthur: A Life at the Edge of the World (2018); and the co-writer with Aaron Fa’Aoso of his memoir So Far, So Good (2022).

Thanks, Michelle. You’ve brought back memories. I was introduced as a child to the Billabong books initially by my mother (a country girl), and later by my country cousins whose library shelves became my sanctuary during hot, dry and dusty school holidays. The romance of the bush – and Norah’s spirit and agency – appealed far more than the reality!

Norah is a terrific character, I still love her. Even considered naming my daughter Norah (for about 5 seconds)!

Oh, Michelle – you’ve brought back such memories for me! I was a child in the 1950s, and I absolutely adored the Billabong books. I must have read the first one, A Little Bush Maid, when I was about nine or ten. I received the rest of the series, in order, for every subsequent birthday and Christmas until I had the full set. I read them over and over again until I could recite whole passages by heart. Norah was my heroine and her life was my dream. At the age of 20, in 1965, I married a grazier’s son and headed off happily for a life in the bush, looking forward to galloping around the property with my husband, mustering sheep and cattle and having a wonderful time. Alas, I soon discovered that this was not his, or his family’s, vision for me. My role was to breed children, and I was expected to stay in the kitchen being an obedient (and silent) slave. After six or seven increasingly miserable years I took my kids and ran away. I blame Mary Grant Bruce for the whole fiasco!

Oh no – but what a lucky – indeed, sensible – escape. And honestly, if a grazier’s son had asked me to marry him when I was twenty, I’m sure I’d have been in the same situation (and for much the same reasons!)

Thanks for your understanding, Michelle!

Like Norah, I was a country girl, I loved the Billabong stories; also “7 little Australians” and its sequels. They made me feel I belonged in Australia.

I lived on a farm, with dairy cattle near the house and grazing bullocks further away. I was not involved in the dairy, but when my brother went off to boarding school for 3 years, I became Dad’s right-hand man looking after the bullocks. I was 9 years old.

That taught me to be independent, and self-reliant. It also taught me gender roles (I could be involved in mustering, but not branding, or castration. Then I was banished to the house. If other men came to visit while we were working stock, again I was banished. I guess Dad was a bit ashamed that he needed his little daughter to help.) But I loved the life.

I did pick up a copy a few years ago, and was appalled by the racism. It has spoiled my memories of a happy childhood.

I’m glad you had such a happy childhood – I’d have given almost anything to be in your shoes when I was nine. And like you I was shocked, actually, during my recent readings by MGB’s racism. And almost equally shocked to realise how I’d not noticed it at all when I was reading as a child and teen. Perhaps, then, I AM getting wiser as I get older…

I loved the Billabong books as a child. Some of them must have been early editions because they belonged to my mother. They were lost in a fire when I was a teenager having been stored in my grandmother’s shed. My mother Marjorie Sutton was a popular radio personality at 3TR Sale so I was surprised to see Mary Grant Bruce had been born in Sale. I am an Aussie living in Georgia, U.S.A. Would love to obtain some of the Billabong books. Would you know how I could do that?

Hi, Judith! As far as I can discover, the Billabong books are not currently in print (happy to be corrected on this). However, used copies often turn up for sale on websites such a eBay, Amazon, Thriftbooks, and other online booksellers. Just do a search for each individual title and see what pops up. Good luck – I hope you find at least some of them!

That would be great. I would love to read them again. My Uncle Joseph Armstrong served at Gallipoli with the Light Horse Brigade. He was a burglar. A great Uncle Arthur Cheshire, an Aussie, was killed in France fighting with the British. Buried in France, so Jim and Wally’s wartime experience was meaningful to us. Thank you for your reply.

Uncle Joseph Armstrong was a Bugler not burglar on Gallipoli in WW1! He sounded the various notifications to the troops on the bugle.