by Janine Rizzetti

Vida Goldstein (1869-1949), the leader of the Suffragist movement in Victoria at the turn of the last century, was a woman of significance both in Australia and in the wider world. We have reprised here Dr Rizzetti’s review of Bomford’s biography from 2017.

Vida Goldstein (1869-1949), the leader of the Suffragist movement in Victoria at the turn of the last century, was a woman of significance both in Australia and in the wider world. We have reprised here Dr Rizzetti’s review of Bomford’s biography from 2017.

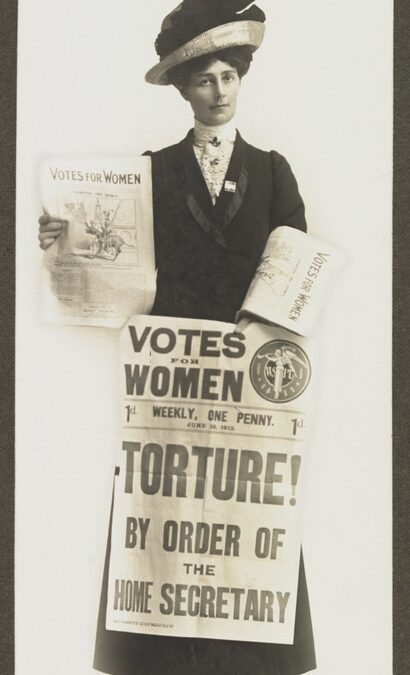

Vida Goldstein is remembered as a suffragist, social reformer and pacifist. The picture on the front Bomford’s biography encapsulates what we tend to think of as the quintessential first-wave feminist, in her Edwardian clothing and earnest demeanour. It’s a photograph of Vida Goldstein, taken by T. Humphrey and Co Photographers, holding a placard dated 28 June 1912 about the English suffragist campaign. At this time, Vida Goldstein would stand in the Melbourne streets – a shocking sight- posters pinned to her skirt, selling the newspaper ‘Votes for Women’ and her own ‘Woman Voter’ publication.

Vida Goldstein’s internationalism was just one aspect of her life that Janette Bomford highlights for us in this biography. At a time when women elsewhere in the Empire were still fighting for the right to vote, New Zealand and Australian women (who received the vote in 1893 and 1902 respectively) were feted in suffragist circles as an example of the new world to come. She travelled to America as Australian delegate to the International Woman Suffrage Conference Fed 1902, aged 32 and was the delegate from the NSW chapter of National Council of Women to the Conference of International Council of Women, held immediately afterwards. She was elected Secretary to the International Woman Suffrage Committee, serving alongside the 82 year old American feminist Susan B. Anthony who was President. While in America she undertook research into youth justice and criminology, two interests that she was to pursue throughout her life.

Vida Goldstein’s internationalism was just one aspect of her life that Janette Bomford highlights for us in this biography. At a time when women elsewhere in the Empire were still fighting for the right to vote, New Zealand and Australian women (who received the vote in 1893 and 1902 respectively) were feted in suffragist circles as an example of the new world to come. She travelled to America as Australian delegate to the International Woman Suffrage Conference Fed 1902, aged 32 and was the delegate from the NSW chapter of National Council of Women to the Conference of International Council of Women, held immediately afterwards. She was elected Secretary to the International Woman Suffrage Committee, serving alongside the 82 year old American feminist Susan B. Anthony who was President. While in America she undertook research into youth justice and criminology, two interests that she was to pursue throughout her life.

Nearly ten years later Vida Goldstein travelled to England in 1911 as a guest of the Pankhursts and the Womens Social and Political Union, spoke to 10,000 people in the Albert Hall and organized a contingent of ‘overseas’ women in the Great Suffrage Procession in June 1911. As Bomford points out, her contact with the most eminent suffrage workers in the United States and Britain brought her a sense of sisterhood and camaraderie that she never quite felt in Australia (p.219)

Goldstein’s commitment to women as voters and politicians in their own right dominated much of her public career. Her mother, Isabella, was from the Scottish/Australian squattocracy of Victoria’s Western District. Mr Goldstein was in business, in rural Victoria and then in Melbourne and was able to send Vida to PLC, Melbourne’s principal girls’ school. Both parents were involved in charities and Isabella was in the Victorian Womens Suffrage Society from 1884, and, with Annette Bear-Crawford, was integral in obtaining funding for Melbourne’s first women’s hospital, the Queen Victoria, in 1897.

Initially, Vida and her sisters supported themselves by running a co-ed preparatory school. But Vida quickly discovered an aptitude for organizing and speaking. She cut her teeth as a committee member and organizer with the United Council for Women’s Suffrage and the Women’s Federal Political Association, and by the time Bear-Crawford died unexpectedly in 1899, Vida Goldstein was undisputed leader of the radical women’s movement in Victoria.

It was the WFPA, later renamed the Women’s Political Association, that proclaimed itself to be unaligned to any political party, a stance which probably cost Goldstein electoral support in her three attempts to stand for the Senate as a Victorian representative, and two attempts at the House of Representatives seat of Kooyong. She was the first woman in the Empire to stand for political office, even though she was never successful. During the election held between the two Conscription referenda in 1916 and 1917, she was accused (with good reason) of splitting the anti-conscription vote, even though she was herself an ardent pacifist.

Her commitment to pacifism split the Women’s Political Association in the early years of the war, when there was strong support generally for Australia’s involvement. It led her to split with the Pankhursts in England, despite her involvement in the suffrage campaign there less than five years earlier. It brought her into the spotlight of public attention as she campaigned with the Women’s Peace Army, of which she was a founding and highly visible member (I’m sure that her selection of the same initials as the Women’s Political Association was no accident- and it made taking notes on this book a nightmare!) She was mainstream middle-class, stylishly dressed and a very capable public speaker, and she spearheaded the ‘No’ case during the Conscription referendum campaigns.

In many ways, the different aspects of her political life often clashed up against each other: the support for militant suffragism and yet strong pacifism; her determination not to align herself with a political party, even though it hurt the left of politics to which she more naturally leaned. As Bomford explains, she was a strong but inflexible character. Her parents had given her a good education, first at home with a very capable governess, and then at PLC. However, in a foretaste of what was to come, the family split over the issue of women’s suffrage when her parents publicly took diametrically opposed views. Through her parents, she became involved in the Charity Organisation Society of which they were founding members, which took a ‘case study’ and causal approach to poverty, and championed dignity in work rather than handouts to ‘deserving’ cases as practised by the Ladies Benevolent Society. It was to her family that she looked for emotional sustenance, living with her sisters and brother-in-law in South Yarra for the last thirty years of her life. Despite her name (which she always pronounced with ‘eye’ in both her first and surnames) she was not Jewish. Her religious and spiritual life was nurtured through Rev Charles Strong’s ministry first at Scots Presbyterian and then the Australia Church, and increasingly through Christian Science, to which she devoted her passion post WWI.

As Bomford explains, with Vida Goldstein there is no cache of personal papers for the biographer to mine. Fortunately, her correspondents often did keep her letters, most particularly her friend Stella Miles Franklin. As a result, Bomford has had to rely on newspaper reports, Vida’s own writing in her various newspapers and speeches, and the reports of the government censors and security organizations. The constraints of material have constrained Bomford to write mainly of Goldstein as a public figure. Nonetheless, I think that Bomford does a good job in giving an internal logic and unity to Goldstein’s politics, even though her inflexibility so often worked against the causes she believed in, and cost her many allies.

This is an academic text, with quite a few initials for organizations, which is just as much part of the territory in discussing political activism today as it was at the turn of the twentieth century. It takes a strictly chronological approach, and most of the character analysis takes place in the ‘Afterword’ that closes the book. It is probably not widely available today, given the ferocious culling of texts in libraries and short shelf-life of books in bookshops, but Vida herself has taken on even more prominence with the recent interest in the conscription debates of WWI and the toxic politics around Julia Gillard’s Prime Ministership. ABC’s Hindsight program had an excellent episode about her in 2009 which is available as podcast and transcript here . Claire Wright also discusses Vida on a Podcast from La Trobe University’s Biography series available at https://player.fm/series/biography/vida-goldstein (the text is similar to Wright’s entry on Goldstein at the Encyclopedia of Women and Leadership in Twentieth Century Australia). She also wrote a very good essay ‘Birth of a Nation?’ in Griffith Review 51 available here.

.

Janette M Bomford,

That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman: Vida Goldstein

Melbourne University Press, 1993

226pp & notes

Janine Rizzetti is an historian, and former History Editor of this site, who blogs at The Resident Judge of Port Phillip

see also: reviews of Jaqueline Kent’s Vida: A Woman for Our Time (2020) at The Resident Judge, and The Australian Legend.