by Meg Brayshaw

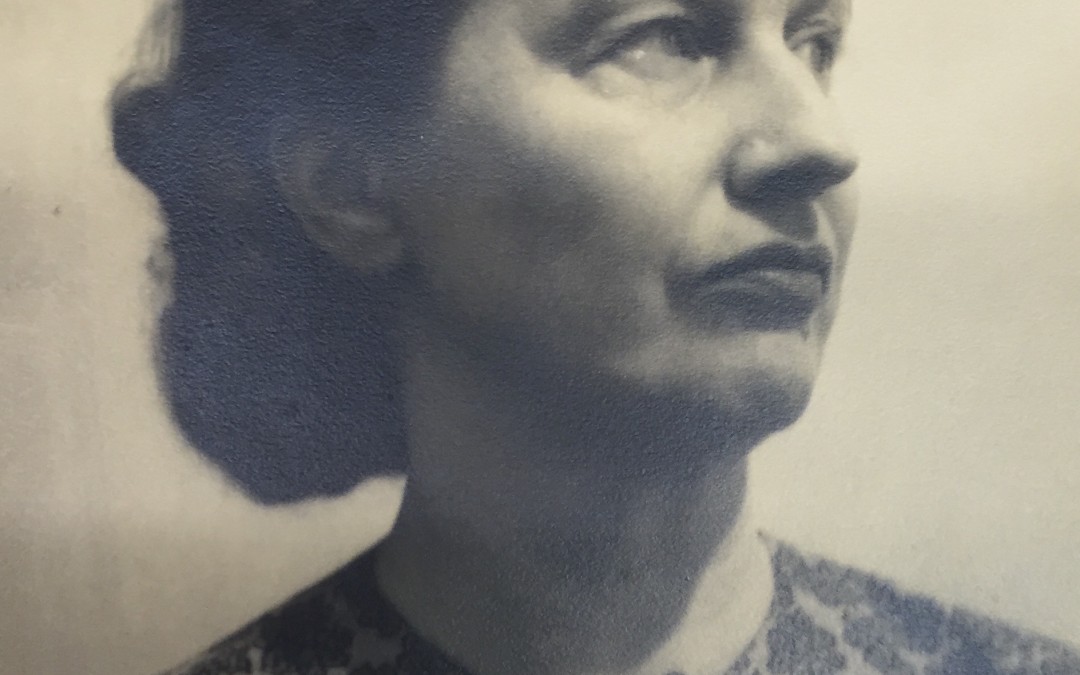

When we first published this essay by Meg Brayshaw in July 2017, she began: “Yesterday marks 115 years since the birth of the writer Christina Stead, whom critics and readers are only quite recently recognising as one of the twentieth century’s great masters of the novel form.”

When we first published this essay by Meg Brayshaw in July 2017, she began: “Yesterday marks 115 years since the birth of the writer Christina Stead, whom critics and readers are only quite recently recognising as one of the twentieth century’s great masters of the novel form.”

Born in suburban Sydney in 1902, late in life Stead claimed that a sense of place had always been impossible for her: she said she had ‘never had a home’ (Blake 2). Indeed, after leaving Australian in 1926, Stead lived in numerous countries across three continents, writing in and of them all. She returned to her home country for good in 1974, where she died in 1983.

Over a fifty-year career, Stead produced twelve novels, two collections of stories and four novellas. Their location and subject matter differed wildly: Stead wrote of street urchins in Sydney as compellingly as she did ponderous New Yorkers and confused English housewives. Stead can be difficult to pin down: she expressed great love for James Joyce and her early works especially reflect the influence of the Irish modernist. She loathed Virginia Woolf, despite some critics finding confluences between them. She coined the term ‘male chauvinist’, but like many women of her generation, she rejected the label of ‘feminist’.

When asked about her style, Stead claimed that like her father, the ichthyologist David G. Stead, she was a ‘naturalist’: her books were reflections of life, she said, nothing more and nothing less. Indeed, she regularly modelled her most despicable characters on people she knew, and was not shy about this. In her archive held at the National Library of Australia, there is a copy of her first novel, Seven Poor Men of Sydney, which she sent to her cousin Gwen with the character list annotated by details of their real-life inspirations.

Nevertheless, despite the immense variety of her oeuvre, it is difficult to mistake a Stead novel. They all feature the same focused ferocity, the same intense verbosity. Her characters speak their most uncomfortable truths, embarrassing themselves and humiliating each other. We read white-knuckled, forced to bear witness to this parade of human frailties and everyday traumas.

Stead’s reputation as a writer has faced a series of crests and troughs: as Fiona Morrison’s recent, brilliant essay in Australian Literary Studies argues, cycles of neglect and ‘rediscovery’ have defined Stead’s career almost from its beginning. In 1967, amidst growing international acclaim and after years of little recognition in her home country, Stead was nominated for the Britannia Australia Award for her contribution to Australian literature; however, the $10 000 prize was not awarded on the grounds that Stead’s many years abroad exempted her from the Australian canon.

Now, we happily claim Stead as one of our best writers, and many of her works are back in print thanks to Text Publishing and Melbourne University Press’s Miegunyah imprint. Attesting to Stead’s enduring appeal, these new editions all feature introductions by outstanding contemporary writers, critics and scholars. Delia Falconer, whose Sydney is an incredible love letter to the city, writes on Stead’s Seven Poor Men of Sydney, which details the lives of a group of young men and women who navigate with varying degrees of success the world of work and politics in the dynamic city of the interwar period (1934). David Malouf introduces the New York novel A Little Tea, a Little Chat (1948). Michelle de Kretser, whose award-winning Questions of Travel (2013) slyly references Stead’s own novel of transnational dislocation, For Love Alone (1944), provides the introduction to Cotter’s England (1966), a study of class, politics and love in post-war England.

The best-selling American novelist Jonathan Franzen introduces what many critics consider Stead’s masterpiece, the hefty family saga The Man Who Loved Children (1940). The novel’s eponymous Sam Pollitt, modelled on Stead’s father, is one of the twentieth century’s great literary monsters. Delving into tortured family dynamics and the myriad ways in which humans hurt the people they claim to love, it is a book best read, depending on one’s taste, with either a cup of chamomile tea or a stiff gin and tonic.

Stead’s other most known work is the autobiographical bildungsroman For Love Alone, which details the struggles of Teresa Hawkins to escape her suffocatingly middle-class, suburban world by saving enough to book a passage to Europe, where she is determined to find the beauty, truth and love she knows she deserves. One feels Teresa’s pain in every gnarled word, every tangled sentence. Fiona Wright responds beautifully to the novel in a 2013 essay for the Sydney Review of Books, which can be read here.

Also back in print is The Little Hotel (1973), one of Stead’s last novels, a slim book with all the delicious brevity of a one-act play. It takes place almost entirely within the claustrophobic confines of a ‘fourth-rate’ hotel by Lake Geneva in the nebulous period just after the second world war. With what Lisa Gorton calls ‘precarious brilliance’, the novel details the petty dramas of revenge and romance played out by its eccentric cast, the hotel’s long-term residents. For all its wit, the book precisely dissects life in debilitated, post-war Europe. Readers new to Stead might pick up The Little Hotel first: it is a good introduction to her style and concerns, without requiring the emotional stamina demanded by her longer, heavier works.

This is not to say that Stead is always hard-going. In the course of reading one of her novels, we are regularly rewarded for our suffering with passages of the most luminous, exquisite prose. Stead is willing to wound with her words, but she also knows how to apply them as a salve and she does so readily. Personally, Stead earns my loyalty as a reader when she achieves the nearly impossible by doing both at the same time. Take this passage from For Love Alone, in which Teresa looks into the hearts and souls of the women around her, and is sorely disappointed by what she finds:

As the burning sun bored into her and the reflections from the water dazzled her, she saw insistently, with the countless flaming eyes of her flesh, the inner life of these unfortunate women and girls, her acquaintance, a miserable mass writhing with desire and shame, grovelling before men, silent about the stew in which they boiled and bubbled, discontented, browbeaten, flouted, ridiculous and getting uglier each year. (p. 20)

Works Cited:

Blake, Ann. Christina Stead’s Politics of Place. U of WA Press, 1999.

Stead, Christina. For Love Alone. Melbourne U P, 2011.

Meg Brayshaw completed her doctorate at the Writing and Society Research Centre, Western Sydney University in 2018, and is now a full-time lecturer in Australian Literature at the University of Sydney. Her thesis focused on representations of Sydney in the interwar fiction of Australian women writers. She has had articles on the work of Christina Stead and Elizabeth Harrower published in Australian Literary Studies.