by Ethel Mills Primrose (1870-1951)

“The Chee child: a story for children” first appeared as “The China child” in 1902, and was revised and reprinted under a different title in 1905 in Pall Mall magazine. The Pall Mall version is reprinted here, not only because it contains illustrations and is not readily available to the public, but also because it provides a version which can be compared with the original (which did not, I might add, declare the story was for children).

Note: When reprinting archival stories which contain racially sensitive and/or offensive material, the temptation is to edit – and sanitise – them for a modern audience. That temptation has been resisted here. Australia has a history of racism, and it was especially rife against ethnically Chinese Australians at the time of the story’s publication.

Perhaps it was because Carola had been especially told not to play with the “Chee-chee child,” as young Eurasians are termed, that she showed such an intense desire to do so.

Perhaps it was because Carola had been especially told not to play with the “Chee-chee child,” as young Eurasians are termed, that she showed such an intense desire to do so.

Also, there is undoubtedly much in the attraction of opposites; and had you hunted the vast continent over you could scarcely have found two children more different in appearance, character, and the circumstances of their surroundings, than Lily Wang Sen, the slant-eyed, stolid little Eurasian, and Carola Chesney-King, the well-cared-for, only daughter of wealthy northern people, who were wintering in Brisbane at the handsome private hotel known as “The Crotons.” And it was only in Brisbane, dear, beautiful, dirty, river-embraced Brisbane, that the lines of life of two such widely diverse atoms of humanity could run together, cheek by jowl, so to speak. Carola was a wise, thoughtful soul, for all her eight years, and was always trying to solve problems. The hardest she ever tackled, perhaps, was how to win the love of Miss Lily Wang Sen (to whom her heart had gone out unreservedly) without disobeying her parents by playing with the fascinating “Chee child” or her horde of tan-faced sisters and brothers.

Many a time, when she grew tired of piling the falling Jackaranda blossoms into soft lilac heaps for her dolls to lie upon, she would creep to the iron fence and look through a peephole at the Wang Sens’ backyard, where, among the weird Anglo-Chinese heaps of rubbish, the yellow children sometimes strayed; and through it also she had a glimpse of a window over which a decrepit art muslin curtain hung (and is there anything else that deteriorates so completely, so raggedly and so unartistically as art muslin?). Now and then the wind blew it aside, and (oh, joy of joys!) she more than once caught sight of Mr. Wang Sen pinning up his pigtail with real hairpins, or eating his dinner from tiny green bowls with chopsticks!

At such times her heart grew heavy, and she compared the beautiful untrammelled, unwashed lives of her neighbours to her own starched, beribboned and soap-and-water existence; above all, she envied them the plentiful and never-ending supply of sloe-eyed babies. Lily was only about her own age, yet she was the eldest of nine little Wang Sens, including two sets of twins!

“Mother dear, why don’t we have lots of babies? shall I ask the China girl to spare us one of theirs? Mrs. Wang Sen often says she wishes that half o’ them were ‘laid out,’ – that means dead, you know.”

Barbara King raised her arched eyebrows in shocked astonishment, and came back to earth and the wistful, muslin-skirted mite at her knee.

“Carola!” she cried, “you must not go near the fence: what is Maria thinking about to allow you to hear such language? That is the worst of Brisbane, every decent place has a fringe of slum-dwellers!”

Carola laid her golden head against her mother’s white draperies. “Just one baby, mother,” she pleaded, – “the third youngest: it is such a darling.”

Barbara loved her husband so intensely that there was little surplus affection left for the child: some natures cannot hold two idols at once; but she tried to do her duty to the little one, to understand the deep intense nature so akin to her own – to guard, if possible, the child from a like fate to her own; and so she put her book aside and strove to follow Carola’s imaginings.

“Are you lonely, chick? shall I send for Robbie Bennet or some of your other little friends to play with you?” she said anxiously, a puzzled look in her beautiful near-sighted eyes.

“No, dear, I don’t think so: Robbie isn’t interesting, – besides, he is too old. I want to play with Lily, the Chee child, most of all; but next to her I want a baby, a real one that crawls about and can’t stand, and eats leaves and sand and dead bees.”

“Good gracious, child, how old-fashioned you are! But I cannot let you play with those Chinese girls; and I can’t get you a baby – how can I?”

“No,” said Carola soberly, “perhaps you can’t; but I must love something.”

“You quaint mortal! haven’t you got your toys, and your dog, and all your nice little friends – and mother?”

“Yes, mother, and you have got me; but I’m not quite enough, am I?”

Barbara flushed, for the unconscious arrow had gone home.

“But she is such an awful little thing – so dirty, so uninteresting. Carola, how can you want her?”

“I don’t know – but I do want her so badly; and she did have a bath once, because I heard her say so.”

“Darling, mother would go crazy if anything happened to you, and she knows best when she tells you not to go near them. Besides, you must never love anything too much: do you hear, Carola?”

She often made speeches like this one to the child, which accounted perhaps for Carola’s own wise saws, but she dropped these warnings of worldly wisdom on purpose: at least Carola should not be handicapped in the race of life with a training of idealism, as she had been. She was often sad at heart when she saw how like herself the child was growing – the same passionate capacity for all-absorbing and faithful love, and, alas! the same clear brain that would spy the feet of clay, however enwrapped the idol was – yes, and the heart that would love still in spite of the brain’s discovery.

“She would have one advantage over me,” the mother thought: “she is pretty.”

And Carola had inherited her father’s good looks, Barbara was plain except for those wonderful eyes, and her only other charm lay in a certain delicate refinement of physique – which, however, did not appeal to Gilbert King at all.

He was coming along the path now; and at sight of him Barbara’s resolution, to read and amuse her little girl, fled.

“Run away, dear,” she said; “father is coming to take me out to lunch.”

Carola melted into the white and lilac Francesca bushes, like the sprite she was; and Gilbert began to speak at once, a tender inflection in his voice – the best asset he had next to his good looks – for the two combined had gained him a lifelong love and an heiress at the same time.

“Little wife, you look very tired this morning: I noticed your eyes at breakfast. You will have neuralgia if you overdo it – so I countermanded the lunch.”

Her eyes darkened with disappointment. “I am not tired, Gilbert; it is such a beautiful day, and I hear the flame trees are all out in the gardens; besides, it is our wedding anniversary, and it would be nice to spend it together.”

“Nice!” repeated the man, – “it would be heaven on earth, sweetheart. But you have no idea of the heat outside; you could not stand it – you are not fit to go out, Barbara. I know better than you do, and you are too precious for me to let you take the risk.”

Barbara clasped her frail hands, for which the glorious rings seemed too heavy, behind her head. “Perhaps you are right,” she said, “and we can be together here just as well; every one is at the regatta, and we have the garden to ourselves.”

But she spoke hopelessly and lifelessly, for she knew just what was coming. Sometimes she wondered if he guessed how much easier it would be for her if he were straightforward even in his meanness.

“I never had any luck,” he said laughingly. “If I had only known you were alone, that all the other women had cleared out! – but I thought you had friends to see you, so I closed with Monty Bell’s invitation to make a fourth at a luncheon party. It really is annoying, confound him.”

“Monty Bell! how odd! he always asks me. Is it a man’s affair only?”

“No, that is the trouble: Florence Massingbird is dining with him. Others may call on her here, but I don’t care for my wife to meet her.” And Gilbert’s air of virtuous disapproval was worth seeing.

“We men of the world––” he began again, but his wife interrupted him hastily. Gilbert in a “moral censor” mood was more than even she could stand.

“Yes, I know, and if all you say is true, I suppose I shouldn’t care to know her – whatever others may do; and if you are going, it is a quarter to one now.”

And then he left her, and the ancient lady and the companion who had been doing fancy-work together on the balcony watched the close of the scene with interest.

“How devoted to her he is!” said the latter romantically. “How one pities any man tied to a lackadaisical piece of goods like that!” And possibly she voiced the opinions of most of the Chesney-Kings’ friends when she said it.

Meanwhile Carola had solved her difficulty, and had managed to attract and to attach Lily Wang Sen’s interest. Gifts of dolls and toys and flowers, pushed through a hole in the fence, had failed in their object. The Chinese children received them apathetically, and seemingly preferred a dead sparrow or such-like treasures, delved from the rubbish heaps in a vacant allotment, to all Carola’s gaily painted playthings. Then came the happy thought to bring her eleven-o’clock luncheon of fruit and cake to the shrine; and Lily Wang Sen was there to receive it as regularly as clockwork, while the nurse, who adored her charge, was delighted at the enormous appetite so suddenly developed, although she marvelled somewhat at Carola’s predeliction for eating it in the shade of the Francesca.

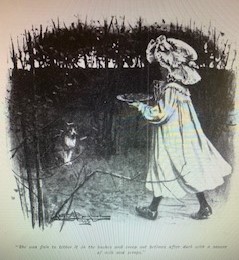

Sometimes one or other of the Croton dwellers would give a garden party, when smart carriages full of beautifully dressed people drew up before its gates; and the blear-eyed women (who seemed to spend all their days in teagowns and curling-pins) would stroll to the fence to criticise and compare, while their little ones peeped through the palings; and from these entertainments Carola always managed to secure a goodly pile of cakes and bonbons, which her neighbours received joyfully and devoured at their leisure, after the guests had departed; for even more than good things to eat, the slum dwellers loved a pageant, whether it took the form of a party, a fire, or a fight; and gradually Carola’s persistent solicitude raised a faint sparkle of gratitude in Lily Wang Sen’s heart, for she made a return present – no more or less than a meagre yellow kitten, which she pushed through the hole in the iron fence with the aid of a broom. Carola’s eyes sparkled at the compliment when the Chee child’s round face appeared at the opening and the wooden voice told her, “The cat’s to keep.” But she found it rather a white elephant: she knew just what reception these town cats got from the nurse, so was fain to tether it in the bushes and creep out betimes after dark with a saucer of milk and scraps of meat for its delectation, or smuggle it into her cot, only on the girl’s night out, until the weird-looking, wheezing animal chose to give up the ghost. And whether it was these nocturnal excursions, or the fact that the kitten probably suffered from the dread disease which slum-cats are apt to do, the time came when Barbara put her idol in the background for a space and spent all her days with her child, who lay fighting for breath in the grasp of diphtheria. The carriages of the cleverest doctors in town drew up at the Crotons now, but the busy coming and going of guests went on just the same, and if the angel of death towered over a distant wing of the creeper-covered house, there was mirth and to spare in the rest of it.

Gilbert spent what was perhaps the most uncomfortable time of his life just then; but it was over soon enough, for on the tenth day Carola gave up the unequal battle and closed her eyes for ever on the limited stage of her existence, and it was of the Chee child she babbled to the last as long as her voice was left her.

Gilbert spent what was perhaps the most uncomfortable time of his life just then; but it was over soon enough, for on the tenth day Carola gave up the unequal battle and closed her eyes for ever on the limited stage of her existence, and it was of the Chee child she babbled to the last as long as her voice was left her.

“The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away.” “Be sure it is all for the best.” These, and other sentences which conventionality decrees shall be said to the sufferer from fate’s arrow, were said to Barbara; but the last one only had meaning for her, when, as the little flower-heaped coffin was carried down the winding path, over the last crop of fallen lilac blossom, her tear-tired eyes beheld Lily Wang Sen prancing along the footway uttering piercing shrieks of excited joy as she roused the neighbourhood to take part in her discovery that “the little ’un next door was bein’ buried at last.”

~ Mills, E. (1905). “THE CHEE CHILD.”. The Pall Mall Magazine, may 1893-Sept.1914, 36(151), 646-649. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-periodicals/chee-child/docview/6352410/se-2

Illustrations by Arthur H. Buckland.