by Whispering Gums

A post in our series featuring works published in 1924 (or by authors who died in 1924). This post’s subject is a short story published in The Queenslander on 16 February 1924, by the Queensland-born writer, J.M. Stevens.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

J.M. Stevens proved a challenge to fully identify. AustLit does have some information, mainly sourced it seems from information on her sister, Maymie Ada Hamlyn-Harris. It tells us that J. M. Stevens was the daughter of Ernest James Stevens, who was Queensland state politician (MLA, then MLC, from 1878 to 1920) and Managing Director of the Brisbane Courier. Her mother, Mrs A. C. Stevens, came from a pioneering Victorian pastoral family. Stevens’ sister, Maymie Ada Hamlyn-Harris, was a writer and convenor of the Lyceum Club literary circle. Stevens married John Frederick Stevens around 1917 (meaning her last name stayed the same).

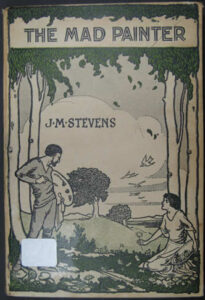

Austlit gives her dates as 1887 to 30 May 1944, and uses J.M. Stevens as their entry point for her. They add that she also wrote under other names: Joan Marguerite Stevens, Janie M. Stevens, Joan M. Stevens. The University of Melbourne’s Colonial Australian Popular Fiction digital archive. agrees with Austlit’s dates, but gives her name as Janie M. Stevens, and lists one book for her, The mad painter and other bush sketches, by J.M. Stevens.

Austlit gives her dates as 1887 to 30 May 1944, and uses J.M. Stevens as their entry point for her. They add that she also wrote under other names: Joan Marguerite Stevens, Janie M. Stevens, Joan M. Stevens. The University of Melbourne’s Colonial Australian Popular Fiction digital archive. agrees with Austlit’s dates, but gives her name as Janie M. Stevens, and lists one book for her, The mad painter and other bush sketches, by J.M. Stevens.

However, Trove unearthed a bit of a mystery. On 31 May 1944, Brisbane’s The Telegraph reported on the death of Mrs J, Stevens. It says:

Mrs Joan M. Stevens, whose death look place yesterday afternoon at her home, Bylaugh, Glenny Street, Toowong, had been an invalid for many years. She was the fifth daughter of the late Mr E. J. Stevens MLC and the late Mrs Stevens, and had lived practically the whole of her life in Brisbane and Southport. Mrs Stevens was gifted musically, showed considerable talent as a painter and like several members of her family possessed distinct literary gifts, two of her books having been accepted for publication in the south. The late Mrs Stevens, who was the wife of Mr John F. Stevens, is survived by her husband, one daughter, three sons, and one granddaughter. Mrs Stevens was the third sister in the same family to die within six months; Miss Alys Stevens died in November last in Melbourne, and her eldest sister, Miss J. M. Stevens, died in Brisbane a few weeks ago.

So, this seems like “our” J.M. Stevens – same death date, and married to Mr John F. Stevens. But, they also mention a sister, “Miss J.M. Stevens”. Three months later, on 17 August, this same newspaper announces the posthumous publication of a novel This game of murder, and says it

was written by the late Joan M. Stevens (Mrs J. F. Stevens), whose death took place a short time ago. The late Mrs Stevens, who was the fifth daughter of the late Mr E. J. Stevens, MLC, a former managing director of the “Courier,” belonged to a literary family. Her sisters included the late Miss J. M. Stevens, the writer of short stories and nature studies, whose death occurred earlier in the year. Another sister is Mrs M. Hamlyn-Harris, who has published several books of verse.

AustLit also says that J.M. Stevens (remember, aka Joan M. Stevens and Janie M. Stevens) was a freelance journalist, with articles and short stories appearing in the leading magazines and weeklies in Australia and New Zealand in the earlier part of her life. In her later years, it says, she wrote a long series of nature studies for the Sunday Mail. Further, she, like others we have written about here this year, was also a successful radio writer whose work was broadcast on Brisbane radio stations. My question is, who wrote the short story we are sharing today? Mrs Joan M Stevens or her sister Miss J.M. Stevens? And is Janie another name used for Joan, as AustLit suggests, or? Who wrote The mad painter and other bush sketches? The cover says J.M. Stevens. It sounds like a nature-related work, and Brisbane’s The Week writing about it on 7 January 1927 describes its author as “Miss Stevens … nature lover and also something a humorist”.

Then I found it! The Brisbane Courier, in an article on Queensland writers on 15 October 1927 identifies Janie Stevens as The mad painter’s author. So, I’m confident now that we have two sisters here with the initials J.M. One (Miss Janie) wrote The mad painter, and the other (Mrs Joan) wrote This game of murder. As for who wrote the rest, who knows?

Now, to this week’s story. Like my last couple of stories, “The butterfly symphony”, is a romance, but, also like them, there is an added interest, In this case it is skulduggery in the music world. This suggests that this J.M. Stevens might indeed be our “gifted pianist” Joan? Anyhow, read on… Here we are sharing the final part 3 of the story which was serialised over three weeks. Click on the links for Part 1 and Part 2.

The butterfly symphony

By J. M. Stevens

News came that the Symphony had made its debut. Segbie produced it with “gratifying success.” Why had he not let Lefroy know in time to be present? True, he might have seen the advertisement in the paper, but his new work absorbed all his time, and attention. Newspapers had been sadly neglected of late. What a fool he had been! He read a note from the publisher, enclosing a cheque, also cuttings from several newspapers, all of which spoke well of the production.

“Quite a stir has been made by the New Symphony”, said one. “A crowded house, entirely in sympathy with the music, must have been gratifying to the composer, whoever he is.” There followed a criticism of the Symphony, which showed the writer to be well up in his work. Lefroy gave a sigh of relief as he returned it to its envelope.

If only he could have been there! He was jealous of Segbie’s connection with the thing. Yet what could he do? Segbie held him in the hollow of his hand. At lunch time Oliver Forman alluded to Segbie’s success as a producer.

“I see he is to bring out another symphony,” he said. “It is to be called the ‘Butterfly Symphony,’ and is to be accompanied by a film of the new colour photography.

“Queer chap,” commented a neighbour. He was in the drapery business, and not interested in much outside his own affairs.

“Wonder what he will think of next?”

“It is all right for the general public —clever move in that direction,” said a third. “But the musical part of the audience may not care about it.”

“Segbie knows his business,” said Forman. “The general public, as you call it, matters most.”

“I don’t agree with you.” The draper smiled indulgently. “It is possible the thing will take on if it is done properly. There are certainly possibilities from an artistic point of view.” “You came down to-day,” said Lefroy to the third speaker. “Did you hear the last symphony Segbie produced?”

“By Jove, I did!” His face lit up. “It was the finest thing the Orchestra So-ciety has done. Segbie’s success is wonderful.”

“Segbie’s success?”

“Well, the thing is generally attributed to him, you know, though for some reason or other he won’t own to it just now. I asked him point-blank who wrote it, and be just smiled, and said I could draw my own conclusions.”

Under the promise of anonymity, with all that lay behind it, Lefroy did not dare allow them to suspect the true facts of the ease. At the same time he imagined the other might be misjudging Segbie’s intentions, biassed by his own friendly prejudice.

Forman and Lefroy found mutual interest in musical composition. The former, very keen where amateur theatricals were concerned—for he wrote light operetta scores — frequently visited the room used by Lefroy as a workshop. He constantly appealed to his new friend for assistance, which was freely given.

One day he required some information regarding arrangement of scores which an old manuscript of Lefroy’s would demonstrate. Being busy just then, Lefroy sent him to a drawer in his writing table to look for what he wanted.

He had quite forgotten that the old original score and rough notes of the new symphony in amongst the manuscripts. Not unnaturally, Oliver thought it might be the one he wanted.

He drew out the bundle, and, spreading the sheets on the fable, began to study them closely.

Lefroy noticed that a puzzled expression had come over his face, but even then did not realise what had happened. To any one with considerably less know-ledge of composition and original copies than Oliver Forman it would have been evident the manuscript was the writer’s own. Oliver knew Lefroy’s method of working into the bargain. He could not understand the meaning of what lay before him.

“I thought Segbie is supposed to have written the New Symphony?”

Lefroy, caught unawares, gave a startled exclamation.

“What have you got there, Forman?”

“The original score of the New Symphony but it appears to be your own.”

Thoroughly taken aback, the other gazed at him speechless for the moment. What a fool he had been to send Forman to that drawer! He had no one to blame but himself.

“There is no doubt about it,” said Oliver, a little doggedly. “You have stumbled on a fact. Only one person knows besides yourself.”

“Segbie of course. But why’?”

“I can’t tell you that.”

“It is a wicked shame!”

“There were circumstances——”

“I don’t care a hang about circumstances. I know Segbie, and if he can take unfair advantage of any one he will do it. See here, doctor, Fate’s a funny a funny thing. I came across some-one the other day whom Segbie is blackmailing too — a woman.”

“You can ‘t mean Inez Macdonald ?”

“That’s so. She is a client of mine, and an old friend. Hadn’t you better tell me the whole story? It seems to me it may be coincident with hers, and possibly I can help you both.”

It would be difficult for anyone not in similar circumstances to imagine the relief with which Lefroy poured out the tale to this youth, who inspired him with a confidence he had not felt for years.

“He has you both in a bad position.”

“Did Inez have a knife?”

Lefroy brought out the words with difficulty. He felt all the agony and worry of that awful time sweeping over him again with the bare telling of the tale.

“No.”

“Then who, in heaven’s name, could have been responsible?”

“She told me she had a companion who came to her assistance when Riley would have struck her, and that it was possible that he had had a knife unknown to her.”

“It is a most extraordinary thing.”

“I have the feeling I may be able to help you both.”

“If you only could!”

“Then give me full authority to do what I can.”

“I shall be glad to do that. But I did not know you were in the service, Oliver?”

“I’ll make a clean break of it, doctor. To tell the truth, I came here to be near you and learn what I could.”

“How did you come to connect me with the case?”

“From something Miss Macdonald let fall. Besides, I put two and two together, remembering gossip.”

“That is all over now—Inez, I mean.”

“Yes, I understand that.”

“Does your sister suspect?”

“No.”

“Knowing all you do, do you object to our friendship?” The words came slowly, painfully.

“No, I don’t, Lefroy. I’m a pretty good judge of character. But if I did it would make no difference. My sister stands for herself.”

Lefroy never forgot that day when hope once more seemed to bring promise that the intolerable burden beneath which he laboured might yet be lifted. Desiring solitude in which to think matters over in the light of this new aspect, he climbed to the summit of Big Burleigh finding mental relief in the somewhat severe physical strain.

A glorious view of sea, sky, and shore met his eyes. To the north, a long stretch of beach broken by Little Burleigh, a smaller headland than that on which he stood. To the northwest, scrubland, plain, and the hills of the Macpherson Range. Southward, first Currumbin Rocks, breaking the expanse of beach, then Tweed Heads, with Point Danger like an inky finger pointing out into the ocean.

Below lay an inferno of rocks and waves and spray. Tallebudgera Creek swept round from the southern side of the hill and joined in the conflicting currents. The water was so clear that Lefroy could see fish moving in its amber depths, and an occasional stingaree (or stinging ray), in sharp relief to the yellow sands below it.

There was a wonderful sense of freedom which unfettered Nature alone can give. Compared with the frets, and jars of ordinary existence, it held balm which spelt big things as against little things-the greater issues no longer hidden by the abnormal growth of smaller ones.

Far below him on the beach, Lefroy could see Helen Forman. It seemed a portent for good that she should also be in the picture. The great night of the second symphony drew near Lefroy had returned to town that he and Segbie might work through the music preliminary to the concert. He had not seen the Formans for some time. Oliver’s quest seemed as far from fulfilment as eyer; in fact, Lefroy had come to regard it as but a forlorn hope after all. For all that, he had not sunk back into the previous apathy of lack of interest in the future, which spoke well for the sojourn by the seaside; and the stimulus of his friendship with Helen.

The Butterfly Symphony appeared on the programme after the interval. Lefroy had reserved a seat in the front row of the gallery, a little to one side. There were many in the large audience he knew, but he saw only a mere handful of acquaintances to bow to, which—he thought spoke for itself. The unsuccessful is seldom the popular man.

Segbie as a conductor was popular. This evening, in particular, he seemed to be received with added enthusiasm. He bowed acknowledgment to continued acclamation until the entrance of the Vice-regal party, and the playing of the National Anthem created a diversion.

By the time the first part of the pro-gramme was ended, and the interval drew to a close, Lefroy felt desperately sick with nervousness. What if the thing were a failure? What if Segbie’s idea of the pictures should prove burlesque to the music-lovers, and unsatisfactory even from a spectacular point of view? Why did they not begin? Has something gone wrong? Where was Segbie? Ah, here he came again, suave, as usual, bowing his way to his seat.

The lights were lowered. Segbie waited ostentatiously until the last restless member of the audience had subsided into attention, and then raised his baton for the commencement of the Butterfly Symphony. Lefroy’s fears fled as if my [sic] magic. What a fool he had been to doubt Segbie! The thing was good in its dual parts of film and music. He sat rapt, even though it was his own composition.

First the introduction, Burleigh came back to him, the glade where the idea of the symphony had occurred the exquisite flight of butterflies against the green of the trees, the scent of the wild privet. He heard the sea in the distance, the soft sound of the wind in the trees, the hint of the approaching storm. Then began the refrain which ushered in the pictures. Upon the screen he saw the butterflies in their setting, of the little glade. The pictures blended with the music and were not self-assertive. They formed the accompaniment, not the theme itself. Segbie had seen to that. They helped to interpret the music for those who did not under-stand. They did not interfere with those whose principal interest lay in the music itself.

Then came the storm. Big Burleigh vibrated beneath the thunder of the surf on the rocks, the crash of the wind in the timber. Deep notes came from far out to sea, shriller calls from the shallows, and on the film Nature bowed beneath the weight of wind and rain. They saw the wattle and the privet, bent, broken. They saw the rivulets draining the mountain side. They saw all swept with unutterable confusion ere the first gleam of sunlight came once more across the drenched blooms.

Lefroy’s neighbour, evidently a musician, mattered excitedly during the first part. As the theme grew he subsided into, silence. The audience were completely taken by surprise, and it was evident from the very first that the thing was to be a success. Then came the end of the storm, the retrain again, but in a minor key, and only a few butterflies where previously there had been such a riot of moving colour.

There can surely be few sensations in the world such as heating the work one has toiled, upon for months presented in its entirety by an orchestra qualified to do it justice. Not till then can be known the satisfaction of success or the hideous disappointment of failure. One effect in the music sweeps into another, one movement follows another—the whole picture is complete for pictures and sound tread closely together in the world of art.

Lefroy forgot the audience. He gazed over the heads of the people to where the stars shone through the opposite window. Nervousness was a thing of the past. He did not even care what, the people thought of it, for he knew it was good.

Silence and the light again.

For a few seconds no one moved or spoke. The applause when it came was more than appreciative. It was enthusiastic. Lefroy became aware that they called for the composer, and for a frenzied moment contemplated flight, until it came upon him with a shock that it was Segbie they meant, Segbie, who bowed and smiled and accepted the acclamation complacently.

The aide from the Governor’s box approached the platform and spoke to him, and he stepped down and made his way to the beflagged enclosure, the people still applaning [sic].

“That settles it,” said the little man by Lefroy’s side. “Segbie has acknowledged he wrote the symphonies.”

A confrere in the row below acquiesced loudly. “A great man, and doesn’t he know it. I tell you he’s it!”

Lefroy never knew how he pulled himself together, and rose to leave the hall. His head ached and he felt very ill, and be longed to gain the doorway where cool night air might whip the fogs from his brain. Then his heart began to beat madly. He saw Forman on the platform – knew he spoke, but could not hear what he was saying, and the next instant his own name resounded through the building, “Lefroy! Lefroy!”

A group of enthusiasts took up the cry as in the old College days- “We want Lefroy!” They whistled, shouted, and stamped their feet on the floor. Every one laughed, and clapped and joined in the demand. The excitement was intense.

In vain he tried to slip away. A sea of faces turned towards where he stood hesitating in the gallery. He had perforce to make his way to the stage. He found himself saying as Oliver drew him up the steps of the platform. “This is madness.”

To which the other made reply, “No, it is all right, old chap. I will tell you all about it afterwards.”

There followed the ordeal of being escorted to the Governor’s box, where he was congratulated with a warmth that left no doubt as to its genuineness, while

Segbie explained that he had but taken the applause on behalf of his friend, who he did not know was in the audience, and who had previously expressed a wish to remain anonymous!

Lefroy made his escape as soon as he could conveniently do so, and was met in the doorway by the excited Oliver.

“Helen is waiting in the car. You are coming back to the hotel with us.”

“But I don’t understand! For God’s sake, Oliver, tell me what it is all about!”

“Just this: Riley was found by a foreign waiter who had a grudge against him. The man, doubting he was dead, ran a knife through his heart!”

“Am I hearing all right? It is all a dream?”

“Segbie only bluffed. He’ll see the whole thing in the morning paper. There was not time to tell you to-night before you went to the concert, so we followed you here. I guess Segbie will feel pretty sick.”

There was no time for more. Helen’s greeting almost proved the last straw that broke the back of his self-control. The sudden lifting of the burden, the new hope, held by the future, the wonderful success of his music, and the friendliness of the crowd—surely it was all a dream? They realised a little of what he felt and chatted to each other, giving him time to pull himself together.

“Take him up to our sitting-room. Helen,” adjured Oliver, “while I go and order supper.”

Once in the privacy of the Formans room Lefroy turned impulsively to the girl, “It all means nothing unless you care,” he said eagerly.

For answer she gave him both hands and lifted her face to his. He had time to wonder anew at the wonderful symphony which darkened her grey eyes before their lips met.

Sources:

J.M. Stevens, AustLit (with their source given as ‘Mrs. Hamlyn-Harris (Maymie Ada)’, A Biographical Record of Queensland Women, 1939).

J.M. Stevens, “The butterfly symphony”, The Queenslander, 2, 9 and 16 February 1924

Other sources are linked in the article.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Whispering Gums, aka Sue T, majored in English Literature, before completing her Graduate Diploma in Librarianship, but she spent the majority of her career as an audio-visual archivist. Taking early retirement, she engaged actively in Wikipedia, writing and editing articles about Australian women writers, before turning to litblogging in 2009. Australian women writers have been her main reading interest since the 1980s.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks