by Elizabeth Lhuede

Another in our series of posts on works published in 1924.

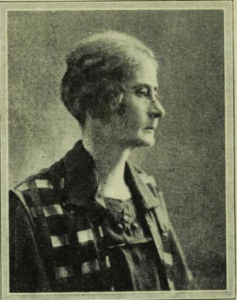

Mary Simpson, short story writer and dramatist, was born in Stalwell, in Victoria, in 1884. She began publishing in the early 1900s, and her last work, a play, appeared in 1940. In 1953, presumably after her death – I haven’t been able to find a death record, one of her short stories was selected for Colin Roderick’s anthology, Australian Round-up: Stories from 1790 to 1950. At the back of the book, a short biography of the author appears:

Mary Simpson, short story writer and dramatist, was born in Stalwell, in Victoria, in 1884. She began publishing in the early 1900s, and her last work, a play, appeared in 1940. In 1953, presumably after her death – I haven’t been able to find a death record, one of her short stories was selected for Colin Roderick’s anthology, Australian Round-up: Stories from 1790 to 1950. At the back of the book, a short biography of the author appears:

Mary Simpson – ‘Weeroona’ of the Bulletin – a native of Stawell, Victoria, who before her marriage was Mary Williams, came of English West-country stock… It was during her early days in Melbourne, after the death of her father – which left the family in parlous financial circumstances – that her sister sent one of her sketches to the Bulletin. Thereafter she contributed regularly to it and to the Woman’s Mirror… Besides stories and sketches she has written light one-act plays for amateur production.

Several of the plays mentioned were produced for the Australian Literature Society.

In 1938, M A Hunter, President of the Henry Lawson Memorial and Literary Society, compared her work favourably to that of Henry Lawson. By then, however, both Lawson and the author seemed to belong to an earlier time. Indeed, Zora Cross (1890-1964), writing as “Bernice May” in 1928, who featured Simpson’s work in The Australian Women’s Mirror, gives a sense of the author’s popularity in the early 1900s:

Travelling home from school once during my high-school days, I was annoyed with a whole railway-carriage full of people because a Bulletin was passed round and one by one those occupants read a “Weeroona” story over which they laughed and laughed while I did not. Oh, yes, I was handed the paper, though the red-faced shearer did say as he gave it to me, “You won’t be up to this yet, miss, but you can look at the pictures”. As a matter of fact I was not up to it. I could not read Bulletin prose to enjoy it till I was long past my teens. Laughing heartily over a collection of “Weeroona’s” humorous stories only yesterday, I wondered, as I wiped tears from my eyes over her sale-time yarns, what on earth had prevented me from laughing over many of her stories years and years ago. They are perfectly simple and straightforward – though always, even in the most humorous, there is something in them somewhere that gets beneath the surface.

Cross alludes to possible reasons for the author’s popularity, her writing in the tradition of Henry Lawson and her gender neutral pseudonym:

Like Henry Lawson, the only prose writer with whom she can be compared, she seldom bothers about a plot. For the most part her short stories are really sketches, and belong to the older form of Bulletin work rather than the modern, in which the plot is becoming more and more developed. “After Lawson,” I have heard readers say, “give me ‘Weeroona,’ whoever he may be.” For “Weeroona” is generally regarded as having a man’s touch.

Commenting on Simpson’s contribution to the Roderick anthology, a reviewer remarked that, among the humorous stories, it is “the most mature, the most sustainedly droll”.

Today’s feature, Simpson’s story, “The Old Place”, isn’t one of her humorous sketches. Written for the Women’s Mirror when Simpson was 40, it was evidently inspired by the long-ago sad occasion of her father’s death, and the subsequent loss of her family’s rural home. It does, however, as Cross suggests of her writing, convey both a sense of a bygone era and something about human nature that “gets beneath the surface”.

~

The Old Place by Mary Simpson (1884-1952?)

IT is the last day at the old place. The auction is over, and the buyers are lingering idly with their arms full of hens and baskets filled with home-made preserves.

Some are carrying away small articles of furniture while others are loading wagonettes with the heavier pieces. On a dray is the dining-table, upside down and packed with tin-ware, bound for a selection further out. With the table has been sold the red, ink-stained cover one sees its fringed ends flap ping in the wind.

The auctioneer, a flabby man in need of shaving, standing with one foot on a chair, is settling accounts while cracking time-honored jokes with the smiling crowd.

It has been quite a comedy altogether, an oasis of fun in the dull monotony of Iron bark, and the Ironbarkites have made the most of it. Not that they are unsympathetic— but a sale is a sale after all, and not an occasion for grief.

It is our last day. The luggage is stacked by the kitchen door, and the buggy, ours no longer but lent by its new owner, stands ready to take it and us to the station.

Up and down the stone steps, worn into hollows by our feet, strangers pass, bearing away our household gods. It seems an incomprehensible thing to see Mother’s cruet and the blue cushions borne away thus without protest.

Our more intimate neighbors are grouped about; Mrs. Shaw wagging her head in sympathy, and her daughter, Mrs. Barry, repeating over and over, “Well, well, well. So you’re going to the metropylis, Mrs. Tremayne? Ah, it’s just as well fer the children’s sake.” And Mother, looking strange and aloof in her widow’s black, echoes patiently “For the children’s sake.” But her sad eyes wander restlessly over the lost home yet again, taking in the swaying wattles and the blue, blue curve of the distant ranges. Soon her vision will be hedged about with buildings and long shabby streets in “the metropylis.”

“More charnces fer the children in the metropylis,” asserts Mrs. Barry. “They get a smartening-up there, an’ an insight into business. An’ no use you clingin’ on to th’ old place now that he” —

“No use, no use,” echoes Mother again, her thoughts on the new-made grave not far off where he was.

And then old Smithers, with his hair sticking through his hat, hurries in through the big gate with his sons and starts to yard the cows —old Crumple Horn and Spotty, Baldy and Billy the bull, with the straggly, stupid calves. Smithers has bought them all, along with the “draughts” and the pony.

There follows confusion and dust. Crumply and co. lumbering every way but the right one, their new owners sweating and chasing, cursing the calves all doubling and stampeding back toward the cow-sheds they know.

Then comes that stranger who holds the mortgage over the old place, and much talk ’twixt him and Mother.

Tommy and Joe, stiff and uncomfortable in new black suits, stand and stare at the newcomer’s son sitting high in the trap. Presently, when this dandy descends and throws a proprietorial air at the roof, Tommy falls upon him and rolls him in the stubble till his nose bleeds.

It is hateful, this leaving—even though it leads to the joys of city life. Leaving the barn, where we slithered from the topmost bag to the lower in lovely bumps, or plunged into heaps of sweet-smelling hay that pierced our scanty garments and scratched us sorely. Leaving the creek, with its leeches, its yabbies and blackfish. Leaving the echo that “cooee-ed” back at us from that underground tank wherein our faces were waveringly reflected. All these, dearly-loved yet lightly valued till now, seem to stretch out detaining fingers to hold us, now that we are leaving—the old place.

Inside the house a farewell cup of tea is being drunk and the sweet, sickly smell of Madeira cakes wafts out.

Mother, surrounded by neighbors, friendly yet curious, is dabbing at her eyes and fighting against hysteria. No wonder! This has been home since she came to it, a bride. Now, in the cemetery is father’s new-made grave and she is leaving him.

Time enough, with the new owner chaffering over his rights and privileges, to have one more swing—one last, never-to-be forgotten swing. So away across the paddocks the children fly, the stubble flattening and crackling beneath their boots—so different to the barefooted crossings of yesterday And the swing, buoyant, a thing of magic, controlled by the supple limbs of the girls, rises high, higher, till it seems as though their flying figures must complete the circle and go right over the top. Valkyries riding the wind—glorious, exhilarating swinging! To know the swift, upward lift, the downward drive, to feel one’s hair driven back from flushed cheeks—the delicious fear when our feet slip, the sense of power on struggling back to safety.

And then Freckles, the first-born, almost man-size in his first long pants, lurking in the busy shed trying to look indifferent.

Freckles is not coming to the metropolis. He is in pawn to the local store. He is to “work off” the account there. All is settled and agreed. Grimes has magnanimously accepted payment in service instead of cash.

And is Freckles willing? He was, it is said among the neighbors, until this last day, when he was to see the others off to the city. “Natural-like,” says Mrs. Barry in the wrinkled ear of Mrs. Shaw, “he wants to see the sights.”

But Mother knows better. Mother knows how her boy’s heart is breaking under the stiff, white shirt-not for the city sights, but because of the parting. She knows the loneliness and longing that will be his portion while “working off the account.”

Let others say, Grimes among the number, that “it will make a man of him.” Why should he be made a man of? Mother fiercely wants to know. Why should Freckles be made a man of when, despite long pants and a strap tie, he is only a boy and, to her, a baby still.

It seems as if, come to the pinch, she would sooner die than leave him. Yet there is the unpaid account.

“Such a pity their father speckeylated in the mines,” remarks Mrs. Shaw of the wagging head to the company in general. “See what’s come of it, her a widdy-woman an’ the childer faytherless!”

“Yes, yes,” agree the others; “but its best for her to go—more chances in the city, more jobs for the young uns, an if this ’ere Freckles gets an insight inta th’ grocery at Grimes’s—well, it’ll be a help to his mother later on, an’ a good arrangement.”

And so it seems to them, not being called to sacrifice.

And out of sight, Mother and Freckles are parting. Freckles is “to be a good boy” (as though he had ever been a bad one!). He is to be brave, as Mother herself is and at this she breaks down altogether and sobs in Freckles’s clumsy, boyish embrace, his tears mingling with her own.

And then the unexpected—the wonderful blaze of light that illumines that last dark day. The appearance of Grimes himself, with his nose unwiped, a chew of tobacco in his jaws, handing Mother the account with “Paid in Full! Scrawled across its total. Grimes, miser and usurer but with a streak of humanity somewhere still for the widow and fatherless: Grimes backing grumpily away from gratitude, but with moisture in his eye; Grimes who, this day has placed a hand of healing on a woman’s breaking heart.

And Freckles, the reprieved, lapsing from incipient manhood into boyhood again, is turning somersaults of joy in the dust.

The neighbors, moving in slow processional gait, gather near. Horny hands are shaken; cheery words spoken. Mother is asked to send reports on our progress as town-folk. Someone is to send us wattle in the Spring; someone else a “settin’ of aigs [eggs].”

And presently a strange solemnity falls upon us. Freckles, always a lightning change artist, becoming momentarily a man in real earnest, takes Mother arm. Silently we all press closer, each resolved not to cry and just as certainly beginning to whimper—and so we turn our backs on the old place and take our first steps to the city.

[THE END.]

References

– Andrewartha, Kathy and Leigh Hay, A Lawson Legacy: A Brief Chronological History of the Henry Lawson Memorial and Literary Society (1923-2023).

– Image source: The Australian Women’s Mirror 17 April 1928: 10.

– May, Bernice, “Weeroona”, The Australian Women’s Mirror, 17 April 1928: 10, 54.

– “Melbourne Chatter”, The Bulletin, 10 Sep 1925: 27.

– Review of Australian Round-up, The Age, 19 Sep 1953: 15.

– Roderick, Colin (ed), Australian Round-up: Stories from 1790 to 1950 (Sydney, Halstead Press 1953). No birth year given for Mary. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c8/Australian_Roundup_%28IA_in.ernet.dli.2015.182586%29.pdf p370, accessed 21/05/2024

– Simpson, Mary, “The Old Place”, The Australian Women’s Mirror, 23 Dec 1924: 9, 56.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks