by Bill Holloway

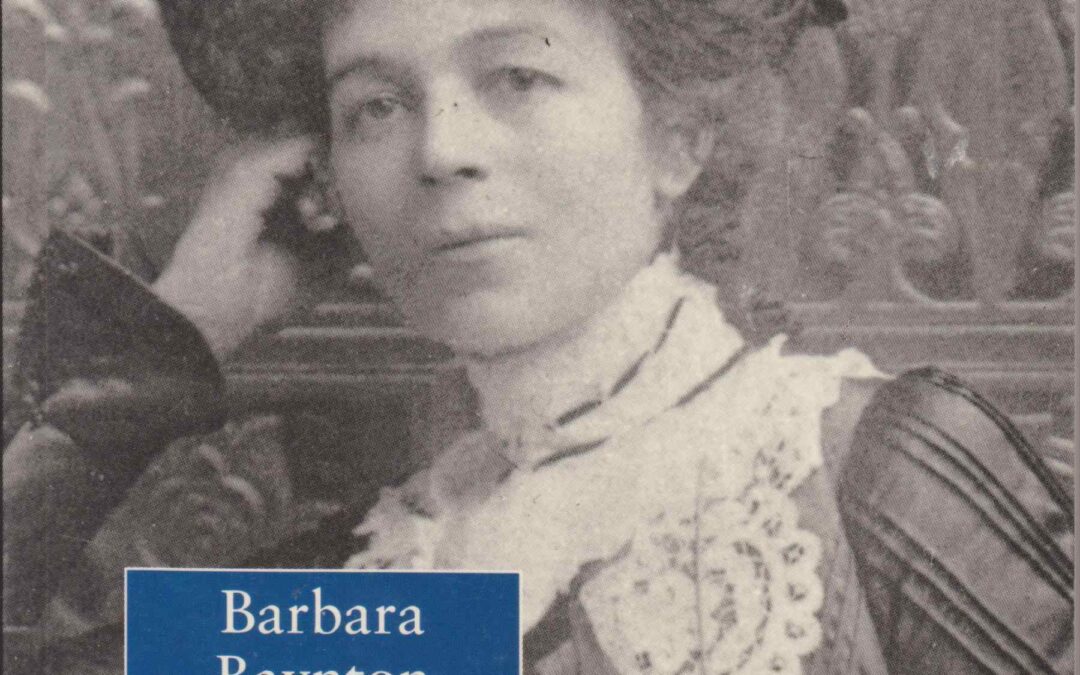

Not having a ‘guest’ lined up for this month we are running a review of Penne Hackforth-Jones’ biography of her great grandmother, Barbara Baynton: Between Two Worlds (1989). Over the rest of the month we will run reviews of and extracts from Baynton’s stories and her only novel, Human Toll.

Not having a ‘guest’ lined up for this month we are running a review of Penne Hackforth-Jones’ biography of her great grandmother, Barbara Baynton: Between Two Worlds (1989). Over the rest of the month we will run reviews of and extracts from Baynton’s stories and her only novel, Human Toll.

Barbara Baynton was an Australian author of the same period as Henry Lawson, that is of the Bush Realism school of the 1890s fostered by the Sydney Bulletin. There were many women writers at this time but the most popular of them, Ada Cambridge, Tasma and Rosa Praed, were of an earlier, politer, largely Melbourne-based school whose writing tended towards drawing room romances.

So Baynton, as a woman and a realist, stood out. But between Baynton and Lawson there was one major difference. Lawson’s Lone Bushman strove to support himself and to support his family, although often failing, and was pictured with humour and pathos. The women in Baynton’s fiction were hard working and resourceful but they were preyed on by the men. The Lone Bushman, to Baynton’s women, was a figure of fear.

Hackforth-Jones (PHJ from here on) attempts in this biography to set out the reasons for Baynton’s approach, successfully I think, although some of the argument is circular, ie. her understanding of Bayton’s reasoning is based largely on the stories themselves. In the Preface, PHJ writes, “Barbara Baynton left no diary and very few letters. Her articles and essays, poetry and interviews are the only evidence of her life and character apart from her three published books. Because of this, information from her friends and relatives forms the backbone of this biography.” Further, “In the early parts of the book … I have bridged gaps between known facts with the suggestions I found in her literary work.” In fact, PHJ is explicit in quite a number of places in her narrative about assuming Baynton’s fiction is autobiographical.

Add to this the reliance PHJ places on family anecdotes, and Baynton’s own wilful and frequent misstating of her antecedents, including in official documents, and you can see her account of Bayton’s early life – her childhood, first marriage and the birth of her three children – skates perilously close to faction.

Add to this the reliance PHJ places on family anecdotes, and Baynton’s own wilful and frequent misstating of her antecedents, including in official documents, and you can see her account of Bayton’s early life – her childhood, first marriage and the birth of her three children – skates perilously close to faction.

Baynton was born in Scone, NSW, in 1857, the seventh of eight children, to immigrant (English) parents. Her father, John Lawrence was a cedar cutter and timber worker. There are a number of stories about Barbara’s parents’ marriage. PHJ speculates Lawrence was another man who took both Lawrence’s wife and his name. Baynton herself used to claim her mother first married her cousin (Ewart) in England and that Lawrence was a ‘Bengal Lancer’ she met on the voyage out.

Baynton had an interrupted schooling, due both to poverty and to very poor eyesight. She was near sighted and much of the landscape was a blur. But subject to the limited resources available to her, and especially after Scone gained a public library when she was 13, she was an avid reader. In 1875 she began applying for positions as ‘governess’. The first she was offered, almost as far west as Bourke, seemed when she arrived to involve rather more contact with the men of the station than she had anticipated and she rapidly returned home. The second was closer to home, near Murrurundi, and was for the Frater family for whom she was to supervise the younger three or four of their seven children.

Let me, at this point, make two asides. Firstly, I have run into the job description ‘governess’ a number of times in reading about the Australian Bush in the C19th, including when I was researching the education of women in my own family, and it seems to mean mostly a young woman with some literacy to engage in child minding. And secondly, PHJ reports Baynton using the expression Never Never (“This is ther Never-Never – ther lars’ place Gord made”) en route to her first appointment (in 1875 or 76). Wikipedia attributed the first usage to Barcroft Boake in 1891. I have added an earlier usage, in 1884, and that I expect the expression was in general use throughout the second half of the 1800s, which this example tends to confirm.

Inevitably, Baynton married one of the older boys, Alex Frater, in 1880, and his father gave them a largely uncleared property in the Coonamble region, with a primitive timber shack and “the nearest neighbour a day’s ride away.” Alex established a home paddock to run a few cattle but was more interested in drinking and gambling than in clearing scrub and left the running of the cattle to Barbara, which was a problem as she could barely see them or make out the way home if she wandered any distance. Over the next few years they had three children, Alec, Robert and Penelope.

Briefly, Barbara engages her 18-year-old niece to help with the children, her husband runs off with the niece and gets her pregnant, and Barbara and children are destitute, living briefly with different members of her own family and dependent on Alex, and sometimes on Alex’s relatively well off mother, for support. Eventually she obtains a divorce, moves to Sydney and becomes housekeeper and then wife to the much older Dr Baynton.

Baynton began to write, drawing on the loneliness and fear she felt while isolated in the Bush, found an ally in AG Stephens, editor of the Bulletin, and a lifelong friend in her Woollahra neighbour, suffragist Rose Scott. On the basis of her husband’s position she moved rapidly up the social scale, and on his death (in 1904) invested wisely and became wealthy.

In this period Baynton apparently also ran across Miles Franklin:

Miles Franklin had just had her novel My Brilliant Career published when Barbara met her in Stephens’s office. The novel was a ‘bookful of sunlight’ to him, and he had given her a large box of chocolates as a token of his appreciation. Miles Franklin still had the box on her lap when she and Barbara sat together waiting for a tram, Miles chattering in her excitement at the success her book was having. There was no response. After a few minutes Miles began to notice how sallow Barbara’s skin was and how untidy her hair. Then Barbara smiled rather sardonically and Miles was left with the distinct impression she had sounded foolish, Barbara was envious. Talented and published girls of eighteen were not the sort of people she wanted to spend a lot of time with. She had learnt to distrust girls of eighteen, no matter how ‘fresh natural and sincere’ Stephens thought them.

PHJ positions this story in 1895, when it could only have occurred in 1902, when MF was 23. She ascribes the story to Kylie Tennant, “Miles Franklin: Feminist whose men were men”, SMH, 23 Jul 1974.

In 1902 Baynton sailed to England with her daughter and was able to have published there a collection of her short stories, Bush Studies (1902). She then commenced work on the short novel Human Toll, but without AG Stephens’ editing it was badly done and not a success. Moving backwards and forwards between London and Sydney she was in London when war (WWI) broke out. Penelope (her daughter) marries Australian journalist Henry Gullet and he and Baynton’s sons all enlist. Baynton was friends with Australian PM Billie Hughes and was both anti-women’s suffrage and pro-conscription. On the other hand her London home was open to hundreds of Australian enlisted men (not officers) on leave during the war. A classic social climber, Baynton is apparently portrayed as a cantankerous grande dame in the title role in Martin Boyd’s novel Brangane (1926).

Baynton continued to write, principally for the expatriates’ magazine the British-Australasian, and her short stories were republished, as Cobbers, with the addition of two wartime stories.

She marries a baronet, who divorces her when he can’t get at her money to support his castle in Ireland, returns to Australia, to Melbourne where her son in law builds her a fine house. And so she lives out her life in style with ‘Lady’ in front of her name, with servants, and a red Daimler.

Penne Hackforth-Jones

Barbara Baynton: Between Two Worlds

Penguin, Melbourne, 1989

164pp

see also:

TheAustralianLegend, a review of Baynton’s short story Squeaker’s Mate here

Whispering Gums, Barbara Baynton, an overview here.

ShawJonathon, another review of this biography here.

Morgan Burgess, “Barbara Baynton: celebrated colonial authoress”, an article from 2017 on the AWW blog here.

Penelope Beatrix Hackforth-Jones (5 August 1949 – 17 May 2013), a journalist as well as a much-loved actress, was the grand daughter of Sir Henry Gullett and Barbara Baynton’s daughter Penelope (Frater).

Thanks, Bill. It strikes me how many of the early writers seem to have had the time and money to write. Baynton did very well to get anywhere given her start in life, and her awareness of life’s precariousness adds a power to her prose.

I hope you enjoy the nonfiction piece I’ve chosen for Friday. I wonder how much first-hand experience she had a domestic duties. Quite a bit, I think.

Baynton only wrote when she finally achieved a comfortable marriage, and then widowhood. It’s a shame she didn’t keep going, but perhaps she had said all she wanted to about the horrors of bush life.

Miles Franklin wrote My Brilliant Career when she could get away from chores set by her mother, although reading between the lines in Cockatoos, I don’t think she had it as hard as she sometimes made out. In Cockatoos an older cousin dobs her in for going off with boys to the back paddocks where they could picnic and compare writings. I wonder who that really was. I’d be surprised if it was her sister Linda.

I have this book on my TBR, and although it is a bit suspect having been written by a relation, I do plan to read it because it clearly offers some insights into Baynton.

I enjoyed your brief discussion of the Never Never, btw, I’ve never really thought about it before.

Thanks for the link ato my overview post.

I’ve never gone back to the never never entry in Wiki though I think about it whenever I run into a reference, which I do quite often. Or perhaps I just feel that way because of the work we’ve been doing with Mrs Gunn.

Rellos are often the most motivated to write biographies. I think Hackforth Jones was close enough to be interested but sufficiently distant to be relatively unbiased.

Yes I think that’s right to a degree about Hackforth Jones but relatives will still tend to have pride in their famous forebear. JA’s family maintained some myths for a long time though they were closer to her, I admit, than PHJ was to BB.

I too am a great granddaughter of BB – Penne and I are the same age and we met at Sydney Library at times throughout BTW. My mother, Joan, was Alec Frater’s daughter and twin sister to Lexie.

Dame Leonie Kramer was the first woman to chair the ABC and a Professor of Australian literature.

Dame Leonie visited my grandmother, Lily, in around late 1960s with a view to producing a 4-part series on the life of BB. My grandmother was very upset and said she would rather wait until she died. We couldn’t work out why until my grandmother passed away in her Her early 90s and it concerned her first born.

I told Penne this and she had no idea Dame Leonie approached my grandmother.

After book published I found a couple of interesting letters that gave me a little more insight into BB.

As far as I know all greatgrandchildren were afforded an income which enabled us all to go to private schools (via income from The Law Book Company and previous director of North Broken Hill Co.). Her will was finally broken up around the 1969s.

I hope one day a series will be made of her life – what a gutsy lady and I thank her for being my great grandmother (warts and all).