by Elizabeth Lhuede

Another in our series of posts on works published in 1924 (or authors who died in 1924).

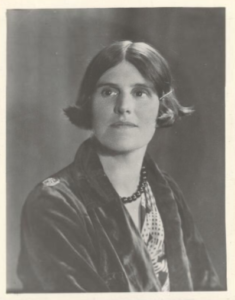

Melbourne writer Doris Boake Kerr (1889-1944), who published under the pseudonym of “Capel Boake”, is already known to AWW readers; Whispering Gums, aka Sue T, featured her in 2022. In that essay, Sue concluded with the note, “Boake is clearly worth checking out”. As Boake published several pieces in 1924, I’ve chosen to feature her work as part of our series on authors who published work one hundred years ago.

Melbourne writer Doris Boake Kerr (1889-1944), who published under the pseudonym of “Capel Boake”, is already known to AWW readers; Whispering Gums, aka Sue T, featured her in 2022. In that essay, Sue concluded with the note, “Boake is clearly worth checking out”. As Boake published several pieces in 1924, I’ve chosen to feature her work as part of our series on authors who published work one hundred years ago.

In 1917, after the publication of Boake’s first novel, Painted Clay, a reviewer in The Argus declared:

[Boake] is one of those who seeks for the meaning and purpose in life, and her work contrasts strikingly with the cheerful superficiality and shallowness of the potboilers of some highly popular Australian authoresses. It is safe to predict for this thoughtful writer a future in the literary world.

Seven years after the reviewer’s prediction, was she on track to achieve her early potential?

In 1924 Boake published three poems and four prose pieces. Most appeared in The Herald, with one poem in The Australasian and a short story in The Weekly Times. Among the prose pieces, three were short stories; the fourth, written in the first person, appears to have been drawn from real life, but reads like fiction to me.

First to appear was the short story, The Green God. It features a “modern girl”, like the one Lilian Pyke cast a critical eye over in the short story Sue featured last week. Boake’s modern girl is a newly married woman who, instead of paying the household electric and gas bills, purchases a figure from an antique store, then tells her husband she forgot about the bills. The story is a glimpse into middle-class, urban life; the conflict between husband and wife is a clash of values, aesthetic versus practical, and is humorously and deftly drawn. Boake’s portrayal of the flawed heroine is anti-sentimental, however the story is no serious study of human nature.

The Bargain, appearing a month later, is a longer and more ambitious effort, portraying characters whose lives have been impacted by the First World War. Here Boake creates another “modern woman”, the jaded ex-lover of a man who never came back from the war, and the story centres around her intervention in the lives of a young rural couple facing financial ruin. Both women in the story, the young wife and the ex-lover, are shown to be susceptible to moral compromise, although their decisions are arguably for the greater good. In this aspect, the story hints at Boake’s seeking for “meaning and purpose in life” that the reviewer detected in Painted Clay.

The third short story, A touch of the sun, features a mixed-race heroine, dealing with an issue that might’ve been considered daring at the time of publication. Boake appears sympathetic to her character, whose desire to connect with her ancestral land, along with her struggle against this impulse, forms the story’s core. The fact that the woman not only resists the desired connection, but also is ultimately rescued from it, suggests an internalised racism which is never really critiqued. Rather, her mixed-race ethnicity is exoticised, exploited to create the story’s air of mystery, even mystique. It makes for uncomfortable reading for a contemporary reader, and reminds us of the racist historical context of the story, the time of the White Australia policy, and the difficulties faced by those of mixed race.

Boake’s fourth prose piece to appear in 1924 was Tiny feet. Set in a Melbourne boarding house, it employs the genre of the tall tale, an anecdote told by one guest for the amusement of others. The narrator, who might well have been one of those “modern women”, comes across as slightly jaded, but not above revealing her human frailties. “We were all secretly bored,” the narrator admits, when the taleteller, an Englishman and ex-adventurer, insists on recounting his story. This admission has a conspiratorial quality, as if the narrator is daring the reader to judge for herself whether the man’s story deserves our attention. What follows is a well-told, short tale of the Englishman’s encounter with an impoverished White Russian in a small Russian town after the Revolution. It’s engaging, but more spy-thriller, with a dash of romance, than a deep interrogation of the human psyche; a story, I’d suggest, not so very far away in tone from the superficial pot-boilers the Painted Clay reviewer disparaged.

So what of the poems Boake published in 1924?

Boake had three poems published that year, The Grey Street and Quiet Things in June, and The Prisoner, in October. The last is a plaintive address to a caged bird, an evocation of the yearning of a wild creature for a life it will never know:

Prisoner, behind your woven bars,

Your bright eyes fixed on the patch of sky…

Do you see the morning mists unfold

The green and gentle Dandenongs?

The deep dark gullies, the waters cool;

Is it for these your spirit longs?

Is it just me, or does this poem suggest the poem’s persona identifies with the caged bird and its longing?

In “Quiet Things”, with its repeated lines beginning, “I love… I love…”, Boake celebrates the small joys of life: “the calm of autumn”, “softly drifting leaves”, “the grey and glimmering dusky”, the “lighted windows bright” of “little houses on the hill”, and “little gardens trimmed neat”. It ends with the stanza:

I love the quiet sounds of life––

The fire crackling on the heart;

The clear, sweet sound of evening bells;

The cricket on the garden path.

And, oh, I love, so faintly heard,

The shrill, wild cry of a homing bird.

In this last line, as in “The Prisoner”, I detect more than a little human longing. The oxymoronic contrast of the “wild cry” with “homing bird” suggests a tension between the known, the familiar, and the call of something wilder. For me, this tension lifts the poem above what contemporary critics might have described as mere “versifying”.

In “The Grey Street”, Boake offers a different glimpse of urban life, one that evokes the conditions from which such a longing to escape might arise. The poem’s repetition, its almost doggerel beat, creates a sense of monotony and inevitability of the down-trodden life. The persona not only has compassion for such an existence, but also intimate knowledge of the feelings identified, acknowledging a shared experience of life’s limitations and disappointments. It’s a poem that demonstrates Boake’s darker, more serious side and is featured in full below.

The Grey Street by Capel Boake

I never walk the grey street; the long, lonely grey street.

Where dust lies thick on every house, on garden and on tree;

But as I tread the grey street, the long, unlovely grey street,

A ghostly hand; a lonely hand, keeps step for step with me.

I hear them in the grey street; they call me to the grey street;

I hear their slow and shambling feet, their broken, desperate cries.

They haunt me in the grey street; the cruel, heartless grey street,

Those lonely ones with empty hands and hopeless, dreadful eyes.

In houses in the grey street; unlovely as the grey street,

In dingy rooms with broken blinds, an up the creaking stair,

Their prison is the grey street; they’re caught within the grey street;

And who shall know, and who shall heed, their longing, and despair?

For only to the grey street, the barren, empty, grey street,

Come those whom life has torn and rent, the hopeless and bereft.

They’re lost within the grey street; they’re victims to the grey street;

And of the gifts that life can give, but life itself is left.

I would forget the grey street, for I fear the haunted grey street;

I would forget those lonely lives, but they call to me again;

And in dreams I tread the grey street; for I know the dreary grey street;

I know its dank and rotting homes, its hopelessness and pain.

~

References

Capel Boake, A touch of the sun, The Herald, 6 Sep 1924: 13, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/243885958 accessed 27/04/2024.

–– The Bargain, The Weekly Times, 28 June 1924: 47, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/222807286 accessed 27/04/2024

–– The Green God, The Herald, 24 May 1924: 15, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/246160875 accessed 27/04/2024

–– The Grey Street, The Herald, 21 Jun 1924: 15, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/246172095 accessed 27/04/2024

–– The Prisoner, The Australasian, 11 Oct 1924: 58, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/140762522 accessed 27/04/2024

–– Quiet Things, The Herald, 28 Jun 1924: 13, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/246158372 accessed 27/04/2024

–– Tiny Feet, The Herald, 25 Oct 1924: 1, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/244851614 accessed 27/04/2024

[Unknown reviewer], “Fiction of the day: an Australian novel”, The Argus, 15 Jun 1917: 5; https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/1625683 accessed 27/04/2024

~

Elizabeth Lhuede has a PhD in Australian Poetry from Macquarie University. In 2012, she instigated the Australian Women Writers Challenge, as a contribution to overcoming gender bias in the reviewing of works by Australian women. More recently she has focused on bringing to light the life and works of forgotten Australian women writers.

Elizabeth Lhuede has a PhD in Australian Poetry from Macquarie University. In 2012, she instigated the Australian Women Writers Challenge, as a contribution to overcoming gender bias in the reviewing of works by Australian women. More recently she has focused on bringing to light the life and works of forgotten Australian women writers.

You’ve started me thinking about what the expression ‘modern woman’ meant in the 1920s and also what its relation to modernism might be. Searching on ‘modern woman 1920’ brings up some interesting ideas.

That’s great, Bill. I’ll be interested to know what you come up with.

Thank you for posting Elizabeth. Yes! What is a modern woman. I’ll have to read the first story. The poem in full is so depressing and surely the tone of it suggests she experienced some sort of depression in her life. I am reading the British Magazine The Bystander for 1924 and in April the Australian writer Winifred James published a novel Out of the Shadows. I noticed she’s not on the list. Perhaps because she was living in London and not submitting stories here?

I think you could be right, Debbie. The poem is very bleak, isn’t it?

I’ll have to look up Winifred James. Is Out of the Shadows available online?

Good question Bill. I guess the 1920s was one of those cusp times when things seemed on the move, only to be brought down by the Depression and then War? So, a good moment when women might have been breaking chains but the breaking was halted? Are you planning to post on what you found about the modern woman in the 1920s?

Really enjoyed this post Elizabeth. I liked your trajectory ending the The Grey Street.