by Bill Holloway Not the first novel of Australian convict life, that was Quintus Serviton (1831), but a vivid, and the earliest, picture of female convicts in domestic service.

Not the first novel of Australian convict life, that was Quintus Serviton (1831), but a vivid, and the earliest, picture of female convicts in domestic service.

From her home in Exeter, Caroline Leakey (1827-1881) at age 20 “sailed to the British colony of Van Diemen’s Land, to join her sister Eliza, who had migrated to Hobart Town several years earlier with her clergyman husband, Reverend James Medland. Shortly after her arrival, her health deteriorated and she was bedridden for much of the remainder of her time in the colony. In 1851, she lived for twelve months at the convict settlement of Port Arthur. When she returned to Hobart, she fell ill again and her family urged her to return to England, which she did in March 1853.” (Wiki)

The Broad Arrow (1859), which she published under the pseudonym Oliné Keese, was her only novel, though she also had some poetry published, including Lyra Australis, or Attempts to Sing in a Strange Land (1853) which seems to have been published under her own name (Trove). Wikipedia says The Broad Arrow was re-issued in heavily abridged form in 1886, and that was not rectified until Jenna Mead restored and published the original text in 2019. The version I have read for this review, which I assume is the pre-1886 original, was from Project Gutenberg.

The novel’s subtitle is “being passages from the history of Maida Gwynnham, a lifer“. Maida is a young woman of gentle birth and strong character, who on being sent away at 16 by her father to a school for young ladies, falls for the charms of a young, unscrupulous officer, Norwell; bears him a child; is abandoned; and feeling unable to return home, lives in poverty for three years, until, the child dying, Norwell seeks her out and tricks her into altering and countersigning a cheque on his uncle, using the name ‘Martha Grylls’.

Just as she is burying her baby in the woods, constables appear to arrest her. Under the name Martha Grylls, she is charged with and convicted of murdering her son and the lesser charge of counterfeiting is allowed to slide, so Norwell is protected. Matha’s sentence of death by hanging is commuted to transportation to Van Dieman’s Land for life.

In a parallel (and soon converged) storyline, the Rev Herbert Evelyn returns from Hobart with his fragile and motherless daughter, Emmeline. Evelyn speaks to ‘Martha’ in gaol and forms a good impression of her. The English climate does not agree with Emmeline and the Evelyns return to Hobart taking with them Emmeline’s lively cousin Bridget, where they live with Herbert’s lawyer brother George, George’s wife, and young son, Charlie.

Mrs Evelyn is high-handed in her treatment of convict servants and gets through them pretty quickly. Soon, the Rev Herbert is able to persuade his brother to ask for Martha to work for Mrs Evelyn as cook/housemaid. Martha, who at this point reverts to Maida, strikes Mrs Evelyn as having too high an opinion of herself, and much of the rest of the novel is to do with them striking sparks off each other, and of Maida copping increasingly severe punishments as her stiff neck turns small infractions into larger ones.

The saving graces of the household, for Maida, are the reluctant tolerance of Mr Evelyn, the friendship of the Rev Evelyn, and her love for the gentle invalid Emmeline.

Leakey is highly critical of the arbitrary way both judgement and punishment were administered in the colony. Mr Evelyn has resigned his positions (and £500/year salary) as magistrate and member of the Executive, out of disgust

But with his public life Mr. Evelyn did not abandon a career of usefulness. Disgusted with the errors of judicial administration, and deploring a system which could never be reformatory until reformation commenced with itself he prepared himself to do what it would be well if every reflecting man would do when disappointed in the performance of acts of public benevolence, namely, to try how most effectually he could serve the little circle drawn immediately around himself.

Sadly, the more lenient he was with his own convict servants, the more he was taken advantage of, though he does eventually have some successes.

Guards, male and female, and hospital nurses, all of them ex-convicts, are mostly violent and corrupt. One nurse, seemingly a madwoman on the ship out, was Maida’s sworn enemy, and was sometimes, as the system wore Maida down, in a position to do her harm.

The one aspect of Leakey’s writing which is hard to bear, today anyway, is her preaching. I know this is a common feature of early and mid nineteenth century fiction, and is probably understandable that some novels read like sermons when you think that heroines in earlier fiction would pull down from the library shelves books of sermons for their edification and entertainment.

The point of the book is that Emmeline is dying and that when she dies she should not be mourned, she will have gone to a better place. Maida, on the other hand must find a way to deny her pride if she is to achieve anything approaching Emmeline’s example.

I won’t tell you how that goes, but along the way we are treated to a close observation of convict servant life; the absolute authority of the householders to whom they are assigned; and the rules and curfews which constrict their lives, with the everpresent threat of return to gaol, and consequent added punishments; and for recidivists, and as Leakey shows, for those too weak or otherwise unable to conform, the prospect of chain gangs and hard labour at Port Arthur, and for the worst of the worst, Norfolk Island.

Bridget finds it disconcerting, living in a society so dependent on convict labour

Well, then, what I mean is this: I did not expect that prisoners would so mix with us as they do in every-day life, making us afraid to look or speak lest we should hurt their feelings or get them punished. I knew there would be hundreds of convicts, but thought they would be such dreadful creatures we should only be shocked at them; and I thought there would be dreadful affrays with them sometimes; but I never dreamt of such trumpery annoyances coming out of the commonest sayings and doings, making one uncomfortable in such curious ways.

She notices too, that there are no Aboriginal people on the streets (the Black Wars had been fought 20 years earlier)

‘Uncle, what has become of all the aborigines? I haven’t seen one of them ever since I have been here.’

‘They are confined in Oyster Cove, and supported by Government; the all consists of but twenty-three; poor things! it is sad to behold them. They bequeath us a legacy for which we shall have to answer when God makes inquisition for blood. “Whoso sheddeth man’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed,” is a denunciation as true of nations as of individuals; and to them who mark these things, retribution is clearly discernible in national records.

Thoughtful readers of Tasmanian history must tremble to think how and where the retributive stroke shall fall on England or her dependencies. When they read of barbarities disgraceful to a Christian people; of murdered women; of tortured children, they can only turn and pray the anticipating prayer: “Lord, in judgment remember mercy, and visit not these sins on the head of innocence.”‘

Finally, those of you who live in or know Hobart (and I do not) should find great joy in Leakey’s detailed descriptions of life and scenery there, and in Port Arthur, apparently a ‘resort’ overlooking the famous prison.

.

Caroline Leakey

The Broad Arrow, being passages from the history of Maida Gwynnham, a lifer

first pub. 1859

Project Gutenberg version (here)

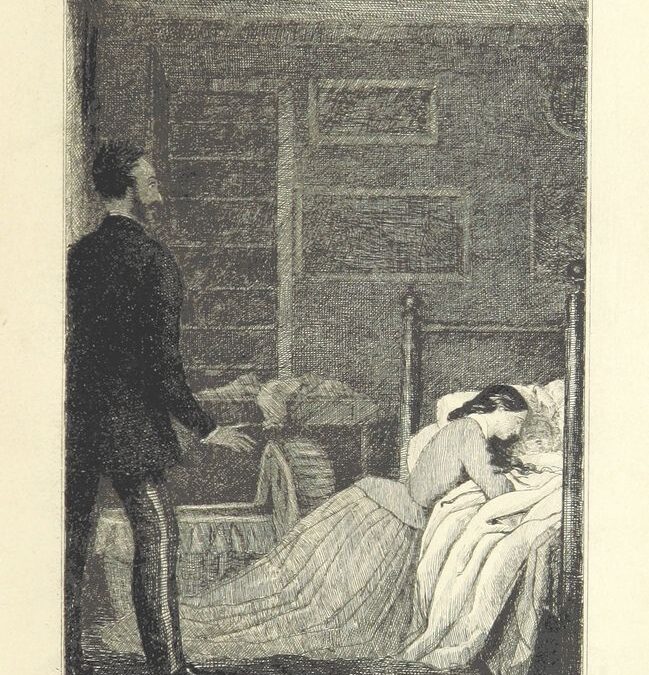

Illustration: British Library digitized image from p.67 (showing the death of Maida’s son).

Bill Holloway, the author of this review, blogs at The Australian Legend. He is an old white guy the subject of whose (very) mature age M.Litt thesis was ‘The Independent Woman in Australian Literature’.

Fascinating, Bill. Thank you.

Thanks Elizabeth, as always it is impossible to imagine why we buried our original literature for so long. A lot of it is good and all of it is interesting, at least as history.

Sorry too I didn’t stop work long enough to contribute an introduction to your extract (I’d better go and look at it)