October is set to be an exciting month for the Australian Women Writers Challenge! We’re holding a spotlight on Australian women writers of diverse heritage, with guest posts from Tseen Khoo, Alice Pung, Malla Nunn and Merlinda Bobis, as well as book giveaways. All those who read and review a book by an Australian woman writer of diverse heritage will go in a draw for Alice Pung’s first book Unpolished Gem (kindly donated by Black Inc) and Ruth Park’s Swords and Crowns and Rings (kindly donated by Text Publishing). This novel has been re-issued in Text’s wonderful Classics range, and Alice has written an admirable introduction to the work. The books which are reviewed will be added to our Bookshelf at GoodReads, which readers can access for more suggestions.

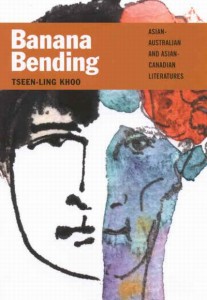

Today I’d like to introduce Tseen Khoo. Tseen wears many hats, and one of them is researcher and writer on Asian-Australian literature. In 2003 she published Banana Bending: Asian-Australian and Asian-Canadian Literatures, which she refers to below. Tseen is also a founding editorial advisor for Peril, an Asian-Australian magazine of arts and culture. In her post, Tseen voices her frustrations with the limited readings of books by Asian Australian writers, but she also signals that such readings are starting to shift due to writing by Australian women writers of diverse heritage.

Today I’d like to introduce Tseen Khoo. Tseen wears many hats, and one of them is researcher and writer on Asian-Australian literature. In 2003 she published Banana Bending: Asian-Australian and Asian-Canadian Literatures, which she refers to below. Tseen is also a founding editorial advisor for Peril, an Asian-Australian magazine of arts and culture. In her post, Tseen voices her frustrations with the limited readings of books by Asian Australian writers, but she also signals that such readings are starting to shift due to writing by Australian women writers of diverse heritage.

If you’d like recommendations on books by Australian women writers such as these, Tseen’s list is a great place to start. Happy reading and reviewing!

Diverse challenges in reading Asian Australian women’s writing

When I sat down to write this post for the AWW 2013 October focus on diversity and Australian women’s writing, I realised I’d spent too many years of my life as an academic. I had a decade or so’s focus on examining stories in terms of representational politics, talking with Asian Australian writers, and criticising notions of ‘literary value’, floating around in my head.

While this is all well and good to inform my take on diversity in writing, it wasn’t quite what I wanted to write about.

For this blogpost, I’ve focused on what spurred me to study the area in the first place. To stick at it for about fifteen years, it must’ve been quite a driver, right?

Let me tell you what it was in one word: frustration.

It all started with Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. Published in 1991, it became a global sensation and has sold over 13 million copies worldwide. The auto/biographical story of three generations of mainland Chinese women, it seemed to spark a hunger for exotic tales of oppression. These usually feature a heroine’s triumph over an authoritarian regime and/or cultural patriarchy, and an escape to a golden future in a Western nation (usually America).

It all started with Jung Chang’s Wild Swans. Published in 1991, it became a global sensation and has sold over 13 million copies worldwide. The auto/biographical story of three generations of mainland Chinese women, it seemed to spark a hunger for exotic tales of oppression. These usually feature a heroine’s triumph over an authoritarian regime and/or cultural patriarchy, and an escape to a golden future in a Western nation (usually America).

Coupled with Chang’s book success was the emergence of Chinese American writer Amy Tan’s work. Tan’s second novel Kitchen God’s Wife was published in 1991, and her first book, the influential Joy Luck Club, was published in 1989.

Coupled with Chang’s book success was the emergence of Chinese American writer Amy Tan’s work. Tan’s second novel Kitchen God’s Wife was published in 1991, and her first book, the influential Joy Luck Club, was published in 1989.

I inhaled all these books. I read Chang’s book – all 720 pages of it – in one weekend over a set of Christmas holidays; I forgot to have several meals.

Over the next few years, I noticed the number of books appearing with very similar themes, characters, even book covers. Neela Banerjee, in Hyphen magazine, even talks about the “chinking up” of Asian American book covers in her discussion about the limited representations for Asian authors.

Similarly, I started reading more reviews that irritated me because they demanded measures of ‘authenticity’ and exotic detail from the text as part of their valuation. Sometimes, it felt as if, if it’s a book by an Asian woman and she doesn’t talk about Asian women’s oppression (particularly her own), what’s with that?

For part of my book (Banana Bending), I examined the critical reception of Hsu Ming Teo’s first novel, Love and Vertigo. Many Asian women’s texts are compared to those of Jung Chang and Amy Tan (doesn’t seem to matter whether they’re fiction or biography). Teo is no exception and reviewers, although in the main positive, also performed limited readings of her novel within the tried and true categories for ethnic writing: personalised migrant tales and cultural confessionals. Even as they are doing this, many reviewers repeat Teo’s clarification that Love and Vertigo is not autobiography.

For part of my book (Banana Bending), I examined the critical reception of Hsu Ming Teo’s first novel, Love and Vertigo. Many Asian women’s texts are compared to those of Jung Chang and Amy Tan (doesn’t seem to matter whether they’re fiction or biography). Teo is no exception and reviewers, although in the main positive, also performed limited readings of her novel within the tried and true categories for ethnic writing: personalised migrant tales and cultural confessionals. Even as they are doing this, many reviewers repeat Teo’s clarification that Love and Vertigo is not autobiography.

There were two reviews that stood out for their transparent desire for a particular kind of text from Teo. One complained that “the first half of the novel is such a delight that it comes as a disappointment when the family migrates to Australia”. His review points out the mundane and colourless nature of the narrative once the family are in Australia, and implies that there are ‘enough’ of these migrant tales already. The other review has a similar protest, saying that “it is a pity that [the narrator] sounds more like an articulate authorial voice and not a hesitant young immigrant with a smattering of ‘Singlish’ patois”.

I cite these two reviews in detail because they have stayed with me all these years, and their hunger for the exotic and ‘authentic Asian’ (replete with stereotypes) is so bluntly communicated. I was taken aback that these critiques, appearing in major Australian literary pages, were so unsophisticated and essentialist.

Teo has stated that she is actively rewriting the exotic, and flags class as of more critical concern than race or ethnicity, identifying herself as a “middle-class woman” rather than Chinese or Asian. Through most of the reviews and other write-ups, much mention is made of Teo’s youth, intelligence (she has a doctorate in history) and attractiveness. Alongside the expectation for sensational colourful tales from an Asian Australian author, the reviewers’ reaction to the less exciting setting of suburban Burwood in Melbourne, Australia, indicates an impatience with the familiar, and an easy dismissal of migrant narratives as having ‘been done’.

Teo has stated that she is actively rewriting the exotic, and flags class as of more critical concern than race or ethnicity, identifying herself as a “middle-class woman” rather than Chinese or Asian. Through most of the reviews and other write-ups, much mention is made of Teo’s youth, intelligence (she has a doctorate in history) and attractiveness. Alongside the expectation for sensational colourful tales from an Asian Australian author, the reviewers’ reaction to the less exciting setting of suburban Burwood in Melbourne, Australia, indicates an impatience with the familiar, and an easy dismissal of migrant narratives as having ‘been done’.

This example presents the core of my frustration with the ways that Asian Australian women’s writing was read, and led me to a Masters, PhD, and postdoctoral fellowship that all engaged with diasporic Asian writing, and Asian Australian writing in particular.

Since I started my Masters, some perceptions and receptions have changed. The profile of Asian Australian women authors and their work has been boosted by the success of Alice Pung’s books (Unpolished Gem, Her Father’s Daughter, and the ground-breaking anthology, Growing up Asian in Australia); Lily Chan’s 2013 win of the Dobbie Award for Toyo; more consistent publication by emerging writers within creative cultural outlets like Peril (Asian Australian magazine of arts and culture); and a less tangible, but important, shift to a readership that is more increasingly informed about Australia’s diverse voices, and actively seek them out.

Since I started my Masters, some perceptions and receptions have changed. The profile of Asian Australian women authors and their work has been boosted by the success of Alice Pung’s books (Unpolished Gem, Her Father’s Daughter, and the ground-breaking anthology, Growing up Asian in Australia); Lily Chan’s 2013 win of the Dobbie Award for Toyo; more consistent publication by emerging writers within creative cultural outlets like Peril (Asian Australian magazine of arts and culture); and a less tangible, but important, shift to a readership that is more increasingly informed about Australia’s diverse voices, and actively seek them out.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks