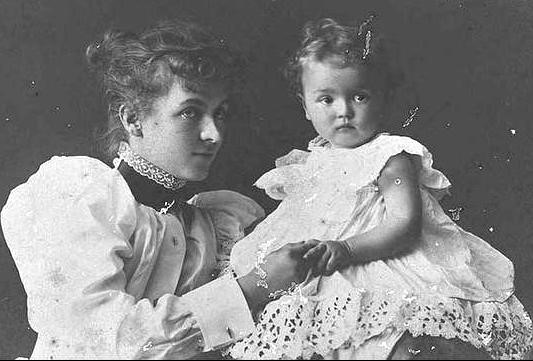

“The girlie loves her bath but the minute I take her out she screams and screams till by the time I have her dressed she has me reduced to tears also. Then she smiles complacently as if that were her sole object and falls into a lovely sleep. She and I both had an afternoon sleep and woke much restored” (Turner, 1979: 174).

Ethel Turner’s diary entry for 25th March 1898—small as it is–humorously and honestly captures the wiles of her capricious month-old daughter, Jean, as she learns to grapple with the novelty of motherhood alongside her husband, Herbert Curlewis. Ethel’s ability to describe children candidly is perhaps what most admire about her literary career that spanned six decades, embedding her name and her stories into Australia’s literary conscience. Born in 1873, Ethel is a much-beloved and brilliant Australian children’s author known for Seven Little Australians (1894), The Little Larrikin (1896), Three Little Maids (1900) and the wartime Cub Trilogy (1915-1919), among other works. Though much can be said of Ethel’s 34 volume oeuvre, a snapshot of her life and works—from her first and remarkably successful novel, Seven Little Australians (SLA) in 1894, to her almost forgotten novel, Mother’s Little Girl (MLG) in 1904 —reveals the various ways in which Ethel explored her ever-changing family relationships within ten years.

Seven Little Australians narrates the adventures of the seven Woolcot children: Meg, Pip, Judy, Nellie, Bunty, Baby, and the half-brother, General at their family home, ‘Misrule’. “Not one of the seven is really good” warns the narrator, but Judy, the bright-eyed, thirteen-year-old girl was undoubtedly “the worst of the seven, probably because she was the cleverest” (SLA: 1, 6). The children, under Judy’s leadership, work up comical mischief as they strive to fret and please their twice-married father, Captain Woolcot, by turns. Ethel’s first novel is certainly a reflection of her childhood, that sweet and passionate innocence in which Ethel intentionally enveloped herself. In 1892, she declared: “I have been very young I think for 20, most girls of 14 are older. Some things are bitterly disappointing. I don’t half understand them, I don’t want to either” (31 May 1892; Turner, 1979: 80). Ethel’s reluctance to let go of her childhood can be seen in the siblings’ reluctance to let go of Judy in Seven Little Australians when she is packed off to a boarding school.

Moreover, the novel hinges on the tumultuous parent-child relationship between Captain Woolcot and Judy—the daughter who “always mystified him” (SLA: 25). As he watches her mow the lawn, he reflects on her nature:

“That restless fire of hers that shone out of her dancing eyes, and glowed scarlet on her cheeks in excitement, and lent amazing energy and activity to her young, lithe body, would either make a noble, daring brilliant woman of her, or else she would be shipwrecked on rocks the others would never come to, and it would flame up higher and higher and consume her” (SLA: 25).

But Judy never lives to fulfil either of these expectations. It is Judy the Captain packs off to a boarding school at Katoomba as punishment for openly challenging his paternal responsibilities; it is Judy he sends urgently to recover at Yarrahapinni with her siblings to urge her recovery from a near-fatal inflamed lung after she escapes from boarding school; and, finally, it is the heroic Judy he buries at Yarrahapinni after she dies trying to save the General from a falling gum tree in his absence. And, yet, Judy’s death still cannot redeem Captain Woolcot at the conclusion of the novel. The narrator remarks that though “Judy’s death made his six living children clearer to his heart […] he showed his affection very little more” (SLA: 206).

At the time in which Ethel was writing Seven Little Australians, she was living at home with her mother, Sarah, and second step-father, Charles Cope. And so, it is very likely that the agitated relationship between Captain Woolcot and Judy reflects Mr Cope’s own inability to deal with the industrious and free-spirited natures of his step-daughters Ethel, Lilian and Rose. Indeed, Charles is described as “a man with a violent temper and disposition to tyranny” who unwittingly believed “that his two elder step-daughters would accept the limitations of a life of leisure” provided by the son of a landed gentry, shipping Rose off to a boarding school in Bowral and, as is conjectured, refusing Lilian and Ethel entry into university after finishing their schooling at Sydney Girls High School (Yarwood, 1994: 18, 23). Thus, in Seven Little Australians, Judy’s death haunts readers to this day as an unjustified death; in the same way, I believe Ethel tried to express, a child’s innocence, hopes and expectations can be unjustly destroyed by the mishandling of a parent-figure.

However, Mother’s Little Girl—written ten years after Ethel’s induction into literary fame—changes the perspective significantly, from a child’s point-of view to a parent’s. Though it has a much happier ending, it is a story that has visibly removed the innocent bubble in which Ethel contented herself to belong. One of the most significant changes in Ethel’s life between 1894 and 1904, is her marriage to Herbert Curlewis, an incredible event considering Ethel’s aversion to marriage. Unfortunately, her mother and stepfather had an unhealthy relationship. As A.T. Yarwood, Ethel’s biographer, writes, “marriage was the last thing on Ethel’s mind. She had a career to set in motion and […] the quarrels of Charles and Sarah Cope discouraged emulation” (Yarwood, 1994: 33). But thanks to Herbert’s patience, Ethel ultimately prepares herself for marriage—all its glories and grim (mostly financial) realities—in April 1896.

Accordingly, Mother’s Little Girl straightforwardly, if not onerously, acknowledges the sacrifices that must be made by the Waller family to overcome their state of unhappy poverty. It is exactly at Ellie and Ted Waller’s rock bottom that the novel begins: the bills piling up; Ted out of work for months, the arrival of their sixth child, another toddler seriously injured and Ellie on the verge of illness. The narrator quickly asserts the alarming crises at which the Waller family finds itself: “What unspeakable horror if she should be ill—really ill! They could only afford the nurse for a fortnight [… and] Every one [sic] needed her back at her post”—especially her children, all under ten years of age: Ruth, Walter, Bonnie, Winnie, Brian and, now, their newest baby girl (MLG: 15). The clouds continue to gather until Alice—Ellie’s wealthy and childless sister—sends a note for £100 to buy the newest addition to the Waller Family. Though reluctant at first, the Wallers must concede to make ends meet, though they mourn their decision for years. Sylvia, as Alice names her niece-daughter, grows up in the lap of luxury loved by her parents, including her uncle-father Wilf and his brothers Angus and Robert. Sylvia’s presence ultimately softens the adults, teaching them to love each other and reconcile.

In much the same way, Ethel’s life had changed dramatically since writing Seven Little Australians, and she was no longer a child who was subject to the whim of her parents, but the crux upon which a large family depended. One crucial event was Lilian’s marriage to a dentist, Frederick Thompson in 1898. The Australian Dictionary of Biography explains that Ethel often supported her sister financially as Frederick was often unemployed. Ethel’s only recorded diary entry for 1904 reads: “Worried over the O’Brien’s troubles and Lil’s troubles and H’s brother’s troubles till I could only see one solution—I must write a play that will bring at least £10,000” (undated; Turner, 1979: 216) And it is perhaps this changed, fraternal relationship that Mother’s Little Girl nostalgically explores. After five years of separation, Alice and Sylvia plan a trip to Ellie’s cottage to meet all the ‘cousins’, but in a matter of moments the reunion of ‘cousins’ is overshadowed by the sisters, Ellie and Alice, running into each other’s arms as “it seemed but yesterday that they were plaiting each other’s hair at boarding school, […] and going under punishment together for having a novel by Ouida in their trunk” (MLG: 227).

But for all the nostalgia of a lost youth and the realities of an inverted dependency, Ethel also celebrated notable events through the novel. Including, of course, the birth of her daughter, Jean Curlewis, in 1898, and son, Adrian Curlewis, in 1901; as well as moving the small and happy family into their dream home, Avenel, in 1903. “‘My ideal home, my sacred place,” writes Ellie to her sister,

“‘is hidden among loving and guarding trees, approached by winding paths and slopes of grass where I can wander freely in the sunshine with my boys and girls and listen to their young hopes and fears. And in the moonlight, heart to heart to the husband who is still my lover’” (MLG: 111-112).

At the conclusion of Mother’s Little Girl Alice realises she could never take the place of Ellie and allows Sylvia to return to her large and boisterous family. As opposed to the child-like voice that pleads for mercy in Seven Little Australians, a decade sees a maturing Ethel describe the beautiful challenges that arrive when a child enters a colourful family and strengthens the family bonds already in existence. Despite these two contrasting perspectives, it is clear that children were the ineffable centre of Ethel’s life. And, upon the death of her beloved daughter Jean in 1930, Ethel never wrote again in the twenty-five years that remained of her life.

References:

Turner, Ethel. 1894. Seven Little Australians (2012). Melbourne, Vic: Viking an imprint of Penguin Books.

Turner, Ethel. 1904. Mother’s Little Girl. London and Melbourne: Ward, Lock & Co. Ltd.

Turner, Ethel. 1979. The Diaries of Ethel Turner compiled by Philippa Poole. Sydney, NSW: Lansdowne Press.

Yarwood, A.T. 1994. From A Chair in the Sun: The Life of Ethel Turner. Ringwood, Victoria: Viking Penguin Group.

About Narelle Ontivero: Narelle is a doctoral candidate at Western Sydney University in the Writing and Society Research Centre. Her current research explores the relationship between space, gender and identity in the works of Tasma, Rosa Praed and Ada Cambridge.

Thanks for an interesting perspective on a remarkable woman and writer. I wonder though how many children now read her books? I hope some do.

Thanks so much Narelle. I hunted out all four of Jean Curlewis’s books. You can read my reviews on Goodreads. Her books are very enjoyable to read and you can’t help but wonder what she would have gone on to write if she had lived for a reasonable length of time.

Hi there

I own Exeter House in Nt Victoria Blue Mountains which has been touted as the school in the book Seven Little Australians. We have done our research and refute this information. Are you able to confirm for me if Exter House was or was not the boarding school

Thanks

Ann

No, I have no way of confirming that. I’m not even sure how you would find out. It could just be that the author made it up – it is a work of fiction afterall. Many authors have used existing houses and re-imagined them as schools and other institutions.