by Bill Holloway

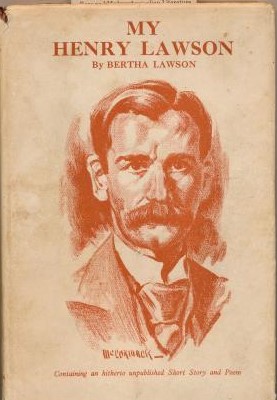

Over the next couple of weeks we’ll be looking at suffragist, first wave feminist and newspaper proprietor Louisa Lawson, but I’ve chosen to start with my review of a not very well known biography of Henry Lawson by his wife Bertha.

Over the next couple of weeks we’ll be looking at suffragist, first wave feminist and newspaper proprietor Louisa Lawson, but I’ve chosen to start with my review of a not very well known biography of Henry Lawson by his wife Bertha.

My Henry Lawson, published in 1943 and never republished as far as I can see, is a memoir of the great short story writer by his wife. Other works about Henry Lawson I read during my studies included City Bushman by Christopher Lee and Louisa by Brian Matthews. Briefly, Lee argues that the mythologising of Australian bush workers was a product of city-based writers, in particular Henry Lawson; while Louisa is an idiosyncratic account of the life of one of our great Independent Women, who also happened to be Henry’s mother. Bertha writes of her mother in law:

If there is anything in heredity, Harry’s literary talents undoubtedly came from his mother, who fifty years ago, owned and published the first women’s newspaper in Australia. It was called “the Dawn – a Journal for Australian Women.”

Lawson, then quite young and not yet a published poet, was working elsewhere at the time and “had nothing to do with it, not even as a contributor”. Later in the same chapter Bertha writes:

Louisa was a remarkable character, a very determined woman and she and her poet son could never see eye to eye. Apart they remained friendly; together they were at daggers-drawn. They had many and fierce arguments and eventually Harry left home.

Henry Lawson was born at Grenfell, NSW, in a tent, on June 17, 1867. A “birth in a mining camp … was such a novelty, that every digger visited the home to ask to see the baby and to leave generous presents.” Bertha describes Lawson’s antecedents and upbringing, and it is important in light of Lee’s argument to emphasise just how much time Lawson spent in the bush, both growing up and as a young man.

Henry Lawson was born at Grenfell, NSW, in a tent, on June 17, 1867. A “birth in a mining camp … was such a novelty, that every digger visited the home to ask to see the baby and to leave generous presents.” Bertha describes Lawson’s antecedents and upbringing, and it is important in light of Lee’s argument to emphasise just how much time Lawson spent in the bush, both growing up and as a young man.

Lawson spent some time in bush schools, though was often truant or helping his parents with work, and then his deafness, caused by illness, also intervened. Louisa had some poetry published in a local paper and Lawson, aged around 10 or 11, attempted some as well but his father objected to his “vaporisings” and they were thrown in the fire. At 14 he was working full time for his father who was a building contractor in country towns west of the Blue Mountains. His education was only resumed after Louisa left her husband and moved to Granville (Sydney) where Henry, then 16, was able to attend night school 3 nights a week. Within a year he had a poem about a shipwreck then in the papers (The Wreck of the Derry Castle) accepted by Archibald for publication in the Bulletin.

Lawson made a number of attempts to matriculate so he could go on to university, but failed, about which he was always bitter: “I was taught too little? I learnt too much/To use a pedant’s diction” (Lawson, The Uncultured Rhymer to His Cultured Critics). He drifted in and out of employment until at 19 he returned to working for his father at Mt Victoria. There “he learnt to drink and found that under the influence of liquor he forgot his shyness”. When his father died at the end of 1888, Lawson completed his contracts and returned to Sydney, drifting again, but keeping on writing, and for a while working as a columnist in Brisbane.

Meanwhile Louisa had purchased an ailing newspaper, the Republican, which had its own small printing press, and which in 1888 morphed into Dawn, a monthly newspaper for women. Louisa came into some money on her husband’s death, enabling her to enlarge her press, and within a year she was employing 10 women, including printers.

Bertha doesn’t say so, but Lawson was becoming well known. In 1892 he borrowed some money from Archibald and took off for Bourke and subsequently Hungerford in far north-west NSW looking for work. His mate Jim Grahame wrote in the Bulletin in 1925 that he and Lawson tramped around the country west of Bourke working as rouseabouts (picking up fleeces, not shearing as is sometimes reported) for six months, before Lawson returned to Sydney by train as a drover with sheep going to the abattoirs at Homebush.

In 1895 Bertha was an 18 yo nurse from Bairnsdale, Vic, in Sydney visiting her mother. A friend introduced her to Lawson who became very persistent in pursuing her and they were soon planning to get married. By this time he had two books of short stories and poetry to his credit and a third, In the Days When the World was Wide, was with the printers. The future was looking rosy. After a couple of hiccups, Bertha’s mother gave her consent and the two were married on April 15, 1896.

In her description of a rowing excursion on Middle Harbour we are given a privileged view into their lives and Lawson’s writing:

Harry took pencil and paper, and while I sat and sewed, or rowed slowly, he wrote verses, chanting them softly to himself, to get the beat and rhythm. This was different from when Harry wrote verse at home, for then he would dictate it to me in that sing-song way of his, and after I had written it down, while he paced to and fro, he would correct it and read it to me.

With money in his pocket, an advance on his book, Lawson was restless and so they sailed for WA where Lawson hoped to become a gold miner, though as it happened they never made it past a camp on the hill near the cemetery in East Perth. When their money was about to run out Bertha engineered a return to Sydney. We get a glimpse of how famous Lawson was becoming:

… in Melbourne, the pressmen came down to interview us; and although we were travelling in the steerage, the captain allowed us to use the saloon, for Harry to entertain the press. It was the grand finale to our tour, and we landed in Sydney with two shillings in the exchequer …

In Sydney Lawson’s drinking mates were a problem, and with an introduction to the Premier, they moved on again, to New Zealand. A job was found for Lawson, as the teacher at an isolated Maori school where Bertha conspired with the locals to make it difficult for Lawson to get to the ‘bright lights’ of Kaikoura 12 miles away on the coast. Here she says, Lawson did some of his best work, all of Joe Wilson and His Mates, a play, and some poetry, including Written Afterwards in which he jokes about the restrictions imposed on him by marriage.

At the beginning of 1898 they returned to Wellington where their son, Jim was born and on to Sydney, where Lawson freelanced for a while till he found work as a clerk with the Government Statistician and gave up the grog. Despite his boss telling him he only had to show up during working hours and he could write what he liked, this lasted just one week!

Another book came out, there was another advance to spend, and another baby, Bertha (b. Feb 1900). Lawson was getting good reviews in Britain, the State Governor offered to pay his passage, and soon the family were on the move again (famously taking with them the ms for Miles Franklin’s My Brilliant Career, which Lawson passed on to his publishers Blackwoods in Edinburgh).

He had become one of the literary lions of London. A dinner had been given to welcome him, at which the leading literary men were guests. The world was at Harry’s feet…

Lawson however made little attempt to take advantage of the opportunities opening up for him. And after two years on the wagon, on arrival in London he started drinking again. Friends had found housing for them, but “with all this appreciation we still had not enough money to buy food”. Mary Gilmour, her husband and child came to stay (after the failure of New Australia). “We were all in deep financial difficulties”. Then Harry got an advance from Blackwoods and Bertha “lost no time buying passages for myself and the children for Australia”. Lawson followed soon after. Anne Brooksbank fictionalizes this period, and postulates a romance between Lawson and Gilmore, in her novel All My Love (1991).

They met up again in Colombo but by the time they were back in Australia the marriage was very nearly at an end. Bertha stayed in Melbourne for six weeks, while Henry went on to Sydney; they lived together for a while in Manly, but first Henry, then Bertha, was hospitalised for long periods; their furniture was seized for arrears of rent; a third baby died at birth.

Bertha found employment as a travelling saleswoman for Stuart & Co., booksellers while Lawson took lodgings, “it was useless taking up house again as he was quite penniless and the children had to be provided for.”

He had his happy times and I think those periods were usually associated with absolute freedom from responsibility and full expression of his genius. He hated to be tied down.

In this period, immediately before the Great War, Lawson had published a prose volume The Rising of the Court and a book of verses Skyline Riders. For a while during the War, the government gave him make-work, writing advertising for the Leeton irrigation area.

Bertha goes on to analyse Lawson’s writing, his connections to the working class, where she and he fit into his stories, particularly the Joe Wilson stories, and his links to the Australian ‘Bohemians’. Lawson died in 1922, of a cerebral haemorrhage. He was given a State Funeral and according to Bertha, was buried in the grave that had been prepared for Henry Kendall.

This excellent little book ends with a previously unpublished Lawson short story, A Wet Camp.

Bertha Lawson

My Henry Lawson

Frank Johnson, Sydney, 1943

(the drawing reproduced on the cover is signed McCormack)

Related reviews:

Brian Matthews, Louisa (1987) The Australian Legend

Kerrie Davies, A Wife’s Heart: The Untold Story of Bertha and Henry Lawson (2017) The Resident Judge

Anne Brooksbank, All My Love (1991) The Australian Legend

I really appreciate how a personal memoir like this adds to our understanding of a key writer’s nature and work. Along these lines, but different, I really enjoyed Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Bronte; I approached it expecting a traditional biography but it felt like we were sitting around the table with Gaskell spilling the tea.

I have owned Gaskell’s Charlotte Bronte for many years. It really is time I read it!

We know Henry Lawson as our most famous writer of bush stories and ballads, and as a notorious drunk, so it is interesting to get the story behind this public image from the woman who knew him best.