by Jonathan Shaw

Jonathan is a retired editor who blogs at Me Fail? I Fly!. We plan for him to be a regular guest contributor with a particular interest in poetry. Here he introduces us to the marvellous Sydney bohemian writer Zora Cross (1890-1964).

Jonathan is a retired editor who blogs at Me Fail? I Fly!. We plan for him to be a regular guest contributor with a particular interest in poetry. Here he introduces us to the marvellous Sydney bohemian writer Zora Cross (1890-1964).

In the 1980s poets Judith Wright and Rosemary Dobson were approached by the Australian Jockey Club, who wanted to name a horserace after one of them. They recoiled from the notion and suggested Zora Cross, who had then been dead for nearly two decades. Judith Wright wrote to a friend, ‘It’s lucky Zora Cross can’t object, and since nobody remembers the poor woman, the good name of Poetry can’t be involved.’ That poor woman, who was phenomenally successful with readers and critics when she was in her 20s, has recently been making a partial return from oblivion.

Zora Cross had a remarkably productive writing life, and was part of Sydney’s bohemian literary scene between the two world wars. Apart from journalism and editing work, she produced five poetry books (one of them for children), six novels (two as serials in the Sydney Morning Herald), a book of essays on Australian literature, and a number of plays. Many of her poems appeared in newspapers and have never been collected, and she spent her last years working on an ambitious series of novels set in ancient Rome that were never published.

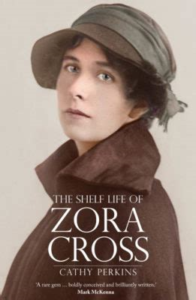

I first met her poetry when I was an editor on The School Magazine. We regularly received phone calls from elderly people asking us to help retrieve a half-remembered poem. Zora Cross’s ‘Memory‘ was often the one they were after. It was published in the magazine seven times between 1918 and 1960. It’s not her only poem the magazine published, but it is evidently the most memorable. In the 1953 City of Sydney Eisteddfod, a record 127 children entered to read it (and 107 to read ‘Dream Travel‘, another of Cross’s poems). In the prologue to her biography of Cross, Cathy Perkins writes that when she asked people if they had heard of her, some remembered reciting ‘Memory’ at school, especially perhaps the final couplet:

And Eight must never see Twenty-three

As she peeps through the door of Memory.

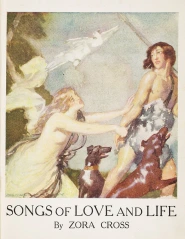

For this essay, I read mainly Cathy Perkins’s biography, The Shelf Life of Zora Cross , and Cross’s most successful book of poems, Songs of Love and Life (1917). I recommend both books.

The Shelf Life of Zora Cross tells its subject’s story as reflected in the papers of ten people, including Ethel Turner, author of Seven Little Australians; Norman Lindsay, who reluctantly accepted a commission to provide a cover for Songs of Love and Life; Cross’s publisher, George Robertson; her younger brother Jack, who died in Europe during World War One; and David McKee Wright, the love of her life, who was for a time editor of the Bulletin‘s famous Red Page, .

Zora Cross was born in 1890 at Eagle Farm, which was then a rural locality outside Brisbane, and moved to Sydney when she was 15. One of the great pleasures of Cathy Perkins’s biography is the detailed account of Zora’s writing apprenticeship before and after that move as a contributor to the Children’s Corner of the Australian Town and Country Journal, edited by Ethel Turner. Turner encouraged the young writer, and remained a friend and mentor after she outgrew the Corner and began writing what Turner called ‘heady stuff’.

Perkins gives a lively account of Cross’s early adult years performing with a theatrical troupe in North Queensland and then in Sydney, working as an editor, teaching in schools around what we now know as Sydney’s Inner West, and collecting rejections from newspapers and literary journals, with an occasional acceptance. We read of her somewhat mysterious marriage to a fellow actor, who disappeared from her life, never having lived with her, but leaving her with a son. (Perkins has unearthed the husband’s story, as Zora never managed to do: he moved to the USA in 1911, the year they married, and lived there until his death in 1967.) Zora was a striking presence in her 20s:

One day in 1915, Zora is rushing from a rehearsal at the Tivoli Theatre in central Brisbane to the office of the Bohemian to pick up her editor’s salary when she meets a journalist who will later write a profile on her for the Australian Woman’s Mirror. She is ‘slight and pale and terrific with energy’ and covered in red printer’s ink from the paper’s scarlet masthead, which looks like blood on her white dress. (page 45)

Perkins quotes copiously from Cross’s effusive and often hilarious correspondence with George Robertson and other publishers, and gives a moving account of her relationship with David McKee Wright, with whom she had two daughters and lived in relative poverty in the Blue Mountains. In the final chapters, after David’s death, she lived precariously as a single mother earning a little from journalism but relying on a pension from the Commonwealth Literary Fund. She was part of the local community, celebrated as ‘a well-known authoress’, and died of a heart attack in her garden in 1964, leaving among her papers the manuscript of her Roman novels, now reduced by time, insects and possibly fire to a condition Perkins describes as ‘more like sculpture than text’.

The ‘heady stuff’ that Ethel Turner referred to was mainly three books of poetry: Songs of Love and Life (1917), The Lilt of Life (1918) and Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy (1921).

Songs of Love and Life, whose manuscript had been rejected unread by publisher George Robertson, first appeared in a small cheap edition in October 1917. Robertson deigned to read a poem or two in his advance copy, and published a second edition a month later with a cover by Norman Lindsay. The book was a huge success.

Its popularity was mainly due to a 60-poem sequence, ‘Love Sonnets’, whose exuberant expressions of female desire – unprecedented in Australian literature – struck a chord with young men and women separated by World War One, and gave voice to changing cultural expectations about sex and romance. Despite much rhapsodising about jewels and fabrics, gods and souls, these poems still speak to us. John Kinsella included two of them (and two from The Lilt of Life) in The Penguin Anthology of Australian Poetry (2009), including number XV:

XV

Love, you have brought to me my perfect soul.

More sweet than earthly things, more precious rare,

Hiding its fragrance in my loosened hair

And folding up my body like a scroll.

O, lie with me all night, and let the roll

Of Rapture’s waves wash over us, as, bare

Of anything save Love, we haply share

The joys of our first parents’ chaste control.

My Love, my piece of Heaven God has spilled

Upon my outstretched hands, O, kiss me yet.

Here, lying close to you, I feel – I know,

My being, even now, is charged and filled

With light and bliss it never will forget

Though aeons over my cold corpse should flow.

It’s not hard to imagine a young man in the trenches or the young woman he has left behind finding comfort in these lines.

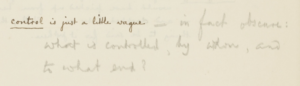

If you stumbled on the word ‘control’ at the end of the octave, you’re not alone.

That’s an annotation in the scanned copy of the first edition that I read (available from the State Library of New South Wales, at this link). In case you can’t read the image, the note says:

control is just a little vague [then, in pencil] – in fact obscure: what is controlled, by whom, and to what end?

I was reading a scan of a copy that had been annotated by the distinguished scholar-poet Christopher Brennan! He is completely, hilariously, and to my mind correctly dismissive of some of the poems, but mostly he comments as a minutely attentive mentor (something the young Zora Cross ignored, and perhaps just as well, because if she had aimed for the kind of precision he advocated, her poetry may well have lost some of its spontaneous feel).

In the case of ‘control’, I beg to differ from the great man’s implication that there’s something wrong. For me it’s like a bit of thought-provoking grit. After celebrating the rapture of lying naked in each other’s arms the poem invokes the Bible story Eden. The orgasmic waves washing over the lovers are like the ones experienced before the Fall, fully sexual and at the same time completely innocent. ‘Control’ in this context is a rough opposite to ‘abandon’. Typically of Cross’s love poems, this one is uninhibited in its sensuality and filled with imagery that comes as close to sexually explicit as the times allowed (‘my being even now is charged and filled’), and at the same time insistent on the rightness and goodness of sexual desire. Norman Lindsay’s cover may have helped sales, but female sexuality as affirmed by Zora Cross bears little resemblance to Lindsay’s pseudo-pagan rompiness.

A second book of verse, The Lilt of Life, appeared a year later, including a series, ‘Sonnets of Motherhood’, that was just as erotically charged. This is the start of Sonnet XIII:

Accept my body, Dearest, as a gift,

A precious casket of the purest pearl.

Some of her long poems in these books are pretty much unreadable. For example, ‘Man and Woman’, a 65-page essay in blank verse, a rich historical-philosophical-mystical-religious vision of the meaning of life for Woman with a strong anti-war theme, is in a poetical mode that hasn’t aged well, and was too much for my limited patience. Here’s a tiny taste, in which the poem’s speaker addresses the Christ child:

Men war. Men war for ever, but You come

Because a mother-heart is left to love.

Rachel is weeping still and Hecuba;

A thousand wives a Hector mourn again

As Aphrodite and Athene strive

Through the bruised souls of men and women too.

But, You are safe, O little child of Love,

That ages touch not with their misery.

The third book, published in 1921, communicates anti-war sentiments much more powerfully. Rooted in Cross’s own deeply-felt loss, it comprises a single long poem, ‘Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy‘, written for her younger brother Jack who had died in uniform during the war:

I only know you, brother of my blood,

Have gone; and many a friend,

Trampled and broken in the Flanders mud,

Found Youth’s most bitter end.

God! You are not yet one with the kind dust

Before new war-horns blow

And sleek-limbed statesmen in their halls break trust

To tell of other woe.

When she died 43 years later, even though she had continued to write and take part in literary life in the intervening decades, including for example a series of article in the Melbourne Herald in 1935, ‘Women Who Have Helped to Build Australia’, it was the early works that were celebrated in her obituaries. As far as I know, there is no Collected Poems, or even a Selected. Her journalism can only be found in its place of original publication, and her novels haven’t been reissued (perhaps a shame in the case of This Hectic Age, aka The Night Side of Sydney, a novel of sex and violence in wartime Sydney).

If you want to dip into her poetry a little further, you can find selections online at, for example, Poemhunter, Best Poems Encyclopedia, AllPoetry.com, Poetry.com and Old Queensland Poetry

Bibliography

Cathy Perkins, The Shelf Life of Zora Cross, Monash University Publishing, Melbourne, 2020

Zora Cross, Songs of Love and Life, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1917

Zora Cross, The Lilt of Life, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1918

Zora Cross, Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1921

Jonathan Shaw is another old white guy, with an ancient degree in Eng Lit. He’s the former editor of a children’s literary magazine who blogs about his joy in reading literature mainly written for adults.

Thanks Jonathan. A fascinating glimpse into Cross’s life and work, and into your own research life. How wonderful to discover Brennan’s notations!

Thank you, Johnathon, for your insights into Zora Cross’s life and poetry. Your mention of ‘Elegy on an Australian Schoolboy’ reminded me that Professor Peter Stanley references this poem in his WWI book ‘The Crying Years’ (NLA Publishing, 2017). The book’s title is borrowed from an expression Stanley attributes to Cross.

It was sheer luck that I read the version with his annotations, Elizabeth. At first I was just annoyed and then I recognised them from Cathy Perkins’s description. I could have spent a whole blog post on his notes – a real maser class.

Fascinating! I’m scheduling an extract including Cross’s description of meeting Ethel Turner – a bookend to your piece – for Friday. I was thrilled to discover when compiling the archives she’d been active in promoting other women writers. So many of the women she wrote about are new to me.

Thanks, Tessa. It’s interesting that her poetry still gives voice to the feel of her times.

My father was quite senior in the Victorian Education Dept. I looked in the school Readers and in his own anthology of WWI poetry, but sadly, no Zora Cross. Perhaps she was too anti-war.

It wasn’t the anti-war poems that made it into the NSW School Magazine, Bill. That would have been worth writing home about!

The only “Zora” I “know” is Zora Neale Hurston, so it was a treat to have another Zora to sit with her at that table in my reader’s mind. I also love the expression on that photo which graces the cover of her biography. But most of all I love the scanned annotation which gives some insight to the last word in that verse. Fascinating.

Thanks for commenting, BuriedInPrint. You may be interested in Zora Cross’s poem ‘Books’, which begins, ‘Oh bury me in books when I am dead’. It’s at xxx

Sorry, that link got muddled somehow. the correct one is https://www.poetry.com/poem/42580/books

Sorry I didn’t reply earlier Jonathan, but last week was a big one for me. I have this biography but have not yet had time to read it. My TBR is starting to overwhelm. I have now gathered together the literary biographies into one pile – though how that will help I don’t know!

Anyhow, your post made me feel that this biography will be a great read even thought I’ve read almost nothing of Zora Cross’s work (though I have come across her a few times in my Trove searches.) Also, as I was reading your post I was thinking about your comments on her “exuberant expressions of female desire – unprecedented in Australian literature” and how this “gave voice to changing cultural expectations about sex and romance”. It made me think that poetry has often led the way when it comes to expessing sex, love and passion, perhaps because, to some degree, the detail can hide a little behind poetic imagery?

I had heard about Zora. Cross as among my mother’ possessions I found an old battered copy of Poems of Love and Life! She had written on the piece of brown paper wrapped around it that it was my grandfather’s favourite book of poetry. He died in in 1952 aged 78 so obviously loved her poetry when a young man. It is so good to read about Zora Cross and I will read the book of poems. Is it worth preserving the old book or sending it to somewhere to be preserved? And where do I find her biography?